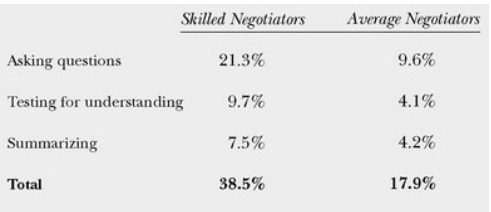

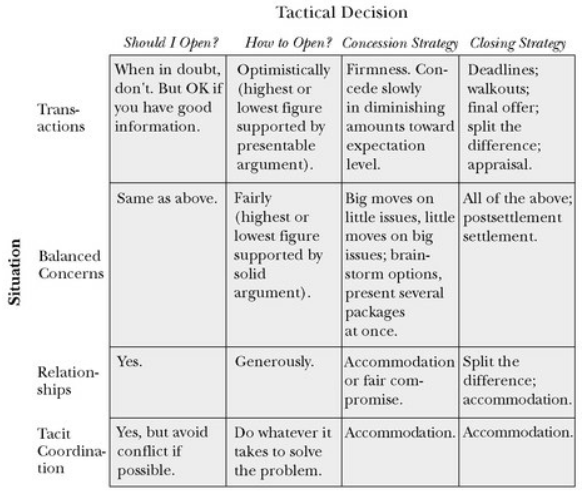

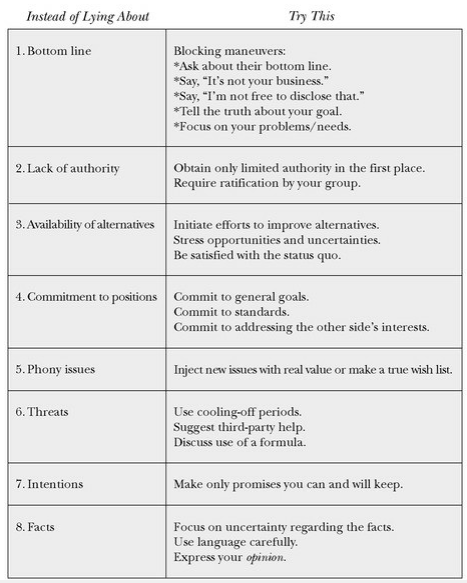

Introduction First, all deals that close are win-win deals. The last twenty-five years has seen a veritable explosion of negotiation research and writing—but it is relatively inaccessible. Negotiation scholars publish their findings on negotiation in academic journals and books that most real-world negotiators do not read. And it is hard for reasonable people to sift the good advice from the bad in the popular writing on bargaining. Just because a technique works well for a sports celebrity or Hollywood agent does not mean it will work for you. So you should "Look Inside Your Toolbox: It’s Your Move" PART I - THE SIX FOUNDATIONS OF EFFECTIVE NEGOTIATION CHAPTER 1 - The First Foundation: Your Bargaining Style You must bake with the flour you have. —DANISH FOLK SAYING A negotiation is an interactive communication process that may take place whenever we want something from someone else or another person wants something from us. Five Strategies and Negotiation Styles: A Thought Experiment To begin our exploration of your bargaining strengths, try the following thought experiment. Imagine you are one of ten people, all of whom are strangers, sitting at a big round table in a conference room. Someone comes into the room and makes the following offer: “I will give a prize of one thousand dollars to each of the first two people who can persuade the person sitting opposite to get up, come around the table, and stand behind his or her chair.” Do you have that picture in mind? You are one of the ten strangers at the table. You can see the person sitting opposite you, and that person is looking at you. The first two people who can persuadethe person sitting opposite to get up, come around the table, and stand behind his or her chair gets $1,000. Everyone else gets nothing. What strategy would you use to respond to this strange offer? You will need to move quickly because everyone else is also thinking about what to do. Before reading on, close your eyes and think of your response. Note what strategy comes to your mind first and write it down. Then see what other responses you can think of. The possibilities will help me introduce five generic negotiating strategies, which will, in turn, lead us to a deeper look at your personality as a negotiation variable. One reaction is to sit tight and do nothing, suspecting a trick or worrying that you might look like a fool running around a table in response to a stranger’s offer. “I don’t like to negotiate, so I don’t do it unless I have to,” you might say. This is the avoiding response favored by the Internet entrepreneur I mentioned above. Some people might say that avoiding a negotiation is a cop-out, not a bargaining strategy. But you do not have to look very far to notice that many important negotiations are marked by one side or the other studiously avoiding coming to the table. The North Koreans successfully avoided negotiating over their nuclear weapons programs for years—and built up bargaining leverage in the meantime. Presidential candidates in the United States who find themselves ahead in the polls frequently decline to negotiate when their opponents want to increase the number of presidential debates. In general, avoiding is a good strategy when you are happy with the status quo—but it may not be the best approach to the table problem. Perhaps the most obvious response is to offer the person sitting opposite you $500 if he or she will race around and stand behind your chair. This is the compromise solution. Each person agrees to share the gains equally between them. Compromise is a simple, fair, fast strategy that resolves many negotiations amicably. But is it a good strategy for the table problem? You and your partner may arrive at a quick agreement to split the money evenly, but which of you should run and who should sit? During the few seconds it takes to address this issue, other people are already racing around the table. There is no compromise solution to the question of which of you should run—so a simple compromise does not fully solve the problem. An additional strategy is needed. That strategy is our third candidate—accommodation. You could simply get up and run behind your opposite’s chair. If you do this in response to your partner’s offer to split the money, you can refer to that promise as a bargaining standard in any subsequent negotiation over the money. But there may be no money to split. The people who implemented the 100 percent accommodating strategy took off as soon as they heard the stranger’s offer and got to their partners’ chairs before you did. But they face a problem, too. The lucky people who were the beneficiaries of the accommodating strategy now have $1,000 and the people who ran have nothing. These helpful negotiators must trust the people for whom they earned the money to share it—without the benefit of a prior commitment on how it will be shared. And remember—everyone at the table is a stranger who never expects to see their counterpart again. The fourth response embodies the competitive strategy. The idea here is to obtain the entire $1,000 as well as the power to decide how it will be shared. One way might be to offer to split the money 50-50 and then later refuse to do so—to renege on your promise. That would obviously be unethical, but some people might do it. After all, there was no mention of a court system to litigate disputes about who said what. An even more aggressive stance would be to lie and say you have a broken leg so you can’t move, begging your partner to run as quickly as possible. Are all competitive strategies as ethically dubious as these two? No. We will see examples of many competitive strategies in the pages ahead that are perfectly ethical under any system of morals. But the table problem is notstructured well for a strategy that is both ethical and competitive. Moreover, this strategy, like the compromise approach, may take too long to implement. The final strategy is the most imaginative, given the terms of the offer. You get out of your chair, start running, and scream: “Let’s both get behind each other’s chairs! We can each make a thousand dollars!” This can work—if you are quick enough. This is the collaborative or problem-solving strategy. Instead of trying to figure out how to divide $1,000 two ways, the person using this approach has the insight to see that there is a way for both parties to get $1,000 out of the situation. The collaborative strategy is often the hardest to implement. It seeks to discover the underlying problem through good analysis and candid disclosure of interests, find the most elegant solution by brainstorming many options, and resolve tough issues using fair standards and criteria. In many ways, it represents an ideal. As we shall see, problem-solving strategies are especially useful in complex negotiations, such as those faced by international diplomats or corporate negotiators doing mergers or acquisitions. They can also play a useful role in family negotiations, where it is vitally important to avoid having “winners” and “losers.” But many obstacles stand in the way of collaborative approaches, such as lack of trust between the parties, greed, personality, cultural differences, and simple lack of imagination. Cooperative Versus Competitive Styles A study of American lawyer-negotiators reported by Professor Gerald R. Williams revealed that roughly 65 percent of a sample of attorneys from two major U.S. cities exhibited a consistently cooperative style of negotiation, whereas only 24 percent were truly competitive in their orientation (11 percent defied categorization using these two labels). Roughly half of the sample was rated as “effective” negotiators by their peers. Most interesting, more than 75 percent of the “effective” group were cooperative types and only 12 percent were competitive. The remaining effective negotiators came from the pool of mixed strategy negotiators. The second study was conducted over a period of nine years by Neil Rackham and John Carlisle in England. Rackham and Carlisle observed the behavior of forty-nine professional labor and contract negotiators in real transactions. The point I want to make here relates to the styles exhibited by these professionals. The most effective of them displayed distinctly cooperative traits. For example, the study examined the use of what the researchers called irritators at the negotiating table. Irritators are such things as self-serving descriptions of one’s offer, gratuitous insults, and direct attacks on the other side’s proposal—typical competitive tactics. The average negotiator used 10.8 irritators per hour of negotiating time; the more skilled negotiators used an average of only 2.3 irritators per hour. In addition, skilled negotiators avoided what the researchers called defend/attack spirals, cycles of emotion-laden comments assigning blame or disclaiming fault. Only 1.9 percent of the skilled negotiators’ comments at the table fell into this category, whereas the average negotiators triggered or gave momentum to defend/attack spirals with 6.3 percent of their comments. The profile of the effective negotiator that emerges from this study seems to reflect a distinct set of cooperative, as opposed to stereotypically competitive, traits. Contrary to popular belief, perfectly reasonable, cooperative people appear to have a strong potential to become extremely effective negotiators. THE GENDER DIFFERENCE IN NEGOTIATION Studies indicate that men and women can differ in the ways they communicate—especially in work settings. Georgetown linguistics professor Deborah Tannen has demonstrated in books such as You Just Don’t Understand: Men and Women in Conversation and Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men at Work that men tend to be more assertive, more likely to interrupt their counterpart, and more oriented toward affirming their status. Women, meanwhile, listen more than men do and pay greater attention to emotional rapport and taking turns when speaking. Although you probably know plenty of emotionally oriented men and status-oriented women, the statistics support Tannen’s overall findings. The question then becomes how these various behavioral tendencies can be used or adapted so theyare sources of strength rather than weakness in particular professional contexts. Research on American women suggests that there are two main ways that gender differences affect negotiations. First, there is solid empirical evidence that women—including professionals in highstakes business careers—choose to negotiate somewhat less often than do men in such important areas as salary and promotion. In negotiation style terms, women behave, on average, a bit more cooperatively than men. In a study conducted at Carnegie Mellon University’s business school, Professor Linda Babcock discovered that the difference between the starting salaries women MBA graduates were getting and the salaries men were offered (roughly a $4,000 difference in favor of the men) could be accounted for by one single behavioral fact: 57 percent of the men asked for more money after receiving an initial offer whereas only 7 percent of women asked for more. Those who negotiated—both women and men—received an average of $4,053 more than those who did not. Babcock’s research, summarized in her book, Women Don’t Ask, confirms this tendency across a number of studies and contexts. Students in my negotiation classes have added another item to the list of practices women tend to follow more than men: they rely heavily on “fairness” arguments, assuming their counterparts will be responsive to their reasoned, relationship-friendly methods. These tactics can pay off, of course, but only when other parties are tuned to the same relationship wavelength. The experience of one of my students, Marci, vividly illustrates exactly how the gender factor can subtly work its way into the bargaining process. Prior to starting her MBA studies, Marci worked for a midsized computer services firm and was the only female in her unit. Consistent with Babcock’s research, Marci had not negotiated her offer when she received it from her new employer. In fact, she was simply delighted to get the job. After a couple of years of exemplary work, she gradually became responsible for business representing 30 percent of the company’s revenue—while two better-paid male counterparts who started work with her were handling projects worth only 1 percent of revenues each. She thought she deserved a raise. Her method of introducing the raise issue was characteristically indirect, however. She went to her boss and requested a performance review. “I thought it was a great way to get my superiors to notice my success without blowing my own horn,” she told me during class. “I did not want to appear pushy.” Her tactic did not work. The boss could not find the time to review her. Many women might stop here, but Marci was persistent. She went to the president of the company and boldly asked for a 20 percent raise, arguing that her male coworkers were getting 20 percent more pay but managing fewer people and projects. Thus, a 20 percent raise was “fair.” This, too, failed. As she described it, “I kept repeating, ‘This is not fair.’ In retrospect, fairness required even more than a 20 percent salary increase based on my contribution, but I was not confident enough to ask. No doubt, this insecurity shined forth.” In addition, as she put it, “given that I was working such late hours, seemed so committed to my position, and appeared to have no inclination to look for another job, there was no urgent necessity to listen to me.” In the end, Marci got her raise—just in time for her to turn it down. When the company discovered that she had been accepted into Wharton’s MBA program and intended to go, it offered her a 35 percent raise. But by this time, Marci was already out the door. As she told her fellow students, “Being afraid to ask is the most self-defeating trait a woman can have. Don’t be afraid to look pushy.” The second gender-based research finding I find persuasive has to do with stereotypes. Because women appear, on average, to be somewhat more cooperative than men, both men and women bring stereotypes to the bargaining table that exaggerate this difference, creating self-fulfilling prophecies and blinding them to what is really going on. This can work either to women’s disadvantage oradvantage, depending on the experience of the negotiator. For example, studies have shown that women bargain less effectively when they are reminded of a negative, women-are-wimps gender stereotype just prior to a transaction. It seems that fear of being stereotyped as a passive female can sabotage a woman’s confidence and hence her ability to effectively use her own style, whatever that style may be. Even attempts to prove the stereotype wrong seem to backfire, leading to overly aggressive behavior and less-than-stellar results. This psychological process is reversed if women are given a positive, women-are-collaborative stereotype just prior to negotiating. Now the self-fulfilling prophecy creates a good bargaining experience and better results. But because the actual stereotype in the world is more often negative than positive, women sometimes suffer from what scholars call “stereotype threat.” On the other hand, skilled manipulation of others’ stereotypes regarding women can give a female negotiator a significant advantage if she plays her cards right. This ability to turn the tables on opponents seems to come with experience. A top-ranked woman negotiator once spoke to our class about her adventures representing distressed companies in “work-out” situations. These hard-nosed negotiations take place between creditors and companies that cannot pay their bills. Potential bankruptcy forms the backdrop to the bargaining. Few women make this their professional calling, and our speaker reported that her femininity was almost always an asset in this tough arena. “For example,” she said, “whenever a guy on the other side of the table attacks me personally, I never speak up to defend myself. I wait for a man on the other team to come to my defense—one always does—and then I have gained an ally and divided their group. It’s an advantage.” Another speaker, a petite woman who was head of mergers and acquisitions for a major pharmaceutical company, reported that she liked to play with stereotypes of all kinds. She was born in Poland but moved to Israel as a child. “Before a negotiation,” she explained, “I always find a way to make it known that I was once an Israeli military officer. I create the impression that I am going to be tough as nails, and then I go in and melt their hearts. They are so relieved—and they work with me. Of course, I can always fall back on that first impression if I need to.” Gender does not have to become an issue in negotiations. But smart negotiators try to anticipate every aspect of their own and their counterparts’ behavior as part of a good preparation. They also need to be aware of their own assumptions. Gender differences are therefore well worth considering as part of a complete style analysis. A WORLD OF DIFFERENT CULTURES If gender can complicate the negotiation process, cross-cultural issues can be showstoppers. At the Wharton School, we used to have a small, specialized program in “international business.” Now the entire MBA program focuses on global business problems. And in doing global deals, sensitivity to issues of language, customs, social expectations, and religion can mean the difference between a successful long-term business relationship and a short-lived, unprofitable transaction. Consider the following examples: A British CEO once told me about his first negotiation in Lebanon. He started the negotiation well, but every time he made a concession, the other parties escalated rather than reduced their demands. After several rounds of this over a couple of months, he quit, telling his counterparts that he was thoroughly disgusted with their tactics and that he wanted nothing to do with them. A few days later, they called, saying that they now had “serious” proposals to put to him. He rejected the overture. Aweek later, they called again, making several concessions they had previously said were absolutely impossible. He reiterated that he had no interest in further dealings. At this point in his story, he looked at me ruefully. “The whole thing was really my own fault,” he said. “I later learned that walking away from the table is a very common way to show you are serious in that part of the world. If I had walked out two months sooner, they would have behaved better and I probably could have closed the deal.” Culture can also affect decisions about who should be at the table. For example, different cultures have different sensitivities regarding the status of people at the bargaining table. Some formal cultures require participation by people of equal rank. Other, less formal cultures use functional knowledge and decision authority as criteria for picking negotiators. Such differences can lead to serious breakdowns and misunderstandings. A female attorney working for a prestigious New York law firm once accompanied the male CEO of a major client to Latin America to negotiate a complex deal. Soon after they arrived, the head of the prospective Latin American partner suggested that he and the CEO go off together to discuss business—while his wife and the lawyer go shopping. The lawyer was outraged, assuming this to be a blatant example of Latin American gender bias. Before voicing her objections, however, she called a colleague back in New York, who told her that he, too, had been excluded from preliminary talks during his last negotiation in that country. The Latin American executive was just looking for a diplomatic way to get her out of the picture as a lawyer, not as a woman. It was the local practice, the colleague suggested, for lawyers to negotiate only with other lawyers, not with the businesspeople. Had the woman attorney insisted on participating, she would have soured the deal and destroyed her credibility. These and countless examples like them confirm that culture presents a veritable minefield of stylistic differences in negotiation. The Arusha people gathering under their shade trees in Africa may engage in a process similar to the one business moguls use in New York, but the tone, pacing, signals, cues, and underlying assumptions about relationships can be radically different. Because our global economy depends on bridging these cultural divides, entire books (some of which I list in the bibliography) detail the pitfalls, opportunities, and customs that characterize negotiating in every commercially important region in the world. I will be referring to a variety of different cultural practices throughout the book, especially in the chapters dealing with relationships, exchanging information, and bargaining. For now, I simply want to flag two important points. First, cultural issues usually have more to do with form than substance. That is, they add complexity and potential misunderstanding to the way people communicate with one another, but money, control, and risk are still likely to be the most important issues on the table regardless of what country you are in. And the best way to avoid miscommunication is to do your homework on the culture in question, hire skilled interpreters, and use cultural liaisons to help you avoid cross-cultural meltdowns. Second, the single most important difference in cross-cultural negotiations—other than the obvious problems of language and custom—is the way the parties perceive the relationship factor. As I will detail in the chapter on information exchange, North Americans and northern Europeans tend to focus more quickly on the transactional aspects of the deal, whereas most Asian, Indian, Middle Eastern, African, and Latin American cultures focus more intently on social, relational aspects. As a Japanese MBA student of mine once put it, “Japanese people tend to think of negotiation as a process leading up to an ‘arranged marriage.’ And they behave as if they really are in such a situation.” Westernnegotiators doing business in Japan or other relationship-based cultures do well to approach preliminary social events in this spirit. Cultures may vary in the degree of formality they associate with prewedding festivities, but families in all cultures use these events to thoroughly size up and woo their new, would-be relations. If you want to be successful negotiating in a relationship culture, therefore, be patient and realize that the contract (if one comes) is just one part of a much bigger picture. Beyond Style—to Effectiveness The best negotiators exhibit four key habits of thought that everyone, regardless of their style, gender, or culture, can adopt to improve their negotiation results. They are: • A willingness to prepare • High expectations • The patience to listen • A commitment to personal integrity A WILLINGNESS TO PREPARE HIGH EXPECTATIONS • Research on negotiation reveals a striking fact: People who expect more generally get more. • The goal of an effective negotiator is to have expectations that are high enough to present a real challenge but realistic enough to promote good working relationships. THE PATIENCE TO LISTEN The best negotiators follow this practice: They ask questions, test for understanding, summarize discussions, and listen, listen, listen. A COMMITMENT TO PERSONAL INTEGRITY Effective negotiators are reliable. They keep their promises, avoid lying, and do not raise hopes they have no intention of fulfilling. YOUR BARGAINING STYLE: A CHECKLIST • Understand your bargaining instincts, including how family, gender, and culture have shaped your preferred styles. • Acquire a willingness to prepare. • Set high expectations. • Have the patience to listen. • Make a commitment to personal integrity. CHAPTER 2 - The Second Foundation: Your Goals and Expectations Goals: You’ll Never Hit the Target if You Don’t Aim To become an effective negotiator, you must find out where you want to go—and why. That means committing yourself to specific, justifiable goals. It also means taking the time to transform your goalsfrom simple targets into genuine—and appropriately high—expectations. What is the difference between a simple goal and something that has matured into a genuine expectation? Basically one thing: your attitude. Goals are things we strive toward that are usually beyond the range of our past achievements. Such things as investment goals, weight loss goals, and athletic goals are typical. We set goals to give ourselves direction but we are not greatly surprised or disappointed if we fall short. An