Preface from the book "Maps of Meaning" by Jordan Peterson

Something we cannot see protects us from something we do not understand. The thing we cannot see is culture, in its intrapsychic or internal manifestation. The thing we do not understand is the chaos that gave rise to culture. If the structure of culture is disrupted, unwittingly, chaos returns. We will do anything-anything-to defend ourselves against that return. “The very fact that a general problem has gripped and assimilated the whole of a person is a guarantee that the speaker has really experienced it, and perhaps gained something from his sufferings. He will then reflect the problem for us in his personal life and thereby show us a truth.”: Jung, C.G. (1978a), p. 78; also: Although seemingly paradoxical, the person who takes upon himself, the people's humiliation, is fit to rule; and he is fit to lead, who takes the country's disasters upon himself. (Lao-Tzu, 1984c) I was raised under the protective auspices, so to speak, of the Christian church. This does not mean that my family was explicitly religious. I attended conservative Protestant services during childhood with my mother, but she was not a dogmatic or authoritarian believer, and we never discussed religious issues at home. My father appeared essentially agnostic, at least in the traditional sense. He refused to even set foot in a church, except during weddings and funerals. Nonetheless, the historical remnants of Christian morality permeated our household, conditioning our expectations and interpersonal responses, in the most intimate of manners. When I grew up, after all, most people still attended church; furthermore, all the rules and expectations that made up middle-class society were Judeo-Christian in nature. Even the increasing number of those who could not tolerate formal ritual and belief still implicitly accepted—still acted out—the rules that made up the Christian game. When I was twelve or so my mother enrolled me in confirmation classes, which served as introduction to adult membership in the church. I did not like attending. I did not like the attitude of my overtly religious classmates (who were few in number) and did not desire their lack of social standing. I did not like the school-like atmosphere of the confirmation classes. More importantly, however, I could not swallow what I was being taught. I asked the minister, at one point, how he reconciled the story of Genesis with the creation theories of modern science. He had not undertaken such a reconciliation; furthermore, he seemed more convinced, in his heart, of the evolutionary viewpoint. I was looking for an excuse to leave, anyway, and that was the last straw. Religion was for the ignorant, weak and superstitious. I stopped attending church and joined the modern world. Although I had grown up in a Christian environment—and had a successful and happy childhood, in at least partial consequence—I was more than willing to throw aside the structure that had fostered me. No one really opposed my rebellious efforts, either, inchurch or at home—in part because those who were deeply religious (or who might have wanted to be) had no intellectually acceptable counter-arguments at their disposal. After all, many of the basic tenets of Christian belief were incomprehensible, if not clearly absurd. The virgin birth was an impossibility; likewise, the notion that someone could rise from the dead. Did my act of rebellion precipitate a familial or a social crisis? No. My actions were so predictable, in a sense, that they upset no one, with the exception of my mother (and even she was soon resigned to the inevitable). The other members of the church—my “community”—had become absolutely habituated to the increasingly more frequent act of defection, and did not even notice. Did my act of rebellion upset me, personally? Only in a manner I was not able to perceive, until many years later. I developed a premature concern with large-scale political and social issues, at about the same time I quit attending church. Why were some countries, some people, rich, happy and successful, while others were doomed to misery? Why were the forces of NATO and the Soviet Union continually at each other's throats? How was it possible for people to act the way the Nazis had during World War II? Underlying these specific considerations was a broader, but at the time ill- conceptualized question: how did evil—particularly group-fostered evil—come to play its role in the world? I abandoned the traditions that supported me, at about the same time I left childhood. This meant that I had no broader socially constructed “philosophy” at hand to aid my understanding as I became aware of the existential problems that accompany maturity. The final consequences of that lack took years to become fully manifest. In the meantime, however, my nascent concern with questions of moral justice found immediate resolution. I started working as a volunteer for a mildly socialist political party, and adopted the party line. Economic injustice was at the root of all evil, as far as I was concerned. Such injustice could be rectified, as a consequence of the rearrangement of social organizations. I could play a part in that admirable revolution, carrying out my ideological beliefs. Doubt vanished; my role was clear. Looking back, I am amazed at how stereotypical my actions—reactions—really were. I could not rationally accept the premises of religion as I understood them. I turned, in consequence, to dreams of political utopia, and personal power. The same ideological trap caught millions of others, in recent centuries. When I was seventeen I left the town I grew up in. I moved nearby and attended a small college, which offered the first two years of undergraduate education. I involved myself there in university politics—which were more or less left wing at that time—and was elected to the college board of governors. The board was composed of politically and ideologically conservative people: lawyers, doctors, and businessmen. They were all well (or at least practically) educated, pragmatic, confident, outspoken; they had all accomplished something worthwhile and difficult. I could not help but admire them, even though I did not share their political stance. I found the fact of my admiration unsettling. I had attended several left-wing party congresses, as a student politician and active party worker. I hoped to emulate the socialist leaders. The left had a long and honorable history in Canada, and attracted some truly competent and caring people. However, I could not generate much respect for the numerous low-level party activists I encountered at these meetings. They seemed to live to complain. They had no career, frequently, andno family, no completed education—nothing but ideology. They were peevish, irritable, and little, in every sense of the word. I was faced, in consequence, with the mirror image of the problem I encountered on the college board: I did not admire many of the individuals who believed the same things I did. This additional complication furthered my existential confusion. My college roommate, an insightful cynic, expressed skepticism regarding my ideological beliefs. He told me that the world could not be completely encapsulated within the boundaries of socialist philosophy. I had more or less come to this conclusion on my own, but had not admitted so much in words. Soon afterward, however, I read George Orwell's Road to Wigan Pier. This book finally undermined me—not only my socialist ideology, but my faith in ideological stances themselves. In the famous essay concluding that book (written for—and much to the dismay of—the British Left Book Club) Orwell described the great flaw of socialism, and the reason for its frequent failure to attract and maintain democratic power (at least in Britain). Orwell said, essentially, that socialists did not really like the poor. They merely hated the rich.2 His idea struck home instantly. Socialist ideology served to mask resentment and hatred, bred by failure. Many of the party activists I had encountered were using the ideals of social justice to rationalize their pursuit of personal revenge. Whose fault was it that I was poor or uneducated and unadmired? Obviously, the fault of the rich, well-schooled and respected. How convenient, then, that the demands of revenge and abstract justice dovetailed! It was only right to obtain recompense from those more fortunate than me. Of course, my socialist colleagues and I weren't out to hurt anyone. Quite the reverse. We were out to improve things—but we were going to start with other people. I came to see the temptation in this logic, the obvious flaw, the danger—but could also see that it did not exclusively characterize socialism. Anyone who was out to change the world by changing others was to be regarded with suspicion. The temptations of such a position were too great to be resisted. It was not socialist ideology that posed the problem, then, but ideology as such. Ideology divided the world up simplistically into those who thought and acted properly, and those who did not. Ideology enabled the believer to hide from his own unpleasant and inadmissible fantasies and wishes. Such realizations upset my beliefs (even my faith in beliefs), and the plans I had formulated as a consequence of these beliefs. I could no longer tell who was good and who was bad, so to speak—so I no longer knew whom to support, or whom to fight. This state of affairs proved very troublesome, pragmatically as well as philosophically. I wanted to become a corporate lawyer—had written the Law School Admissions Test, had taken two years of appropriate preliminary courses. I wanted to learn the ways of my enemies, and embark on a political career. This plan disintegrated. The world obviously did not need another lawyer, and I no longer believed that I knew enough to masquerade as a leader. I became simultaneously disenchanted with the study of political science, my erstwhile major. I had adopted that discipline so I could learn more about the structure of human beliefs (and for the practical, career-oriented reasons described previously). It remained very interesting to me when I was at junior college, where I was introduced to the history of political philosophy. When I moved to the main campus at the University of Alberta, however, my interest disappeared. I was taught that people were motivated byrational forces; that human beliefs and actions were determined by economic pressures. This did not seem sufficient explanation. I could not believe (and still do not) that commodities—“natural resources,” for example—had intrinsic and self-evident value. In the absence of such value, the worth of things had to be socially or culturally (or even individually) determined. This act of determination appeared to me moral—appeared to me to be a consequence of the moral philosophy adopted by the society, culture or person in question. What people valued, economically, merely reflected what they believed to be important. This meant that real motivation had to lie in the domain of value, of morality. The political scientists I studied with did not see this, or did not think it was relevant. My religious convictions, ill-formed to begin with, disappeared when I was very young. My confidence in socialism (that is, in political utopia) vanished when I realized that the world was not merely a place of economics. My faith in ideology departed, when I began to see that ideological identification itself posed a profound and mysterious problem. I could not accept the theoretical explanations my chosen field of study had to offer, and no longer had any practical reasons to continue in my original direction. I finished my three-year bachelor's degree, and left university. All my beliefs—which had lent order to the chaos of my existence, at least temporarily—had proved illusory; I could no longer see the sense in things. I was cast adrift; I did not know what to do or what to think. But what of others? Was there evidence anywhere that the problems I now faced had been solved, by anyone, in any acceptable manner? The customary behavior and attitudes of my friends and family members offered no solution. The people I knew well were no more resolutely goal-directed or satisfied than I was. Their beliefs and modes of being seemed merely to disguise frequent doubt and profound disquietude. More disturbingly, on the more gener-al plane, something truly insane was taking place. The great societies of the world were feverishly constructing a nuclear machine, with unimaginably destructive capabilities. Someone or something was making terrible plans. Why? Theoretically normal and well-adapted people were going about their business prosaically, as if nothing were the matter. Why weren't they disturbed? Weren't they paying attention? Wasn't I? My concern with the general social and political insanity and evil of the world— sublimated by temporary infatuation with utopian socialism and political machination— returned with a vengeance. The mysterious fact of the Cold War increasingly occupied the forefront of my consciousness. How could things have come to such a point? History is just a madhouse it's turned over all the stones and its very careful reading leaves you little that's unknown I couldn't understand the nuclear race: what could possibly be worth risking annihilation—not merely of the present, but of the past and the future? What could possibly justify the threat of total destruction? Bereft of solutions, I had at least been granted the gift of a problem. I returned to university and began to study psychology. I visited a maximum security prison on the outskirts of Edmonton, under the supervision of an eccentric adjunctprofessor at the University of Alberta. His primary job was the psychological care of convicts. The prison was full of murderers, rapists and armed robbers. I ended up in the gym, near the weight room, on my first reconnaissance. I was wearing a long wool cape, circa 1890, which I had bought in Portugal, and a pair of tall leather boots. The psychologist who was accompanying me disappeared, unexpectedly, and left me alone. Soon I was surrounded by unfamiliar men, some of whom were extremely large and tough-looking. One in particular stands out in my memory. He was exceptionally muscular, and tattooed over his bare chest. He had a vicious scar running from his collarbone to his midsection. Maybe he had survived open-heart surgery. Or maybe it was an ax wound. The injury would have killed a lesser man, anyway—someone like me. Some of the prisoners, who weren't dressed particularly well, offered to trade their clothes for mine. This did not strike me as a great bargain, but I wasn't sure how to refuse. Fate rescued me, in the form of a short, skinny, bearded man. He said that the psychologist had sent him, and he asked me to accompany him. He was only one person, and many others (much larger) currently surrounded me and my cape. So I took him at his word. He led me outside the gym doors, and into the prison yard, talking quietly but reasonably about something innocuous (I don't recall what) all the while. I kept glancing back hopefully at the open doors behind us as we got further and further away. Finally my supervisor appeared, and motioned me back. We left the bearded prisoner, and went to a private office. The psychologist told me that the harmless-appearing little man who had escorted me out of the gym had murdered two policemen after he had forced them to dig their own graves. One of the policemen had little children and had begged for his life on their behalf while he was digging—at least according to the murderer's own testimony. This really shocked me. I had read about this sort of event, of course—but it had never been made real for me. I had never met someone even tangentially affected by something like this, and had certainly not encountered anyone who had actually done something so terrible. How could the man I had talked to—who was so apparently normal (and so seemingly inconsequential)—have done such an awful thing? Some of the courses I was attending at this time were taught in large lecture theaters, where the students were seated in descending rows, row after row. In one of these courses—Introduction to Clinical Psychology, appropriately enough—I experienced a recurrent compulsion. I would take my seat behind some unwitting individual and listen to the professor speak. At some point during the lecture, I would unfailingly feel the urge to stab the point of my pen into the neck of the person in front of me. This impulse was not overwhelming—luckily—but it was powerful enough to disturb me. What sort of terrible person would have an impulse like that? Not me. I had never been aggressive. I had been smaller and younger than my classmates for most of my life. I went back to the prison, a month or so after my first visit. During my absence, two prisoners had attacked a third, a suspected informer. They held or tied him down and pulverized one of his legs with a lead pipe. I was taken aback, once again, but this time I tried something different. I tried to imagine, really imagine, what I would have to be like to do such a thing. I concentrated on this task for days and days—and experienced a frightening revelation. The truly appalling aspect of such atrocity did not lie in its impossibility or remoteness, as I had naively assumed, but in its ease. I was not muchdifferent from the violent prisoners—not qualitatively different. I could do what they could do (although I hadn't). This discovery truly upset me. I was not who I thought I was. Surprisingly, however, the desire to stab someone with my pen disappeared. In retrospect, I would say that the behavioral urge had manifested itself in explicit knowledge—had been translated from emotion and image to concrete realization—and had no further “reason” to exist. The “impulse” had only occurred, because of the question I was attempting to answer: “How can men do terrible things to one another?” I meant other men, of course—bad men—but I had still asked the question. There was no reason for me to assume that I would