expectation, by contrast, is a considered judgment about what we can and ought reasonably to accomplish. If we fall short of our expectations, we will feel sincere loss and disappointment. It will hurt. We may set a goal of having our children attend an Ivy League college, but we have an expectation that they will attend college somewhere. Our expectation about college affects the way we communicate about the subject with others, including our children. They begin to share our assumption that college is in their future, and their behavior reflects that assumption. And guess who in fact expects to go to college? Kids of parents who went to college. The same pattern holds all the way up to the children who expect to obtain doctoral degrees. So it is with negotiation. Our goals give us direction, but our expectations are what give weight and conviction to our statements at the bargaining table. We are most animated when we are striving to achieve what we feel we justly deserve. What you aim for in negotiations often determines what you get. Why? The first reason is obvious: Your goals set the upper limit of what you will ask for. You mentally concede everything beyond your goal, so you seldom do better than that benchmark. Second, research on goals reveals that they trigger powerful psychological “striving” mechanisms. Sports psychologists, salespeople, and educators alike confirm that setting specific goals motivates people, focusing and concentrating their attention and psychological powers. Third, we are more persuasive when we are committed to achieving some specific purpose, in contrast to the occasions when we ask for things half-heartedly or merely react to initiatives proposed by others. Our commitment is infectious. People around us feel drawn toward our goals. Goals Versus “Bottom Lines” Most negotiation books and experts emphasize the importance of having a “bottom line,” “walkaway,” or “reservation price” for negotiation. Indeed, the bottom line is a fundamental bargaining concept on which much of modern negotiation theory is built. It is the minimum acceptable level you require to say “yes” in a negotiation. By definition, if you cannot achieve your bottom line, you would rather seek another solution to your problem or wait until another opportunity comes your way. When two parties have bottom lines that permit an agreement at some point between them, theorists speak of there being a “positive bargaining zone.” When the two bottom lines do not overlap, they speak of a “negative bargaining zone.” This is what happens when a buyer does not have enough money in his or her budget to meet a seller’s minimum acceptable price. A well-framed goal is quite different from a bottom line. As I use the word, “goal” is your highest legitimate expectation of what you should achieve. For example, in the case of the used CD player, the seller has a bottom line of getting at least $100, but the seller might set a goal of $130 based on the prices paid for similar CD players in used equipment stores. If setting goals is so vital to effective preparation, how should you do it? Use the following simple steps: 1. Think carefully about what you really want—and remember that money is often a means, not an end. 2. Set an optimistic—but justifiable—target. 3. Be specific. 4. Get committed. Write down your goal and, if possible, discuss the goal with someone else. 5. Carry your goal with you into the negotiation. Note: Optimistic goals are effective only if they are feasible; that is, only if you believe in them and they can be justified according to some standard or norm. CHAPTER 3 - The Third Foundation: Authoritative Standards and Norms A Psychological Fact: We All Want to Appear Reasonable Why are standards and norms—particularly standards the other side has adopted—such an important part of bargaining? Because, all else being equal, people like to be seen as consistent and rational in the way they make decisions. Psychologists have a name for this need-to-appear-reasonable phenomenon. They call it “the consistency principle.” Social psychologists have discovered that people have a deep need to avoid the disjointed, erratic, and uncomfortable psychological states that arise when our actions are manifestly inconsistent with previously expressed, long-held, or widely shared standards and beliefs. Most of us have complex “consistency webs” that are interconnected at many levels of our personality. Because we like to keep these webs intact, we rationalize our actions so they appear (at least in our own eyes) to be consistent with our prior beliefs. We are also more open to persuasion when we see a proposed course of action as being consistent with a course we have already adopted. Negotiations are fertile ground for observing the consistency principle at work. Whether we are aware of it or not, we sometimes feel a tug to agree with the other party when the standards or norms he or she articulates are consistent with prior statements and positions we ourselves have taken. We also feel uncomfortable (though we may keep this to ourselves) when the other side correctly pointsout that we have been inconsistent in one of our positions or arguments. In short, standards and norms are—or can be—more than just intellectual pawns in bargaining debates. They can be strong, motivating factors in the way negotiations proceed. The Consistency Principle and “Normative Leverage” The consistency principle can give you what I call normative leverage in negotiation. Normative leverage is the skillful use of standards, norms, and coherent positioning to gain advantage or protect a position. You maximize your normative leverage when the standards, norms, and themes you assert are ones the other party views as legitimate and relevant to the resolution of your differences. If you set up your own needs, standards, and entitlement as the only rational approaches to a negotiation, you will not inspire agreement. Instead, you will have a fight on your hands pitting your principles against the other party’s. The best practice is therefore to anticipate the other side’s preferred standards and frame your proposal within them. If you cannot do this, prepare to argue for a special exception to his standard based on the special facts of your case. Attack his standard only as a last resort. Beware of “Consistency Traps” Skilled negotiators know about the human need to appear consistent and try to use it as often as they can. Truly manipulative people go beyond identifying their counterparts’ standards for positioning purposes and try to trick their opponents by using what I call consistency traps. The goal of a consistency trap is to precommit you to a seemingly innocent standard and then confront you with the logical implications of the standard in a particular case—implications that actually turn out to run against your interests. This is a form of intellectual coercion, and you should be ready to defend against it. Collection agencies, credit card companies, and high-pressure sales companies routinely use consistency traps as part of the scripts they give telemarketing people to read on the telephone when they call you at dinnertime. You can learn to see a consistency trap coming if you know what to look for. The tip-off is when the trapper tries to get you to agree with some statement before telling you why the statement is important. “Would you like to save some money?” says the long distance company telemarketer. “Sure,” you reply. Snap! The trap closes. “Our records of your monthly phone usage indicate you will save more than one hundred dollars by switching to our service. How about starting to save right now?” You are logically committed to saying “yes.” You have to invent some new reason or excuse to say “no,” and the telemarketing company has a well-rehearsed answer for them all. At the bargaining table, consistency traps are a favorite of aggressive, competitive negotiators. The pattern is the same as that used by telemarketers. Manipulative negotiators try to get you committed to a relatively innocent-sounding principle or standard (“A fair price for this company should reflect comparable sales of like companies, don’t you think?”), then spring their trap by arguing that yourbargaining position violates the principle you just endorsed (“Your proposed selling price is 30 percent more than the comparable sales you just agreed should be the benchmark”). How can you defend against consistency traps? By being alert to them. When the person you are negotiating with begins asking leading questions before you know where he is going, slow the pace. Turn the tables on the trapper. Elicit as much information as possible about why these questions are important before committing to anything. If you are nevertheless pressed into agreeing to a standard, qualify it or phrase it in your own words and use the broadest possible terms, leaving ample room for interpretation later. “I believe comparable sales may be relevant to our discussions, although I am not sure just what time frame or industries we should be looking at,” you can say to the competitive negotiator. “Why don’t you show me all your data?” Even with these precautions, locking horns with a determined consistency trapper can be uncomfortable and unsettling. You have to be alert to every move he makes. If you are caught in an inconsistency, you have two choices. Either you can adjust your position to conform to the standard that you have admitted applies or you can hold your ground, admitting that you made a mistake when you agreed to the standard. This latter move will cause you to lose some face, but that may be less costly than a bad bargain. Using Audiences Relying on the other side’s standards and norms to frame your proposals is fine, as long as your goals can be positioned within those standards. But suppose they cannot. Suppose the other side’s standard directly contradicts your position and there are no exceptions or interpretations that can save you. Should you attack the standard and try to change the other party’s mind? You can try, but chances are the other party will cling to his beliefs. In these difficult cases, you will need to resort to explicit leverage and search for an ally—a third party to whom your bargaining counterpart is answerable and who is sympathetic to your norms. Once you can locate such a person, you need to arrange things so you negotiate in the third party’s presence or under the third party’s protection. Allies serve as audiences or witnesses to guarantee the application of standards that ought, in fairness, to apply. In essence, you leverage the audience’s consistency principles to bypass the party that opposes your goals. Positioning Themes A final, powerful way the consistency principle operates in negotiations is through what I call positioning themes. A positioning theme is a crisp, memorable phrase or framework that defines the problem you are attempting to solve in the negotiation. Asserting such a positioning theme early in a negotiation helps the other party see why you are there and what overall interests and norms tie your various bargaining positions together. “We’re buying a vehicle to use as a second car at home,” you tell the car dealer. “We want reliability, small size, and a low price.” A good positioning theme not only shows the other party why you are there, but it also helps you keep your eye on your own goals. When the going gets tough and the deadline is approaching, a good positioning theme can hold your bargaining position together just as sturdy ropes and bracing hold together a ship being tossed about by a strong wind. The Power of Authority In addition to the consistency principle, there is a second psychological lever that makes standards and norms persuasive. This is the human tendency to defer to authority. In negotiations, this tendency can affect both the process and the results of an exchange in a number of ways. Standards and norms have power in negotiation in part because they carry an authoritative message about what the market, the experts, or society has determined to be a fair and reasonable price or practice. In addition, most of us occupy a number of social roles in our negotiations, and we may feel a strong need to act in ways that are consistent with our own vision of what these roles require—including being deferential to people and principles that appear to have high status