receive a predictable or personally meaningless answer. At the same time, something odd was happening to my ability to converse. I had always enjoyed engaging in arguments, regardless of topic. I regarded them as a sort of game (not that this is in any way unique). Suddenly, however, I couldn't talk—more accurately, I couldn't stand listening to myself talk. I started to hear a “voice” inside my head, commenting on my opinions. Every time I said something, it said something— something critical. The voice employed a standard refrain, delivered in a somewhat bored and matter-of-fact tone: You don't believe that. That isn't true. You don't believe that. That isn't true. The “voice” applied such comments to almost every phrase I spoke. I couldn't understand what to make of this. I knew the source of the commentary was part of me, but this knowledge only increased my confusion. Which part, precisely, was me—the talking part or the criticizing part? If it was the talking part, then what was the criticizing part? If it was the criticizing part—well, then: how could virtually everything I said be untrue? In my ignorance and confusion, I decided to experiment. I tried only to say things that my internal reviewer would pass unchallenged. This meant that I really had to listen to what I was saying, that I spoke much less often, and that I would frequently stop, midway through a sentence, feel embarrassed, and reformulate my thoughts. I soon noticed that I felt much less agitated and more confident when I only said things that the “voice” did not object to. This came as a definite relief. My experiment had been a success; I was the criticizing part. Nonetheless, it took me a long time to reconcile myself to the idea that almost all my thoughts weren't real, weren't true—or, at least, weren't mine. All the things I “believed” were things I thought sounded good, admirable, respectable, courageous. They weren't my things, however—I had stolen them. Most of them I had taken from books. Having “understood” them, abstractly, I presumed I had a right to them—presumed that I could adopt them, as if they were mine: presumed that they were me. My head was stuffed full of the ideas of others; stuffed full of arguments I could not logically refute. I did not know then that an irrefutable argument is not necessarily true, nor that the right to identify with certain ideas had to be earned. I read something by Carl Jung, at about this time, that helped me understand what I was experiencing. It was Jung who formulated the concept of persona: the mask that“feigned individuality.”3 Adoption of such a mask, according to Jung, allowed each of us—and those around us—to believe that we were authentic. Jung said: When we analyse the persona we strip off the mask, and discover that what seemed to be individual is at bottom collective; in other words, that the persona was only a mask of the collective psyche. Fundamentally the persona is nothing real: it is a compromise between individual and society as to what a man should appear to be. He takes a name, earns a title, exercises a function, he is this or that. In a certain sense all this is real, yet in relation to the essential individuality of the person concerned it is only a secondary reality, a compromise formation, in making which others often have a greater share than he. The persona is a semblance, a two- dimensional reality, to give it a nickname.4 Despite my verbal facility, I was not real. I found this painful to admit. I began to dream absolutely unbearable dreams. My dream life, up to this point, had been relatively uneventful, as far as I can remember; furthermore, I have never had a particularly good visual imagination. Nonetheless, my dreams became so horrible and so emotionally gripping that I was often afraid to go to sleep. I dreamt dreams vivid as reality. I could not escape from them or ignore them. They circulated, in general, around a single theme: that of nuclear war, and total devastation—around the worst evils that I, or something in me, could imagine: My parents lived in a standard ranch-style house, in a middle-class neighborhood, in a small town in northern Alberta. I was sitting in the darkened basement of this house, in the family room, watching TV, with my cousin Diane, who was in truth—in waking life—the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. A newscaster suddenly interrupted the program. The television picture and sound distorted, and static filled the screen. My cousin stood up and went behind the TV to check the electrical cord. She touched it, and started convulsing and frothing at the mouth, frozen upright by intense current. A brilliant flash of light from a small window flooded the basement. I rushed upstairs. There was nothing left of the ground floor of the house. It had been completely and cleanly sheared away, leaving only the floor, which now served the basement as a roof. Red and orange flames filled the sky, from horizon to horizon. Nothing was left as far as I could see, except skeletal black ruins sticking up here and there: no houses, no trees, no signs of other human beings or of any life whatsoever. The entire town and everything that surrounded it on the flat prairie had been completely obliterated. It started to rain mud, heavily. The mud blotted out everything, and left the earth brown, wet, flat and dull, and the sky leaden, even gray. A few distraught and shell-shocked people started to gather together. They were carrying unlabeled and dented cans of food, which contained nothing but mush and vegetables. They stood in the mud looking exhausted anddisheveled. Some dogs emerged, out from under the basement stairs, where they had inexplicably taken residence. They were standing upright, on their hind legs. They were thin, like greyhounds, and had pointed noses. They looked like creatures of ritual—like Anubis, from the Egyptian tombs. They were carrying plates in front of them, which contained pieces of seared meat. They wanted to trade the meat for the cans. I took a plate. In the center of it was a circular slab of flesh four inches in diameter and one inch thick, foully cooked, oily, with a marrow bone in the center of it. Where did it come from? I had a terrible thought. I rushed downstairs to my cousin. The dogs had butchered her, and were offering the meat to the survivors of the disaster. I dreamed apocalyptic dreams of this intensity two or three times a week for a year or more, while I attended university classes and worked—as if nothing out of the ordinary was going on in my mind. Something I had no familiarity with was happening, however. I was being affected, simultaneously, by events on two “planes.” On the first plane were the normal, predictable, everyday occurrences that I shared with everybody else. On the second plane, however (unique to me, or so I thought) existed dreadful images and unbearably intense emotional states. This idiosyncratic, subjective world—which everyone normally treated as illusory—seemed to me at that time to lie somehow behind the world everyone knew and regarded as real. But what did real mean? The closer I looked, the less comprehensible things became. Where was the real? What was at the bottom of it all? I did not feel I could live without knowing. My interest in the Cold War transformed itself into a true obsession. I thought about the suicidal and murderous preparation of that war every minute of every day, from the moment I woke up until the second I went to bed. How could such a state of affairs come about? Who was responsible? I dreamed that I was running through a mall parking lot, trying to escape from something. I was running through the parked cars, opening one door, crawling across the front seat, opening the other, moving to the next. The doors on one car suddenly slammed shut. I was in the passenger seat. The car started to move by itself. A voice said harshly, “there is no way out of here.” I was on a journey, going somewhere I did not want to go. I was not the driver. I became very depressed and anxious. I had vaguely suicidal thoughts, but mostly wished that everything would just go away. I wanted to lie down on my couch, and sink into it, literally, until only my nose was showing—like the snorkel of a diver above the surface of the water. I found my awareness of things unbearable. I came home late one night from a college drinking party, self-disgusted and angry. I took a canvas board and some paints. I sketched a harsh, crude picture of a crucified Christ—glaring and demonic—with a cobra wrapped around his naked waist, like a belt. The picture disturbed me—struck me, despite my agnosticism, as sacrilegious. I did not know what it meant, however, or why I had painted it. Where in the world had it comefrom?5 I hadn't paid any attention to religious ideas for years. I hid the painting under some old clothes in my closet and sat cross-legged on the floor. I put my head down. It became obvious to me at that moment that I had not developed any real understanding of myself or of others. Everything I had once believed about the nature of society and myself had proved false, the world had apparently gone insane, and something strange and frightening was happening in my head. James Joyce said, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”6 For me, history literally was a nightmare. I wanted above all else at that moment to wake up and make my terrible dreams go away. I have been trying ever since then to make sense of the human capacity, my capacity, for evil—particularly for those evils associated with belief. I started by trying to make sense of my dreams. I couldn't ignore them, after all. Perhaps they were trying to tell me something? I had nothing to lose by admitting the possibility. I read Freud's Interpretation of Dreams and found it useful. Freud at least took the topic seriously—but I could not regard my nightmares as wish-fulfillments. Furthermore, they seemed more religious than sexual in nature. I knew, vaguely, that Jung had developed specialized knowledge of myth and religion, so I started through his writings. His thinking was granted little credence by the academics I knew, but they weren't particularly concerned with dreams. I couldn't help being concerned by mine. They were so intense I thought they might derange me. (What was the alternative? To believe that the terrors and pains they caused me were not real?) Much of the time I could not understand what Jung was getting at. He was making a point I could not grasp, speaking a language I did not comprehend. Now and then, however, his statements struck home. He offered this observation, for example: It must be admitted that the archetypal contents of the collective unconscious can often assume grotesque and horrible forms in dreams and fantasies, so that even the most hard-boiled rationalist is not immune from shattering nightmares and haunting fears.7 The second part of that statement certainly seemed applicable to me, although the first (“the archetypal contents of the collective unconscious”) remained mysterious and obscure. Still, this was promising. Jung at least recognized that the things that were happening to me could happen. Furthermore, he offered some hints as to their cause. So I kept reading. I soon came across the following hypothesis. Here was a potential solution to the problems I was facing—or at least the description of a place to look for such a solution: The psychological elucidation of…[dream and fantasy] images, which cannot be passed over in silence or blindly ignored, leads logically into the depths of religious phenomenology. The history of religion in its widest sense (including therefore mythology, folklore, and primitive psychology) is a treasure-house of archetypal forms from which the doctor can draw helpful parallels and enlightening comparisons for the purpose of calming and clarifying a consciousness that is all at sea. It is absolutely necessary to supply these fantastic images that rise up so strange and threatening before the mind's eye with some kind of context so as to makethem more intelligible. Experience has shown that the best way to do this is by means of comparative mythological material. The study of “comparative mythological material” in fact made my horrible dreams disappear. The cure wrought by this study, however, was purchased at the price of complete and often painful transformation: what I believe about the world, now—and how I act, in consequence—is so much at variance with what I believed when I was younger that I might as well be a completely different person. I discovered that beliefs make the world, in a very real way—that beliefs are the world, in a more than metaphysical sense. This discovery has not turned me into a moral relativist, however: quite the contrary. I have become convinced that the world-that-is- belief is orderly; that there are universal moral absolutes (although these are structured such that a diverse range of human opinion remains both possible and beneficial). I believe that individuals and societies who flout these absolutes—in ignorance or in willful opposition—are doomed to misery and eventual dissolution. I learned that the meanings of the most profound substrata of belief systems can be rendered explicitly comprehensible, even to the skeptical rational thinker—and that, so rendered, can be experienced as fascinating, profound and necessary. I learned why people wage war—why the desire to maintain, protect and expand the domain of belief motivates even the most incomprehensible acts of group-fostered oppression and cruelty—and what might be done to ameliorate this tendency, despite its universality. I learned, finally, that the terrible aspect of life might actually be a necessary precondition for the existence of life—and that it is possible to regard that precondition, in consequence, as comprehensible and acceptable. I hope that I can bring those who read this book to the same conclusions, without demanding any unreasonable “suspension of critical judgment”—excepting that necessary to initially encounter and consider the arguments I present. These can be summarized as follows: The world can be validly construed as a forum for action, as well as a place of things. We describe the world as a place of things, using the formal methods of science. The techniques of narrative, however—myth, literature and drama—portray the world as a forum for action. The two forms of representation have been unnecessarily set at odds, because we have not yet formed a clear picture of their respective domains. The domain of the former is the objective world—what is, from the perspective of intersubjective perception. The domain of the latter is the world of value—what is and what should be, from the perspective of emotion and action. The world as forum for action is composed, essentially, of three constituent elements, which tend to manifest themselves in typical patterns of metaphoric representation. First is unexplored territory—the Great Mother, nature, creative and destructive, source and final resting place of all determinate things. Second is explored territory—the Great Father, culture, protective and tyrannical, cumulative ancestral wisdom. Third is the process that mediates between unexplored and explored territory—the DivineSon, the archetypal individual, creative exploratory Word and vengeful adversary. We are adapted to this world of divine characters, much as to the objective world. The fact of this adaptation implies that the environment is in “reality” a forum for action, as well as a place of things. Unprotected exposure to unexplored territory produces fear. The individual is protected from such fear as a consequence of ritual imitation of the Great Father—as a consequence of the adoption of group identity, which restricts the meaning of things, and confers predictability on social interactions. When identification with the group is made absolute, however—when everything has to be controlled, when the unknown is no longer allowed to exist—the creative exploratory process that updates the group can no longer manifest itself. This restriction of adaptive capacity dramatically increases the probability of social aggression. Rejection of the unknown is tantamount to “identification with the devil,” the mythological counterpart and eternal adversary of the world-creating exploratory hero. Such rejection and identification is a consequence of Luciferian pride, which states: all that I know is all that is necessary to know. This pride is totalitarian assumption of omniscience—is adoption of God's place by “reason”—is something that inevitably generates a state of personal and social being indistinguishable from hell. This hell develops because creative exploration—impossible, without (humble) acknowledgment of the unknown—constitutes the process that constructs and maintains the protective adaptive structure that gives life much of its acceptable meaning. “Identification with the devil” amplifies the dangers inherent in group identification, which tends of its own accord towards pathological stultification. Loyalty to personal interest-subjective meaning—can serve as an antidote to the overwhelming temptation constantly posed by the possibility of denying anomaly. Personal interest—subjective meaning—reveals itself at the juncture of explored and unexplored territory, and is indicative of participation in the process that ensures continued healthy individual and societal adaptation. Loyalty to personal interest is equivalent to identification with the archetypal hero—the “savior”—who upholds his association with the creative Word in the face of death, and despite group pressure to conform. Identification with the hero serves to decrease the unbearable motivational valence of the unknown; furthermore, provides the individual with a standpoint that simultaneously transcends and maintains the group. Similar summaries precede each chapter (and subchapter). Read as a unit, they comprise a complete but compressed picture of the book. These should be read first, after thispreface. In this manner, the whole of the argument I am offering might come quickly to aid comprehension of the parts.