or enjoy broad acceptance. Psychologists have discovered a firm fact about human nature: We are inclined to defer to authority. Some cultures emphasize obedience to authority more than others, but even Americans, who tend to be highly individualistic, defer to authority in many situations. Deferring to authority is useful most of the time. Society would not work well if we spent all our time questioning the boss’s taste in office decor and the various OUT OF ORDER and DO NOT ENTER signs we encounter every day. But authority becomes a problem in negotiation in two instances. First, others may seek to exploit our natural tendency to defer to authority by presenting us with unfair terms wrapped in authoritative packages. Second, our deference to authority sometimes inappropriately interferes with our ability to assert our own legitimate interests. Let’s look briefly at each of these authority problems.Skilled negotiators use a host of ploys to combine the use of standards with our willingness to defer to authority. They present us with dense, authoritative-looking standard form contracts written in unintelligible legalese and resort to other expert talk in explaining what they call the routine aspects of a transaction. Have you ever heard someone you are negotiating with justify their position using explanations based on company policy, standard procedure, and the like? That is a standards-based argument that gains additional power from being combined with an authority ploy. Herb Cohen tells a story in his book You Can Negotiate Anything that illustrates in an amusing way just how easy we are to manipulate based on our deference to authority. Candid Camera, a TV show that uses a hidden camera to observe ordinary Americans reacting to set up situations, once placed a large outdoor advertising sign on the expressway between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the neighboring city of Wilmington, Delaware. The sign read DELAWARE CLOSED. The producers placed a staff member near the sign with a lantern to slow traffic. The hidden camera then recorded people as they went by in their cars. Some people just drove by, ignoring the sign. But others stopped and inquired. The staff member simply referred people to the sign. One dismayed driver even pleaded, “When do you think it will reopen? I live there, and my family is in there!” Such is the power of the printed word—when you print it in billboard-size letters. Next time you are signing a lease you don’t understand or hearing an argument from a supposed “expert” that makes no sense to you, remember this amusing story. The other party may well be telling you that “Delaware is closed,” hoping to trigger unthinking acceptance of his or her unfair or unnecessary demands. Our deference to authority can also needlessly interfere with our ability to initiate negotiations or express our points of view appropriately within organizations. For example, health care workers such as nurses sometimes mindlessly defer to physicians’ judgment in the administration of medicines and carry out orders they know to be nonsense, such as putting eardrops into people’s eyes. Virtually anyone who wears a uniform on the job or works in a hierarchical organization must be constantly alert to the possibility that his or her deference to authority could interfere with the proper discharge of his or her duties. On a more serious note, let me illustrate how our need to maintain consistency with social roles and routines can interfere with our abilities to communicate and, ultimately, negotiate effectively. This tragic example comes from an actual conversation between the captain and copilot of an Air Florida flight departing from Washington, D.C.’s National Airport on a cold, snowy day. The cockpit conversation was recorded by the plane’s “black box” and recovered later, after the crash that terminated this conversation. [The plane is at the gate, awaiting clearance to depart. A heavy snow is falling.] Copilot: See all those icicles on the back there and everything? Captain: Yeah. [Time passes while the plane continues to wait at the gate.] Copilot: Boy, this is a, this is a losing battle here on trying to de-ice those things. It [gives] you a false feeling of security, that’s all that does. [More time passes. The snow keeps falling.] Copilot: Let’s check these tops [wings] again since we [have] been sitting here awhile. Captain: I think we get to go here in a minute. [The plane begins to taxi to the runway.] Copilot [referring to engine instrument readings]: That doesn’t seem right, does it?[Pause.] Ah, that’s not right. Captain: Yes, it is. There’s eighty [referring to an instrument]. Copilot: Naw, I don’t think that’s right. [Seven-second pause.] Ah, maybe it is. Captain: Hundred and twenty. Copilot: I don’t know. [The plane takes off, struggles to gain lift, and then begins to fall into the Potomac River.] Copilot: Larry, we’re going down, Larry. Captain: I know it. [Sound of impact.] The copilot in this example failed to overcome his deference to authority in this situation, with tragic results. Sixty-nine of the seventy-four people on this flight, including the captain and copilot, died. The subsequent government investigation of the accident confirmed that the copilot had been correct—the instrument readings were abnormal and the captain should have aborted the takeoff. Partly in response to this and other incidents like it, some airlines now give their flight crews special training on how to communicate regarding safety issues in more direct, effective ways. If you feel the “deference to authority” tug before initiating a negotiation or before expressing your true views in an ongoing discussion, examine the situation closely before deciding to defer. Make sure your deference or concession is warranted by a basic, interest-based justification, not just your counterpart’s title or position. GAINING NORMATIVE LEVERAGE: A CHECKLIST ✓ Survey the applicable standards and norms. Identify the ones the other party views as legitimate. ✓ Prepare supporting data and arguments. ✓ Anticipate the arguments the other side will make. ✓ Prepare a positioning theme and anticipate the other side’s. ✓ If necessary, consider making your arguments before a sympathetic audience. CHAPTER 4 - The Fourth Foundation: Relationships % If you treat people right, they will treat you right—at least 90 percent of the time. —FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT % Leave a good name in case you return. —KENYAN FOLK SAYING The Norm of Reciprocity % Dr. Alvin Gouldner has described the general obligation of reciprocity as “duties that people owe one another, not as human beings, or as fellow members of a group, or even as occupants of social statuses within the group, but, rather, because of their prior actions. We owe others certain things because of what they have previously done for us, because of the history of previous interaction we have had with them.” % Old school economists often have trouble understanding the role of norms such as reciprocity in exchange relationships. They assume everyone is always out to get the most he or she can from every transaction. Skilled negotiators and businesspeople know better. They understand that stable relationships and reliable interactions based on reciprocity are enormous sources of both economic well-being and personal satisfaction. An ounce of well-grounded personal trust in a business partner is worth a thousand pounds of formal contracts and surety bonds. And being a trustworthy person gains us more than future business. It also gains us self-respect. The “Ultimatum Game”: A Test of Fairness Boiled down to its essence, the norm of reciprocity in negotiation amounts to a simple, three-step code of conduct. First, you should always be trustworthy and reliable yourself. You have no right to ask of others what you cannot be yourself. Second, you should be fair to those who are fair to you. This simple rule sustains most productive bargaining relationships. Third, you should let others know about it when you think they have treated you unfairly. Unfair treatment, left unnoticed or unrequited, breeds exploitation—followed by resentment and the ultimate collapse of the relationship. Let me illustrate just how powerful these three rules are as a “code of fair behavior” in bargaining. Negotiation researchers have repeatedly used a simple experiment to prove how sensitive people are to notions of equity and fairness in their bargaining relationships. It is called the “ultimatum game.” It works as follows. Suppose you are sitting next to a stranger at a bar. Someone comes in and hands the stranger $100, telling the pair of you that, if you can agree on a division of the $100 between you, you can both keep whatever you agree to. Here are the rules: The stranger must make a single offer to you for some number between $0 and $100. You must then either accept or reject that offer—no haggling allowed.If you accept, you split the money as agreed. If you reject, neither of you gets any money. After a first round of play, the stranger will get another $100 and you will play again. Now assume the stranger makes you the following offer: He gets $98 and you get $2. Would you accept or reject? Although $2 is better than nothing, many people in negotiation experiments involving even one round of this game reject this patently unfair division. In fact, some people reject offers going all the way up to 25 or 30 percent of the total amount being divided. Why? Because these divisions are not a “fair” split of the money and by saying “no” people punish the person who has made the unfair offer. True, you lose some money if you turn the $2 offer down—but the other guy loses $98. Many people think it is worth a few dollars to stand up for “fairness.” In a two-round game, our inclination to insist on fairness is bolstered by the fact that our behavior in round 1 affects the way the other party will treat us in round 2. Suppose you accept the stranger’s unfair $2 offer in the first round. Now the stranger (not a stranger any longer) gets another $100. What do you think he will offer you in round 2? Probably $2. But what if you had turned down his first offer? What would his second offer be? Something more than $2—and maybe as much as $50. Your insistence on fairness in round 1 would set the stage for establishing a norm of fairness and reciprocity between you in future rounds. Now imagine that instead of being greedy, the stranger is a fair-minded person who offers you $50. Almost everyone would say “yes” to this. The $50 split is a manifestly fair division and deserves a positive response. You and the stranger could go on playing this game all evening—until the person supplying the money got tired and went home. Finally, suppose the stranger offers you $55 of the $100? You might try to give your generous new friend $5 back to keep your accounts at the “fair” and equal level. But the game does not permit this, so you would have to accept the $55 offer. You would also begin thinking about your relationship with the other person somewhat differently. You would “owe” that person something. The other person now faces the problem of finding a way to reciprocate in kind. If there was no immediate opportunity, he might look out for you as a firm friend well into the future. The lesson to take from these examples of how reciprocity works is straightforward: Just because you have power in a given situation does not mean it is smart to use it. In fact, it may be wiser to use the situation as an opportunity to establish the foundation for a future relationship. Generosity begets generosity. Fairness begets fairness. Unfairness ought to beget a firm response. That’s the norm of reciprocity in relationships. You can also count on the reciprocity norm to help you through the information exchange and concession-making stages of bargaining. Always take turns. After you make a move, wait until the other party reciprocates before you move again. Reciprocity is a reliable guide of proper conduct at the bargaining table. Psychological Strategies for Building Working Relationships 1. THE SIMILARITY PRINCIPLE At the most superficial level, a simple psychological fact is that we tend to trust people who appear more rather than less familiar to us—people who act like us, share our general interests and experiences, and identify with the same groups. 