Pages

- Index of Lessons in Technology

- Index of Book Summaries

- Index of Book Lists And Downloads

- Index For Job Interviews Preparation

- Index of "Algorithms: Design and Analysis"

- Python Course (Index)

- Data Analytics Course (Index)

- Index of Machine Learning

- Postings Index

- Index of BITS WILP Exam Papers and Content

- Lessons in Investing

- Index of Math Lessons

- Downloads

- Index of Management Lessons

- Book Requests

- Index of English Lessons

- Index of Medicines

- Index of Quizzes (Educational)

Monday, July 31, 2023

Descensus ad inferos (Descended into hell)

Monday, July 24, 2023

Smoothing (Part of Data Analytics Course)

Highlighting Algorithm Followed For Smoothing The Data

1. Decide which kind of binning you want to use?

- Equal frequency

- Equal width

2. Once you have binned the data, you have to decide whether you are going to assign the bin with a value from:

- mean

- median

- boundary

3. Replace each bin value by the formula selected in Step 2.

Smoothing(noisy data)

Suppose a group of 12 sales price records has been sorted as follows:

5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 35, 50, 55, 72, 92, 204, 215

Partition them into three bins by each of the following methods.

Equal-frequency partitioning

What is Smoothing by bin mean/median/boundary?

How do we define the first bin?

We need a bin that encloses 5, 10 and 11.

(4.5, 11.5]: This is also correct but let’s look at Pandas.

What Pandas has created is:

(4.999, 12.5]: Range exlusive of 4.999 and starting from there. Also range inclusive of 12.5 and ending there.

Is it wrong? No.

Next bin:

(12.5, 42.5]: Is it wrapping the elements 13, 15 and 35?

Next bin would start at 42.5. Can we say this?

Smoothing(noisy data)

Suppose a group of 12 sales price records has been sorted as follows:

5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 35, 50, 55, 72, 92, 204, 215

Partition them into three bins by each of the following methods.

Equal-frequency partitioning

What is Smoothing by bin mean/median/boundary?

Replace each bin value is replaced by mean/median/nearest boundary

On smoothing by bin-boundary (bins follow equal-frequency partitioning):

Bin 1: 5, 13, 13, 13

As 5 is closer to boundary value ‘5’. And, 10, 11 are closer to boundary value ‘13’

Bin 2: 15, 15, 55, 55

Bin 3: 72, 72, 215, 215

Original:

Smoothing by equal-frequency binning using the mean of each bin

1. creation of bins In code: pd.qcut()

2. grouping the data according to bins In code: df.groupby()

3. find the mean of each group In code: df.groupby().mean()

4. create a map of bin labels and mean values In code: it is essentially a dictionary that looks like this: { '(4.999, 14.333]': 9.75, '(14.333, 60.667]': 38.75, '(60.667, 215.0]': 145.75 } A dictionary is simply key-value pairs. 5. Populate a new column containing the mean of each bin for each data point.

Smoothing (noisy data)

Suppose a group of 12 sales price records has been sorted as follows:

5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 35, 50, 55, 72, 92, 204, 215

Partition them into three bins by each of the following methods.

Equal-width partitioning

The width of each interval is (215 - 5)/3 = 70.

Perform Smoothing by bin mean/median/boundary.

Bins using equal width partitioning.

Elements: 5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 35, 50, 55, 72, 92, 204, 215

The width of each interval is (215 – 5)/3 = 70.

Domain for bin-1: 5 up to, but not, 75 (= 5 + 70)

Domain for bin-2: 75 to 144

Domain for bin-3: 145 Onwards (inc. 215 from the input data set)

Data Analytics Course Using Python (Index)

Chapters

- Data Analytics Books (May 2023)

- Ch 1: What is Data Mining?

- Ch 2: Descriptive Statistics

- Ch 3: Scaling and Normalization

- Ch 4: Smoothing

- Ch 5: Similarity, dissimilarity and distance

Chapters Pending Publication

- (6) decision tree

- (7) measuring classification

- (8) linear regression between two variables

- (9) categorical encoding

- (10) naive bayes classifier

- (11) logistic regression

- (12) support vector machines

- (13) one-vs-rest and one-vs-one strategies for multiclass classification

- (14) generalization and overfitting

- (15) kNN classification

- (16) clustering and kmeans

- (17) clustering (kmeans)

- (18) clustering (agglomerative hierarchical clustering)

- (19) clustering - dbscan

- (20) cluster evaluation

- (21) random forest

- (22) five regression algorithms

- (23) Ensemble techniques

- Exercises

Equal Frequency Binning (Part of Data Analytics Course)

import pandas as pd l = [5, 10, 11, 13, 15, 35, 50, 55, 72, 92, 204, 215] s = pd.Series(l) s.nunique() 12 bins = pd.qcut(s, 3) # Equal frequency binningHow do we make data smooth using mean?

df = pd.DataFrame( { 'data': l, 'bins': bins } ) df t = df.groupby(['bins']).mean(['data']) t map_of_mean_values = {} for i in t.iterrows(): # type(i[0]): Interval # type(i[1]): Series map_of_mean_values.update({str(i[0]): i[1][0]}) map_of_mean_values {'(4.999, 14.333]': 9.75, '(14.333, 60.667]': 38.75, '(60.667, 215.0]': 145.75} df['bins'] = df['bins'].astype(str) df['smoothed_values'] = df['bins'].apply(lambda x: map_of_mean_values[x]) df

Sunday, July 23, 2023

Functions in Python

What is a Function?

A function is a block of code.

It runs when it is called with pair of parenthesis at the end.

There are some functions which are built-in like: print(), input(), type(), len(), list(), etc.

There are also functions which are user defined.

We can pass data to function through parameter. Parameters are separated by commas.

We can pass any number of arguments into a function.

And a function can return data as result.

Parameters or Arguments ?

Both term’s are used for the Information passed into a function

First Function

A function is defined using the “def” keyword.

A function has a name and a body.

It may or may not have parameters (or arguments).

def my_function():

print("Hello from a function")

Name: my_function

Arguments: no args

Body: print()

Problem

- Create a function that takes an integer as input and tells whether it is divisible by 7.

def div_by_7(x):

if x % 7 == 0:

print("yes, it is divisible by ")

else:

print("no, not divisible by 7")

x = int(input("Enter a natural number: "))

div_by_7(x)

Problem: Passing of Arguments (With Name and Without Name)

# Passing arguments with keywords i.e ( bind arguments with parameters name )

# Ordering of parameter has no mean in this case

# define a function with three parameter

def get_youngest_child(child3, child2, child1):

print("The youngest child is " + child3)

# What will be output?

get_youngest_child("Emil", "Tobias", "Linus")

# Calling of function by passing key value pairs, order does not matter

get_youngest_child(child1 = "Emil", child2 = "Tobias", child3 = "Linus")

Argument Passing With / Without Names

Argument passing by positions:

First argument goes to the first variable, second argument goes to the second variable, so on, so forth.

def get_youngest_child(child3, child2, child1):

get_youngest_child("Emil", "Tobias", "Linus")

Argument passing by name

def get_youngest_child(child3, child2, child1):

get_youngest_child(child1 = "Emil", child2 = "Tobias", child3 = "Linus")

CreditsMethod vs. Function: Difference Between Methods and Function

Definition Method: Method definitions are always present inside a class. Function: No class is needed to define a function. Association Method: Associated with the class object. Function: Not associated with any objects. Call Method: It is called on an object. Function: It is called by its name. Dependency Method: It depends on the class they belong to. Function: It doesn’t depend on any class, i.e., it is an identical entity. self Method: It requires the self as its first argument. Function: It doesn’t require any self-argument. Operation Method: It operates on the data of the object it associates with. Function: It operates on the data that you pass to them as an argument.Local Variable and Global Variable

Take a look at this code: If you run the program, you will get the output below. INSIDE THE FUNCTION Global Variable Local Variable OUTSIDE THE FUNCTION Global Variable NameError: name 'message2' is not defined In the code above, message1 is a global variable while message2 is a local variable declared inside the function myFunction(). Within the function, both the local and global variables are accessible. Outside the function, the local variable message2 is no longer accessible. We get a NameError when we try to access it outside the function. The second concept to understand about variable scope is that if a local variable shares the same name as a global variable, any code inside the function is accessing the local variable. Any code outside is accessing the global variable. Try running the code below: You’ll get the output as follows: INSIDE THE FUNCTION Local Variable (shares same name as a global variable) OUTSIDE THE FUNCTION Global Variable (shares same name as a local variable)Default Parameter Values

Now that we understand how functions and variable scope work, let us look at some interesting variations that Python allows when defining a function. First, let’s look at default values. Python allows us to define default values for the parameters of a function. If a parameter has a default value, we do not have to pass in any value for the parameter when calling the method. For instance, suppose a function has 5 parameters a, b, c, d and e. We can define the function as def someFunction(a, b, c=1, d=2, e=3): print(a, b, c, d, e) Here, we assign default values for the last three parameters. All parameters with default values must be placed at the end of the parameter list. In other words, we cannot define a function as follows because r comes after q which has a default value: def someIncorrectFunction(p, q=1, r): print(p, q, r) To call someFunction(), we can write someFunction(10, 20) we’ll get 10, 20, 1, 2, 3 We do not have to pass in any values for c, d and e. If we write someFunction(10, 20, 30, 40) we’ll get 10, 20, 30, 40, 3 The two additional arguments that we pass in (30 and 40) are assigned to the parameters with default values in order. Hence, 30 replaces the default value for c while 40 replaces d.Variable Length Argument List

In addition to having default values for parameters, Python also allows us to pass a variable number of arguments to a function. This is very useful if we do not know the number of arguments a function has in advance. For instance, we may have a function that adds a series of numbers, but we do not know how many numbers there are in advance. In cases like this, we can use the * symbol. The example below shows how this can be done. def addNumbers(*num): sum = 0 for i in num: sum = sum + i print(sum) When we add a single asterisk in front of num, we are telling the compiler that num stores a variable-length argument list that contains several items. The function then loops through the argument to find the sum of all the numbers and return the answer. To call the function, we write addNumbers(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) we’ll get 15 as the output. We can also add more numbers by writing addNumbers(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) we’ll get 36 as the output. As we can see in the examples above, when we add an asterisk in front of a parameter name, we can pass in a variable number of arguments to the function. This is known as a non-keyworded variable length argument list. If we want to pass in a keyworded variable length argument list to the function, we can use double asterisks. For instance, consider the following example: def printMemberAge(**age): for i, j in age.items(): print("Name = %s, Age = %s" %(i, j)) This function has a parameter called age. The double asterisks denote that this parameter stores a keyworded variable length argument list, which is essentially a dictionary. The for loop then loops through the argument and prints out the values. To call the function, we can write printMemberAge(Peter = 5, John = 7) we’ll get Name = Peter, Age = 5 Name = John, Age = 7 If we write printMemberAge(Peter = 5, John = 7, Yvonne = 10) we’ll get Name = Peter, Age = 5 Name = John, Age = 7 Name = Yvonne, Age = 10 If our function uses a normal argument (also known as a formal argument), a non-keyworded variable length argument list and a keyworded variable length argument list, we must define the function using the following order: def someFunction2(farg, *args, **kwargs): That is, the formal argument must come first, followed by the non-keyworded argument and the keyworded argument in that order.