2. THE ROLE OF GIFTS AND FAVORS Another time-tested way to encourage the delicate process of establishing trust in working relationships is to give the other side something as a symbol of good faith. Behavioral economists have argued that gifts—especially gifts between unrelated strangers—often serve as signals regarding intentions to invest in a future relationship. They cite as examples everything from certain animal courtship behavior to gift giving in business mergers. Gifts, kindnesses, and a thoughtful regard for other people’s feelings are all ways of helping to establish and maintain close personal relationships—and the same acts carry symbolic weight at the bargaining table even though the relationships there may be more professional than personal in character. 3. TRUST AND RELATIONSHIP NETWORKS A third way to establish a measure of trust at the bargaining table is through the operation of relationship networks. Such networks often help us gain access to and credibility with those we are seeking to influence. The mere fact that we share a mutual acquaintance with our counterpart may help us appear more familiar and establish a minimal condition for trust. If our counterparts know someone who can specifically vouch for our trustworthiness, this helps them gain even more confidence that we will treat them fairly. Relationship Traps for the Unwary Here are a few common traps to watch out for. 1. TRUSTING TOO QUICKLY Cooperative people assume that most people, like them, are fair and honest. Not wanting to appear greedy or suspicious, they take big risks too early in a bargaining encounter. This can happen when negotiators on the other side ask for substantial sums of money or performance commitments up front without sufficient assurances that they will fulfill their side of the bargain. The solution here is to take your time and build trust step by step. It helps if you can use your relationship network to check the other party out. If this is not possible, take a small risk before you take a big one. See if those on the other side reliably reciprocate in some little matter that requires their performance based on trust. If they pass the test, you have a track record on which to base your next move. 2. RECIPROCITY TRAPS Sharks can manipulate the norm of reciprocity, triggering a feeling of obligation in well-meaning people when none is appropriate. Many of us have experienced this in everyday encounters with various con artists. How about the people at the airport who give you a flower and then ask for a donation to their charity? You try to give them the flower back, but they insist you keep it. You feel angry, but you also feel obligated. This is nothing less than a well-crafted reciprocity trap designed to trigger donations that far exceed the flowers in value. At the bargaining table, watch out for people who make small concessions and then ask for much bigger ones in return. Similarly, beware of those who reveal a little information of their own and then ask you to disclose your entire financial position and cost structure. These are patently unfair exchanges, but the norm of reciprocity is so strongly ingrained in many of us that we respond to the form of the exchange more than the content. Once those on the other side make a cooperative move in our direction, we feel compelled to reciprocate, and we sometimes do not pause to consider whether their suggestion about how to do so is really prudent or appropriate. If you feel yourself feeling pressured to reciprocate when it does not feel quite right, take a break and consider the overall situation before making your next move. Do you really owe the other party something, or are you falling into a reciprocity trap? 3. NEGOTIATING WITH FRIENDS WHEN THE STAKES ARE HIGH As was mentioned earlier, friends and lovers make bad bargaining partners when the stakes are high. People in very close relationships tend to rely on equal-split norms to make divisions. In the $100 “ultimatum game,” they split $50-$50 in round after round. But as many a broken business partnership can testify, very high stakes can bring out the shark in even a close friend or associate. Suppose the ultimatum game involved a final round in which the stakes were raised to $10 million. Your friend now has a choice of what to offer you. Do you think he might be tempted to offer you $1 million or even $500,000, figuring you could not say “no” to that kind of money and deciding that for $9 million he can live without your friendship? It may not say much for human nature, but many people would yield to this enticement. When the stakes rise, people in close relationships are well advised to seek help in negotiating tough allocation issues. Equity norms (such as “To each according to his inputs” or “To each according to her risk”) might become more appropriate division norms than simple fifty-fifty splits. Even if both parties are operating in good faith, equality norms tend to leave large areas of potential value unexplored. Energetic problem solving can sometimes bring these opportunities for gain to light better than simple compromises. Letting relationship concerns overwhelm the negotiation may eliminate these potential gains. When the stakes are high, therefore, it is often wise to delegate the bargaining task to professional advisers. If this sounds too confrontational, finding a single adviser trusted by both sides to act as a mediator or go-between might help. Such neutral parties can ensure that the maximum amount of imagination is brought to the transaction without endangering future cooperation between the principals. THE RELATIONSHIP FACTOR: A CHECKLIST ✓ Gain access and credibility through relationship networks. ✓ Build working relationships across the table with small steps such as gifts, favors, disclosures, or concessions. ✓ Avoid reciprocity and relationship traps like trusting too quickly, letting others make you feel guilty, and mixing big business with personal friendships. ✓ Always follow the “Rule of Reciprocity”: • Be reliable and trustworthy. • Be fair to those who are fair to you. • When other parties treat you unfairly, let them know about it. CHAPTER 5 - The Fifth Foundation: The Other Party’s Interests If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as from your own. —HENRY FORD Given the importance of focusing on the other side’s interests to create opportunities for favorable trades, how should one go about doing so? The following steps will help you focus your attention on what the other party wants and how these interests can be used to advance your own goals. 1. Identify the decision maker. 2. Look for common ground: How might it serve the other party’s interests to help you achieve your goals? Shared interests are the “elixir of negotiation,” the salve that can smooth over the issues which you and the other party genuinely disagree about. The shared interests that are hidden in all negotiation situations are the foundations on which to build your proposals. 3. Identify interests that might interfere with agreement: Why might the other side say “no”? 4. Search for low-cost options that solve the other party’s problems while advancing your goals. CHAPTER 6 - The Sixth Foundation: Leverage Every reason that the other side wants or needs an agreement is my leverage—provided that I know those reasons. —BOB WOOLF You can get much further with a kind word and a gun than you can with a kind word alone. —ATTRIBUTED TO AMERICAN GANGSTER AL CAPONE Leverage: The Balance of Needs and Fears Skilled negotiators pay close attention to the other party’s needs and interests. But let’s be clear: They do so for a purpose. They are not negotiating in order to solve other people’s problems. They are negotiating to achieve their own goals. And the most reliable way to achieve your goals at the bargaining table is to acquire and use something everyone wants but only negotiation “naturals” fully understand: leverage. Leverage derives from the balance of needs and fears at the bargaining table. For all its importance, many people are confused about exactly what leverage is and how to use it. They also have trouble coping with the fact that leverage is a dynamic rather than a static factor in bargaining. It can change moment by moment. The best way to test your own understanding of leverage—let’s call it your “leverage IQ”—is to work your way through an example of a tough, high-stakes bargaining situation, asking yourself each step of the way, “Who has the leverage?” and “Given the leverage situation, what should the parties do next?” If you can understand how leverage works in a concrete situation such as this, you are ready to begin analyzing leverage in your everyday business and professional negotiations. The example I have chosen to introduce the dynamics of leverage involves the kind of crisis that makes even expert negotiators break out in a cold sweat: a hostage taking. Many people feel that negotiating with hostage takers sets a bad precedent, but it is safe to say these critics have not had the bad luck to become hostages themselves. Moreover, as unique as a hostage situation may appear, the leverage lessons learned here apply broadly to any business or personal situation in which one side seems to have complete control and is dictating your moves. As you read the following story, watch carefully as the police authorities gradually take a situation that is totally out of their control and carefully turn it around by developing leverage from three sources: information on what the other party wants (both explicitly and implicitly), the power to make the other side worse off, and norms or values the other side respects. The Hanafi Hostage Situation In March 1977, 12 heavily armed members of a little-known religious sect calling themselves the Hanafi Muslims seized three buildings in Washington, D.C., killing 1 radio reporter, wounding many other people, and taking 134 hostages. The three buildings included the District of Columbia’s city hall, the national headquarters of the Jewish organization B’nai B’rith, and the Islamic Mosque and Cultural Center on Massachusetts Avenue. The leader of the Hanafi Muslims, Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, had recently been the target of a brutal crime himself. Hit men from the largest and most powerful black Muslim group of the day, Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, had broken into Khaalis’s Washington home and murdered five of his children and several women living there. Seven members of the Nation of Islam had been tried for these murders; five had been convicted. But Khaalis was not satisfied. As his group stormed the B’nai B’rith building, Khaalis exclaimed, “They killed my babies and shot my women. Now they will listen to me—or heads will roll!” With the Washington police blockading the three buildings, the Federal Bureau of Investigation called to full alert, and the media streaming in, Khaalis made his demands known to the press. He wanted three things: the immediate removal from all U.S. theaters of a movie starring Anthony Quinn called Mohammed, Messenger of God; the return of a $750 fine imposed against Khaalis for misconduct during the hit men’s trial; and the surrender to Khaalis of the five men convicted of murdering his children. Barricaded in their respective buildings, the Hanafi Muslims continued to terrorize their hostages and announced that they were prepared to die in defense of their beliefs. Let’s stop this news reel here—at a time when the action also stopped for the participants. Assume you are an adviser to the FBI and the Washington police chief. You must decide what to do next. What will it be? Storm the buildings and free the hostages, who are clearly in grave danger? Send for the five Nation of Islam murderers and trade their lives for the 134 hostages? Call the distributor of Mohammed, Messenger of God and tell him to stop the show? Your answer, regardless of what it is, will depend on your understanding of the relative leverage the parties had at this point in their confrontation. Let’s assess the situation. Who Controls the Status Quo? First, it always helps to know who, if anyone, controls the status quo and who is seeking to change it. Leverage often flows to the party that exerts the greatest control over and appears most comfortable with the present situation. Prior to the assaults, the status quo was working against