Aman Kumar

Python Course (Index)

Posts With Videos

Chapters

- Ch 1 - Python's builtin functions

- Ch 2 - Operators in Python

- Ch 3 - 7 Problems on Operators and Variables

- Ch 4 - Problems on Operator Precedence

-

Ch 5 - Strings in Python

- Ch 6 - 5 Problems on strings (Using Python)

- Ch 7 - String Related Functionality in Python

- Ch 8 - Lists in Python

- Ch 9 - 14 Problems on lists in Python

- Ch 10 - Python 'math' Module, 'statistics' Module and Descriptive statistics using Pandas, NumPy, SciPy and StatsModels

- Ch 11 - Understanding ASCII Values For Characters Using Python

- Ch 12 - Working with Tuples (in Python)

- Ch 13 - Sets (in Python)

- Ch 14 - Python Dictionaries

- Ch 15 - If, Elif, Else, For, While, Pass, Break and Continue

- Ch 17 - 2D Matrix in Python

- Ch 18 - Functions

- Ch 19 - Python Classes and Objects (Theory)

- Ch 20 - Inheritance in Python (Theory)

- Ch 21 - Iterators (Theory)

- Ch 22 - Exception Handling

- Ch 23 - Python's Standard Library and Built-in Modules

Posts pending publication

- Ch 24 - Custom/External Modules

- Ch 25 - Regex

- Ch 26 - Basic Project

- Ch 27 - Flask

- Ch 28 - SQLite

- Ch 29 - NumPy

- Chapter on Git and GitHub

- Exercises

Miscellaneous

- Password Encryptor Using Python

- Logging in Python

- 7 Frequent Python 'os' Package Uses

- Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) : Highlights (Book by Steven Bird) [Tags: Natural Language Processing, Python]

- Python 2, python 3, base64, string and bytes

Credits

- Yajuvendra Gupta

- Aman Kumar

2-D Matrix in Python

Indices in a 1D List

1-D List

What is a 2D Matrix?

This 2D matrix has got 3 rows and 3 columns.

Contents of Row 0: A B C

Contents of Row 1: D E F

Contents of Row 2: G H I

Contents of Col 0: A D G

Contents of Col 1: B E H

Contents of Col 2: C F I

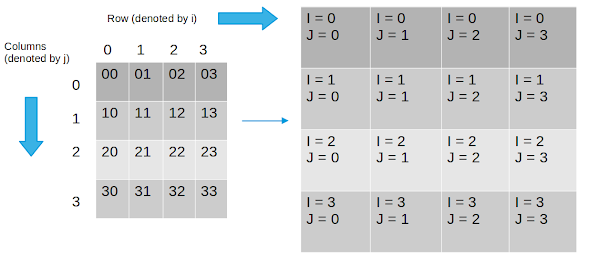

Indices in a 2D Matrix of Shape 2 X 2

Indices in a 2D Matrix of Shape 3 X 3

Indices in a 2D Matrix of Shape 4 X 4

Square Matrices And Rectangular Matrices (Part 1)

Matrices of shape: 2X2, 3X3 and 4X4 were square matrices.

Square matrix has same number of rows and columns.

Rectangular matrix has number of rows different from number of columns.

Two columns

Three rows

Shape of a matrix is given by:

Number of rows X Number of cols

Shape of this matrix is: 3X2

Problem on Square Matrices And Rectangular Matrices

Q1: How many rows does it have?

Q2: How many columns does it have?

Q3: What is its shape?

Answers:

1) 3

2) 5

3) Rectangle of shape 3X5

Problem 1

- Ques: Create a 2D matrix programmatically using for loop with following contents:

- [ [1, 2, 3],

- [4, 5, 6],

- [7, 8, 9] ]

- The matrix should not hardcoded but created using for loop.

Solution 1

- [

- [1, 2, 3], # This is your first row

- [4, 5, 6], # This is your second row

- [7, 8, 9] # This is your third row

- ]

r = 3 # Number of rows

c = 3 # Number of columns

mylist = []

cntr = 1

for i in range(r):

# This means loop will run r times.

temp = []

for j in range(c):

temp.append(cntr)

cntr += 1

mylist.append(temp)

print(mylist)

A 2D matrix is essentially a list of lists.

First, (i) will be 0. (j) will go from 0, 1, 2.

Then, (i) will be 1. (j) will go from 0, 1, 2.

Lastly, (i) will be 2. (j) will go from 0, 1, 2.

import numpy as np

n = np.array(range(1, 10))

n.reshape(3, 3)

Problem 2

- Ques: This matrix is given to you:

- [ [1, 2, 3],

- [4, 5, 6],

- [7, 8, 9] ]

- You have to add 5 to each number in this matrix.

- Addition of 5 to each element in the matrix.

Solution 2

Way 1:

arr = [ [1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9] ]

for i in arr:

for j in i:

print(j + 5)

print("Further if we want to create a new array")

mod_arr = []

for i in arr:

templist = []

for j in i:

templist.append(j+5)

mod_arr.append(templist)

print(mod_arr)

Way 2: Using numpy

import numpy as np

arr = np.array(arr)

arr += 5

print(arr)

[[ 6 7 8]

[ 9 10 11]

[12 13 14]]

Problem 3

m = [

[0, 1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6, 7],

[8, 9, 10, 11],

[12, 13, 14, 15]

]

""" What is the position of 6?

What is the position of 8?

What is the position of 10?

What is the position of 12?

"""

Solution 3

m = [ [0, 1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6, 7], [8, 9, 10, 11], [12, 13, 14, 15]]

""" What is the position of 6?

Ans: [1][2]

What is the position of 10?

Ans: [2][2]

What is the position of 12?

Ans: [3][0]

"""

Diagonal of a Square Matrix (Top Left to Bottom Right)

Problem: Printing the two diagonals

Print the diagonals:

m = [['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'], ['E', 'F', 'G', 'H'],

['I', 'J', 'K', 'L'], ['M', 'N', 'O', 'P']]

Solution

matrix = [['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'], ['E', 'F', 'G', 'H'], ['I', 'J', 'K', 'L'], ['M', 'N', 'O', 'P']]

# Given a two dim. matrix

rows = cols = len(matrix)

print("Diagonal top-left to bottom-right")

for i in range(rows):

for j in range(cols):

if(i == j):

print(matrix[i][j])

print("Diagonal top-right to bottom-left")

for i in range(rows):

for j in range(cols):

if(i + j == rows - 1):

print(matrix[i][j])

Printing diagonals using numpy

matrix = [['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'], ['E', 'F', 'G', 'H'], ['I', 'J', 'K', 'L'], ['M', 'N', 'O', 'P']]

matrix = np.array(matrix)

print(matrix)

[['A' 'B' 'C' 'D']

['E' 'F' 'G' 'H']

['I' 'J' 'K' 'L']

['M' 'N' 'O' 'P']]

matrix.diagonal()

array(['A', 'F', 'K', 'P'], dtype='<U1')

# fliplr() : flip left to right

print(np.fliplr(matrix))

print(np.fliplr(matrix).diagonal())

[['D' 'C' 'B' 'A']

['H' 'G' 'F' 'E']

['L' 'K' 'J' 'I']

['P' 'O' 'N' 'M']]

['D' 'G' 'J' 'M']

Printing upper triangle and lower triangle

m = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

np.triu(m)

array([[1, 2, 3],

[0, 5, 6],

[0, 0, 9]])

np.tril(m)

array([[1, 0, 0],

[4, 5, 0],

[7, 8, 9]])

Credits Aman Kumar

Attachment for the unnecessary and superfluous (A Story)

The following fairy tale is a “wakeup call” from the psychological “unconscious”. Once upon a time there was a man who had a long hard journey ahead of him. He was trudging along the way, over the boulders and through the brushes, when he saw a little shiny gnome with big white teeth and a black toupee sitting by the side of the road. He was drumming on a log with two white bones, and humming oddly to himself. The little gnome said, “John—why work so hard? Why walk so fast? Who knows if you'll ever get there anyway? Come over here. I have something to show you.” So John walked off the road. He was sick of walking, anyhow, because people kept throwing sticks and stones at him. The little gnome said, “I have a shiny red jewel I would like to sell you. Cheap. Here it is,” and from beneath his cloak he pulled the biggest ruby that the man had ever seen. It must have weighed a hundred pounds, and it shone like the sun. The gnome said, “Do you like it? It is an enchanted stone. What will you offer me for it?” and the man said, “I don't have much—much money. But I will give you everything I have.” The gnome looked displeased, so John added: “I could pay some more monthly.” So the gnome accepted: “Fair enough! Buy now, pay later. Sounds good to me. I'm all for the installment plan.” So the man gave the gnome all his money, and promised to pay the rest later. And the gnome walked back into the bush by the road, clacking his teeth and giggling and twitching. The more the man thought about his ruby, and the great deal he got, the happier he became. He started back on the road, with a light heart, but soon discovered that he couldn't make much progress, because a hundred pounds was a lot to carry. He said to himself: “Why continue, anyway? I have what I want. Why don't I just stand here, holding my ruby—and when people walk by, they can see how well I have already done!” So he stopped. A little while later, one of his friends came along, and saw him standing there. His friend said, “John, why don't you come along with me? I have just opened a new business, and I could really use some help! Come along quick! It will be opening soon!” John thought that sounded good, but his friend was in a hurry. Besides, couldn't he see the ruby? How could he speed along beside him? Where would he put his jewel? So he said, “Thanks, but I have to take care of my jewel. Maybe I'll see you later.” His friend looked at him like he was crazy—but he was trying to get somewhere quick. So he just shrugged a bit and said, “Okay, John. See you later,” and he sped on down the road. A little while later, another friend came by, and he said, “John! Nice to see you! I am going back to school! There are lots of wonderful things to learn! Lots of great things to do! The world is full of unsolved problems! I could use some company! Would you like to come along?” John thought that sounded pretty good—but this friend, too, looked like he was in a hurry. Besides, standing beside the road, holding the jewel, was tiring, and he needed all the energy he had for that. So he said to his friend, “Thanks, but I have to take care of my jewel. Isn't it beautiful? Maybe I'll see you later.” His friend looked at him like he was crazy—but he was trying to get somewhere quick. So he just shrugged and said, “Hope everything goes all right with you. See you later.” Many friends came and went, and the years went by. The jewel got heavier and heavier, but the man got more and more attached to it. The only thing was, nobody seemed to notice how beautiful it was. People would rush by, and talk about their plans and nobody had a ruby as big and nobody seemed likely to get a ruby as big so you'd think that someone might have said something something, at least, like “Nice ruby, John. Sure wish I had one like that.” But it never happened. Then one day someone new came down the road. He was bent over, and he was thin, and his hair was gray, although he did not look that old. He was carrying a big, dirty rock carefully in his arms, and he was not making much progress. The strange figure approached and glanced up at John. Then he grinned and said, “Why are you standing there stupidly, with a big ugly rock in your tired old hands? You look pretty daft. I bet you wish you had a big ruby, like the one I am carrying!” and John thought, “This poor man is deluded. He is carrying a rock—it is I who have the ruby!” so he said, “Excuse me sir, but you are sadly mistaken. I am the one with the jewel. I met a little gnome by the side of the road, and he sold it to me. I am still paying for it—although not so very much! You are carrying a rock!” The tired stranger looked annoyed. He said, “I don't know what game you are playing, mister. You have a rock. I have a jewel. The little gnome you described sold it to me—and he said it was the only one! I have been carrying it for twenty years, and I will never let it go!” and John said, “But I have been carrying mine for twenty years, too. It can't be just a rock!” Rock or jewel? On and on they argued. Suddenly, out stepped the little gnome, as if he had never left! Only this time, he wasn't so little. He was bigger, and redder, and menacing, and his laugh sounded like the rattling of chains. “Quit arguing, you two! I've never seen a sight quite so pathetic. You're carrying rocks—both of you. And if you ever would have had the sense to put them down for a second or two, you would have seen that! “Oh well, at least you were diligent. And I played a mean trick. I feel bad. “So, I'm going to give you what you really deserve. Do you want what you really deserve?” and John and the thin stranger nodded eagerly. Finally, they thought. “You haven't seen anything yet. Throw down your rocks!” So John and the thin stranger obeyed. Each rock split down the middle, when it hit the ground. Out flowed a river of ravenous white worms, which rushed toward the men and devoured them whole, while they thrashed about and screamed. Soon, nothing was left except a leg bone from each. The little gnome picked them up, and walked off the road. He sat down by a hollow log, and started to drum. He drummed, and he waited, and he hummed an odd little tune: “A picture of food feeds the whole hungry clan the image of good makes the whole healthy man Why walk the mile? Why do the work? Just smile the smile! Success after all is a quirk! Life isn’t real that’s the message I give It’s easy that way plus who wants to live?” Reference Maps of Meaning (Architecture of Belief) by Jordan Peterson