theHanafi Muslims. They were a marginal group at the fringes of the black Muslim movement and drew, at most, casual monitoring from people in power. The hostage taking changed all that. Now the Hanafi Muslims controlled the status quo. In fact, the strategic nature of the Hanafi Muslim action is an important part of the leverage equation. These events were not random acts of violence or botched robbery attempts. Khaalis took the hostages precisely to gain leverage—both to get the attention he craved and to acquire something he could offer in trade. Khaalis was willing to kill others and die himself, but his purpose in taking hostages was neither murder nor suicide; he sought hostages as leverage to achieve specific goals. So the Hanafi Muslims gained at least a temporary advantage by seizing control of the status quo. Now what? Both sides were heavily armed; both could harm each other by using their weapons. The power to make the other side worse off by taking away things they have—in this case life itself—is an important source of leverage. Threats: They Must Be Credible Threats, sometimes explicit but often implied, are a factor in many negotiations. In fact, the other party will ordinarily sense a threat anytime you suggest an option that endangers its status quo (however they conceive of that important reference point). And using threats in most negotiations is like playing with fire—dangerous for everyone concerned. Tell a union during an employment negotiation that you will not give workers an increase in health benefits, and you may get a spirited objection. Take away an existing benefit of any kind, however, and you risk a full-fledged labor strike. A second point about threats: They are effective only if they are credible. That means the opposing negotiators must share your assumption that implementing the threat will make them worse off, and they must believe there is a good chance you will carry the threat out. If you yourself would be hurt as much or more than they by carrying out a threat, your threat may lack credibility. Which side in the Hanafi Muslim situation could make credible threats? The Hanafi Muslims demonstrated right away that their threats were credible. They killed one person and wounded many others. But the police had a credibility problem. They could not use their weapons without placing hostages at risk, a step they were unwilling to take given the hostages’ large number and diverse locations. This significantly reduced the police threat leverage. Moreover, the Hanafi Muslims improved their position further by announcing that they were ready to die. At least some of them probably were. Why did this matter? The police weapons did not count if they could not make the Hanafi Muslims worse off. The Hanafi Muslims’ weapons, however, continued to count as the means of both killing the hostages and injuring the police. As if all this were not enough, the police were further hamstrung by a variety of laws related to duress and the use of force that constrain civil authorities in hostage situations and govern both parties in ordinary commercial disputes. The police could not go to Khaalis’s house and take hostages of their own, for example. Nor, for obvious reasons, would a threat about the legal consequences of taking hostages and murdering them be useful. It was too late for that. Finally, moves to make life unpleasant in the buildings by cutting off water and electricity would affect the hostages as much as ormore than the Hanafi Muslims. In short, the police’s ability to make Khaalis worse off was sharply limited. The Hanafi Muslims controlled the status quo and had a definite edge in threat leverage. If your first instinct was to storm the buildings and free the hostages with a SWAT team, think again: The leverage in this situation at this time did not favor the use of force. The police weapons in the Hanafi Muslim situation were helpful in one respect, however. By completely surrounding the buildings the Hanafi Muslims had seized, the police regained a degree of control over the situation. Khaalis gradually became aware that he, too, was a hostage. At one point during the thirty-eight-hour ordeal, Khaalis even requested that the police check his home and make sure his wife and remaining family were alive and well. Overall, given the leverage situation that exists early on in most hostage crises, the best move is a counterintuitive one: You should acknowledge the hostage taker’s power, indicate that you have relinquished control of the immediate situation to him, and, as odd as it may sound, look for opportunities to build a working relationship. For Whom Is Time a Factor? What else can we puzzle out about the leverage dynamics in this situation? Another good question concerns time. Which group had time on its side? Although you might think that time favored the Hanafi Muslims, it did not. Khaalis needed time to deliver his message and figure out where he stood vis-à-vis his goals, but he knew that he could not sustain his control over the status quo forever. Psychologists have discovered a fascinating fact about time in hostage situations: The passage of even a small amount of time makes a huge difference in terms of the life expectancy of hostages. Experienced hostage negotiators report that if hostages live through the first fifteen minutes of an ordeal, their chances of surviving are quite good. Why might this be so? First, time takes a toll on the hostage taker’s “do-or-die” commitment. As one commentator has explained it, “The thought of one’s own death grows tasteless when one has chewed on it for [many] hours.” Second, even if the hostage takers maintain their discipline, they sometimes develop relationships with their captives that make killing them in cold blood harder. It appears that such relationships were formed during a more recent, four-month hostage crisis at the Japanese Embassy in Lima, Peru, which ended in a hail of bullets as 140 police officers stormed the 14 rebels holding 72 hostages in the embassy. During the last moments of the government attack on the compound, the Peruvian agricultural minister reported that his guard pointed a rifle at him, then simply lowered his weapon, turned, and walked away to meet his death. So time favors the police in a hostage situation. But how does one buy time from a nervous religious fanatic such as Khaalis? By establishing a communication link. Khaalis himself took care of the communication link. He had his son-in-law contact an African American television reporter to announce the Hanafi Muslims’ demands. This reporter continued to serve as the messenger throughout the crisis, and the police tape-recorded all their conversations, carefully analyzing them to plot their next moves. Create Momentum: Give Them Little Things With a communication link in place, the police set to work building their leverage position by finding things Khaalis wanted that they could deliver. Note the qualifier “that they could deliver.” One of the trickiest aspects of hostage situations is the unrealistic demands that hostage takers usually make. For example, Khaalis wanted to have the five Nation of Islam hit men who murdered his children delivered to him for execution. The authorities could never comply with this request, so they simply deferred the topic, talking instead about other things they might be able to do. The goal was to make Khaalis feel like a player in the situation—to keep him talking. Khaalis’s agenda, like that of many negotiators, was a mix of explicit demands and implicit needs. His actions and silences spoke as loudly as his words. Beginning with the first few telephone calls, the authorities began to assemble a list of concessions Khaalis might value. To start the ball rolling, the police made a strategic decision to meet two of Khaalis’s demands. First, they arranged for movie theaters around the country to stop showing Mohammed, Messenger of God. Second, an official from the city government delivered a certified check for $750 to Khaalis’s house, a gesture Khaalis’s wife confirmed via telephone. The police used these concessions to buy time and to establish their credibility. Then they probed to see what they should do next. One curiosity was why Khaalis, himself a Muslim, had seized the Islamic Mosque and Cultural Center. As police monitored Khaalis’s telephone conversations, they discovered that Khaalis fancied himself a spokesperson for black Muslims, a role that nobody in the Muslim community acknowledged for him. When Khaalis requested that he be put in touch with the ambassador from Pakistan, an Islamic country, to discuss religious issues, the authorities saw an opening. Joined by the ambassadors from Egypt and Iran, the Pakistani diplomat spoke to Khaalis by phone during the first night and second day about Muslim theology and various religious teachings. The diplomats were impressed with Khaalis’s knowledge. He knew his Koran. More important, the authorities confirmed that Khaalis liked playing the role of Muslim religious leader in front of a distinguished audience. They began to see that Khaalis had revealed an important need when, upon storming the B’nai B’rith building, he had shouted: “Now they will listen to me.” Create a Vision That the Other Side Has Something to Lose from No Deal In a tough negotiation, it is not enough to show the other party that you can deliver things he wants. He will almost always discount this sort of demonstration and raise his demands. To gain real leverage, you must eventually persuade the other party that he or she has something concrete to lose in the transaction if the deal falls through. As the Hanafi Muslim situation developed, the focus of negotiations gradually shifted from the hostages to Khaalis’s interest in Islamic theology as well as his self-image and self-esteem. The authorities wanted Khaalis to realize that his best hope of becoming a black Muslim leader resided in his bringing the crisis to a successful rather than a disastrous close. During the second day of the crisis, Khaalis requested a face-to-face meeting with the Pakistani ambassador on the main floor of the B’nai B’rith building. This caused a stir in the police camp. How to respond? Sending one person alone into the Hanafi Muslim stronghold simply risked adding a high level diplomatic hostage to the ones already being held. The Pakistani ambassador felt he had established a rapport with Khaalis, however, and he was ready to go. Eventually, the police proposed and Khaalis agreed to a meeting with all three diplomatic ambassadors accompanied by two unarmed police officials. This face-to-face encounter was to become a turning point in the negotiation, with the personal integrity and credibility of everyone present placed squarely on the line. The officials sat with Khaalis at a folding table in a first floor corridor. For three hours, the ambassadors and Khaalis discussed Islamic theology, with an emphasis on the role of compassion and mercy in Islamic thought. Then, a little after midnight on the third day of the crisis, the ambassador of Pakistan asked Khaalis to make a gesture of good faith and release thirty hostages. “Why not release them all?” Khaalis asked. That was the breakthrough. As tension eased, discussion turned to the terms of the hostage release. To save face with his movement, Khaalis requested that, after being criminally charged later that night, he be released without bail to await trial at his home. Meet that condition, said Khaalis, and the crisis would be over. This last-minute, unexpected request illustrates nicely how leverage can dictate the last moves in the closing moments of a negotiation. Although Khaalis was clearly at a disadvantage at this point, having signaled his willingness to bring the crisis to an end, his men still had what the authorities wanted—the hostages. With this last move, he offered to give his opponents everything they wanted in return for a relatively small concession. His power to deliver the goods favored him in this trade. Would he give up the hostages if they said “no”? He was not saying. It is a testament to the power of face-to-face human communication that this closing condition sealed the deal. The authorities believed Khaalis would keep his word, and he believed they would keep theirs. Telephone calls to the U.S. attorney general and a local judge secured, after some heated debate, agreement to Khaalis’s condition. The Hanafi Muslims peacefully laid down their arms, and at 2:18 A.M. the hostages walked free. To the surprise and dismay of some, the authorities kept their promise and let Khaalis return to his home that morning to await trial under house arrest. He caused no further trouble, however, and several months later a jury convicted him and his men of murder, kidnapping, and related offenses. Khaalis will be eligible for release from prison when and if he reaches the age of ninety-six. What changes in the leverage equation caused Khaalis to relent? First, in spite of his terrorist bravado, he gradually came to see he had more to lose by pressing ahead to a violent death than by resolving the crisis peacefully. Most hostage takers, particularly criminals who take hostages in a panic when their escape route becomes blocked, come to the same realization. Second, the authorities deftly used the negotiation process to make Khaalis feel his needs were important. He stopped the showing of the offensive movie, at least for several days. Authorities returned the insulting $750 fine. Perhaps most important, the Muslim ambassadors made him feel like a national spokesperson for black Muslims. He began to imagine a future in which he played a meaningful role in the world, even from prison. Meanwhile, the violence of the assault may have sated his rage and need for vengeance. By the time he met with the Muslim ambassadors in the B’nai B’rith building, he had dropped all mention of having his children’s murderers delivered to him. Many people have taken issue with the way the Hanafi Muslim hostage situation concluded. Public officials at the time were particularly critical of the decision to let Khaalis return to his home instead of going to jail the morning after the event, despite the promise made in the B’nai B’rith building. After all, a promise made under such duress can hardly be said to be binding. And failing to put Khaalis in jail set a dangerous precedent. But who can say what incentives reliably prompt would-be hostage takers to refrain from acting, or once they have taken captives, from killing their victims? Events like these may not be subject to the usual rules of precedent. Meanwhile, we know for sure that in this case all but one of the hostages walked out of their buildings thirty-eight hours after the assaults. And the perpetrators went to prison for long terms. The officials charged with making decisions in this confusing and life-threatening situation demonstrated a profound understanding both of the leverage positions they faced and of the negotiation process. The Three Types of Leverage: Positive, Negative, and Normative 1. Positive The first and most common type of leverage in commercial situations is needs-based, positive leverage. Every time the other party says “I want” in a negotiation, you should hear the pleasant sound of a weight dropping on your side of the leverage scales. Your job as a negotiator is to uncover everything the other side wants and to investigate as thoroughly as possible just how urgent are his or her various needs. Donald Trump summed this up nicely once when he said, “Leverage is having something the other guy wants. Or better yet needs. Or best of all, simply cannot do without.” 2. Negative The second type of leverage is negative, or threat-based, leverage. Threat leverage gets people’s attention because, as astute negotiators have known for centuries and psychologists have repeatedly proven, potential losses loom larger in the human mind than do equivalent gains. But a word of warning is in order: Making even subtle threats is like dealing with explosives. You must handle threats with care, or you can hurt yourself. You cannot raise a child without a measure of discipline, but a parent-child relationship based on threats is a failure. The police contained the Hanafi Muslim situation by surrounding the hostage takers with overwhelming force, but their success came in never using it. Moreover, if others use threats against you, you should respond in kind if necessary. Highly competitive people, in particular, sometimes need to hear that you can match their threat power “tit for tat” before they will settle down and negotiate based on the merits of a deal. 3. Normative The third and final type of leverage is normative leverage, which derives from the consistency principle discussed in Chapter 3. This source of leverage played a role in the Hanafi situation in several ways. First, as the Pakistani ambassador drew out Khaalis’s knowledge of and commitment to the Koran, the ambassador laid the groundwork for Khaalis to make a compassionate gesture by releasing hostages. Most religious texts—including the Koran—favor compassion over revenge and love over hate. By the time Khaalis arrived at his fateful moment of decision on the third day of the crisis, the Pakistani ambassador had used passages from the Koran to remind Khaalis that a truly visionary Muslim leader would be a living model of Islamic virtues, not a cold-blooded killer of innocent people. Second, the authorities found themselves in a consistency trap of their own creation by Khaalis’s surprise request to remain at home under house arrest pending trial. The agreement allowing him to do so was the explicit quid pro quo for releasing all the hostages and, even more important, was made after three hours of discussion about the Koran and the meaning of virtue. To have reneged on this promise would have meant, among other things, loss of face for three distinguished Islamic ambassadors who had pledged their word and risked their lives to resolve the crisis. The authorities felt bound in a moral sense to keep their promise even if they had no legal obligation to do so. Leverage is a complex mixture of ideas. It includes opportunities that will be lost if the parties fail to reach a deal, threats to each party’s status quo, and possible losses to each side’s self-esteem should their actions appear inconsistent (in their own eyes) with a prior or professed standard of conduct or dealing. But there is a way to assess leverage in a single, easy-to-remember test: Ask yourself, as of the moment when you make the assessment, which party has the most to lose from no deal. The party with the most to lose has the least leverage; the party with the least to lose has the most leverage; and both parties have roughly equal leverage when they both stand to lose equivalent amounts should the deal fall through. This way of thinking about leverage also points to more sophisticated ways of enhancing your leverage that go beyond just improving your BATNA. Your goal is to alter the situation (or at least the other party’s perception of the situation) so you have less to lose, the other side has more to lose, or both. You can achieve these goals by gaining more information about what the other side really needs,acquiring credible power to make the other side worse off, framing your needs under principles and norms that are hard for the other side to walk away from, binding yourself to a course of action that forces the other side to concede, and, finally, improving your BATNA, that is, seeking alternative solutions to your underlying problem that do not require the other party’s cooperation. The Power of Coalitions One of the most important ways to gain all three types of leverage is by using relationships and shared interests to help you create effective coalitions to support a bargaining position. When you can make common cause with others who share your bargaining priorities, you gain advantage in three important and distinct respects. First, in multiparty situations, group dynamics often favor those who are first to achieve a dominant position in terms of numbers. Research on American juries suggests that the first verdict to gain a majority vote during jury deliberations ends up being the verdict the jury unanimously endorses. The same is true at many business meetings. One person makes a suggestion, another picks it up, and pretty soon it is the consensus even though there may be good reasons for doing something else. You can greatly improve your chances of getting your point of view across to a group if you take the time to assemble a coalition before the meeting starts. That way, your position can gain momentum as the members of your coalition take turns expressing support for their shared goal. Second, coalitions gain power from a psychological phenomenon social scientists call social proof. In ambiguous situations, people take their cues from what other people do. If you are going down a crowded street and you notice some people looking up in the sky, you will probably look up, too. Then the person behind you will look up, and so on. Negotiations can work the same way if the issues being discussed are complex and others tend to look to experts to lead the way. Your coalition can provide the cues that prompt others to follow. Finally, coalitions often improve your leverage by either giving you better alternatives, making the other party’s alternatives worse, or both. For example, American cattle ranchers in the mid-1990s were desperate because beef prices were so low that 85 percent of the ranchers in some areas of the Midwest could have qualified for federal food stamp assistance if they had not been too proud to apply. Their problem? A few giant agribusiness firms controlled the meatpacking and slaughtering industry, and the ranchers had no choice but to sell their cattle to these companies. The ranchers were losing $30 for each calf they sold while the meatpackers made $30 in profit on each calf they slaughtered. The ranchers in North Dakota began digging their way out of this situation when they formed a coalition and started their own meatpacking operation, a cooperative called Northern Plains Premium Beef. When the ranchers competed with one another to sell their cattle to the giant slaughterhouses, they lacked leverage. But by combining with other ranchers and slaughtering their own animals, they gained a way to attract consumer dollars directly to their high-quality, distinctively branded beef. In short, they created an alternative distribution system and, in the process, improved their leverage vis- à-vis both the giant slaughterhouses and the restaurant chains. Cooperatives have been successful in getting contracts from some of the biggest steak house chains in the United States. The big firms are taking notice. Common Misconceptions about Leverage MISCONCEPTION 1: LEVERAGE AND POWER ARE THE SAME THING Not true. Leverage is about situational advantage, not objective power. Parties with very little conventional power can have a lot of leverage under the right circumstances. Let’s look at a couple of examples. The first concerns negotiating with small children. Assume you are the father or mother in a household with a five-year-old daughter. The menu this evening features one of nature’s healthiest foods, broccoli. Your daughter does not want to eat it. “Eat your broccoli, dear,” you say sweetly. Your daughter looks you in the eye and says, with emphasis, “No! I hate broccoli!” Who has the leverage? You may be big, rich, powerful, and strong, but your daughter has a lot of leverage in this situation. Why? Because she and only she can eat the broccoli. She controls what you want and, at the moment, has nothing to lose by saying “no.” And that isn’t all. She probably senses that the issue is important to you. That improves her position. You may be willing to offer something for her cooperation. This critical leverage insight can apply just as readily to negotiations with stubborn politicians, cranky customs officials, and tightfisted budget officers as it does to children. Regardless of how important you are, you had better treat such people with care when they control the decision you want made. But back to the dinner table. What can you do about the broccoli? You could try reasoned persuasion, but your daughter is not likely to care much about nutritional standards. So whatevernormative leverage you may have will not be worth much. Another option is to offer your daughter bribes to encourage her cooperation. Concrete offers of things she likes such as desserts or treats may create attractive visions in her mind. She would lose these delights if negotiations were to break down. The promise of treats might gain you some leverage. However, parents everywhere know that using this form of leverage with children carries risks. Bribing your child to do things she should be doing anyway eventually spoils her, making your life difficult, not easy. How about resorting to explicit threats, such as spanking her, sending her to her room, or eliminating dessert from the menu? Your size and vocal power make it easy to use threats, but it is risky to do so over an issue like broccoli. If she complies based on your threat, you will pay a price. She will eat her broccoli as slowly as she can, with periodic grim looks in your direction. A participant in the Wharton Executive Negotiation Workshop once told me his child took four hours to eat his dinner one night after he tried the threat strategy. Dinner turned into a contest of wills. Worse still, suppose she calls your bluff and forces you to carry out your threat? You send her to her room, but she still has not eaten the broccoli. You must then either escalate the dispute even further or concede defeat. Conclusion? Your child may look small and weak in terms of conventional power, but she has leverage in this situation. Your solution should therefore acknowledge your child’s preferences in some way—either by giving her a choice of another healthy vegetable, compromising on the amount of broccoli, adding a sauce, or serving the broccoli in some heavily disguised form. You will do better as a parent if you recognize your child’s leverage in this situation and frame your strategy to address her interests in some way, particularly her interest in feeling like she controls decisions that affect her. You will also do better as a professional if you take the same approach with the stubborn politicians, customs officials, and budget directors who control implementation of things you want done at work. So leverage is not the same thing as conventional social or economic power. Examine the specific situation you face and ask: What do I control that the other side wants, what do they control that I want, and who stands to lose the most if no deal gets done? Don’t make assumptions about leverage based on wealth or position. MISCONCEPTION 2: LEVERAGE IS A CONSTANT THAT DOESN’T CHANGE Wrong. Leverage is dynamic, not static. Leverage changes as negotiations proceed. Some moments are therefore better than others for making your needs known and insisting that they be met. All this may seem obvious, but many very smart people fail to understand the relationship between time and leverage. For example, there is a “golden moment” when job hunters should negotiate for extra benefits such as relocation expenses, bonuses, and company cars. That moment comes after they get an offer from a firm but before they accept the offer. During this peak leverage interval, the employer has explicitly committed itself, but the prospect is still free to say “no.” This puts the employer at a potentially greater risk of loss than the prospect, improving the prospect’s position considerably. As compared with the period before the offer is made or the period after the prospect has said “yes,” this golden moment is the time when an employer will give maximum attention to a prospect’s special needs. Of course, there are no guarantees the employer will agree to sweeten a deal, even at the golden moment. The employer still controls its job, and, in any given case, the prospect may have more to lose if the offer falls through. But timing matters in every leverage analysis. You improve your chances of success if you ask for things when your leverage is at its height. MISCONCEPTION 3: LEVERAGE DEPENDS ON THE FACTS Incorrect. Leverage is based on the other party’s perception of the situation, not the facts. When Joshua won the Battle of Jericho in the Bible, he did it with a few cymbals and some torches, not a mighty army. The leaders of Jericho surrendered based on their perception that they had a lot to lose. In the Hanafi Muslim example, Khaalis surrendered when he was treated like a Muslim leader even though he wasn’t one in fact. And the police made a prominent display of their weapons around the hostage buildings even though they could not use them. In short, you have the leverage the other side thinks you have. If the other party thinks you are in a strong position, you are—at least for the moment.But the perceptual nature of leverage can also work against you. You may mistakenly assume the other party is stronger than they really are. You may also be in a good position, but the other side may not believe you. In such cases, you must find ways of proving your worth, importance, or power. Some things, such as your ability as an employee or your product’s true value to a customer, are hard to prove. If so, you may need to give away some of your time as a low-paid intern or volunteer to prove your worth or offer some free samples of your product to prompt a later sale. On the negative side, you may need to make a subtle demonstration of your ability to affect the other side’s status quo. It is up to you to see that the other side understands the true leverage situation before it acts unwisely based on a miscalculation. A LEVERAGE CHECKLIST ✓ Which side has the most to lose from no deal? ✓ For whom is time a factor? ✓ Can I improve my alternatives or make the other party’s worse? ✓ Can I gain control over something the other party needs? ✓ Can I commit the other party to norms that favor my result? ✓ Can I form a coalition to improve my position? PART II - THE NEGOTIATION PROCESS CHAPTER 7 - Step 1: Preparing Your Strategy The Psychological Foundations of Negotiations The Four Stages of Negotiation Imagine you are approaching a traffic intersection in your car. You notice that another car is nearing the intersection at the same time. What do you do? Most experienced drivers start by slowing down to assess the situation. Next, they glance toward the other driver to make eye contact, hoping to establish communication with the other person. With eye contact established, one driver waves his or her hand toward the intersection in the universally recognized “after you” signal. Perhaps both drivers wave. After a little hesitation, one driver moves ahead and the other follows. The four-step process: preparation (slowing down), information exchange (making eye contact), proposing and concession making (waving your hand), and commitment (driving through). Preparation Step 1: Assess the Situation The Situational Matrix QUADRANT IV: TACIT COORDINATION The most rudimentary of all negotiation situations is the one found in the lower-right-hand box: Quadrant IV, “Tacit Coordination.” Quadrant IV is characterized by both low conflict over stakes and a limited future relationship. My example of two drivers meeting at a traffic intersection given above is a Quadrant IV event. There is no need for a collision at the intersection (managed correctly, there is little need for conflict over the space), and the parties are unlikely to see each other again (the future relationship is not a factor). Tacit Coordination situations do not call for negotiation so much as tactful avoidance of conflict. QUADRANT III: TRANSACTIONS Now move left to Quadrant III, “Transactions.” These are the situations in which the stakes matter substantially more than any future relationship. House, car, and land sales between strangers, business acquisitions in which the incumbent management will be thrown out after the purchase, and many other market-mediated deals are typical Transactions. It is tempting to think of Transactions as simple “haggling” or “winner-take-all” events in which the relationship between the parties is irrelevant. Transactions can be this simple, but often they are not. The bargaining situation itself usually creates the need for a form of working relationship between the negotiators if they are to close the deal. In the West, this relationship is often limited to mere civility unless the negotiators are professional agents who deal with each other on a repeated basis. In other cultures, a personal relationship (or at least the appearance of one) remains a necessity, even in a Transaction. QUADRANT II: RELATIONSHIPS Our next situation is the exact opposite of Quadrant III. In Quadrant II—the upper-right-hand square —the relationship matters a great deal, and the particular item being negotiated is secondary. This is the Relationships box. Negotiations between couples in healthy marriages, employees working on well-functioning executive teams, and certain kinds of recruitment tasks fall into this category. When relationships are the most important factor, we should strive to treat the other party well, observing careful rules and limits to our bargaining conduct. QUADRANT I: BALANCED CONCERNS The upper-left-hand quadrant is the most interesting and complex of the four situation types. This isthe Balanced Concerns situation. Here, the future relationship and the immediate stakes are in balanced tension with each other. Quadrant I is where many employment disputes, family business matters, partnerships, mergers (in which incumbent management will remain to manage the firm), long-term supplier relationships, strategic alliances, and institutional relationships between different divisions of the same firm are located. You want to do well in these situations but not at the expense of the future relationship. You want the future relationship to be sound, but not at too high a price. Preparation Step 2: Matching Situation, Strategy, and Style Preparation Step 3: Examining the Situation from the Other Party’s Point of View Preparation Step 4: Deciding How to Communicate The fourth step in your preparation is deciding how best to communicate with the other party. There are two important dimensions to this question. First, should you communicate directly with the other side or get an agent involved? If you are a highly cooperative negotiator and find yourself facing off against a bargaining bully, you might do well to hire a hard-nosed agent or lawyer to do your talking for you. Second, if you are going to negotiate yourself, should you communicate face-to-face, by telephone, or by using an electronic medium such as e-mail? If you want to eliminate sales pressure as a factor in buying a new car, decide what car you want and then do your negotiating over the Internet. Because most complex deals these days will inevitably involve some combination of all communication methods, the wise negotiator has a strategy on how best to communicate at each stage of the process. COMMUNICATION ISSUE # 1 : SHOULD YOU USE AN AGENT? The best reason for using an agent is economic: they can sometimes get you a better deal than you could get yourself. But before adding an agent to your team, you should carefully add up the costs that agents bring to the table. These include: • The fee the agent charges. Negotiate this if possible. • The agent’s own agenda. Make sure you know how your agent is compensated and whom he or she is working for. In real estate deals, the listing agent is paid on commission and works for the seller. This has two important implications. First, agents paid on commission usually do better closing a high number of transactions rather than maximizing each and every one. Indeed, research shows that when agents sell their own homes, they leave them on the market longer than when they are selling yours. In addition, be careful how much you reveal to your agent about your true bottom line. Agents working on commission may be tempted to negotiate to your bottom-line level more quickly than you would to get the deal closed. The opposite is often true of an agent paid by the hour. Like the lawyer whorepresented the buyers in our Philadelphia home sale, an agent punching a time clock may drag out the engagement to increase the fee. • Bad feelings. Sometimes agents get into pointless fights, spoiling the relationship between the principals. Lawyers can be “deal breakers” instead of “deal makers” by battling over clauses neither party cares about, creating bad feelings, tensions, and mistrust. If your agent misbehaves in this way, show him or her the door and get the process back on track yourself. • Miscommunication. Whenever you add layers to a communication process, you increase the risk of honest misunderstanding. And when both sides are using agents, the distortion risk escalates. If you want to get an important message to another party and must work through his or her agent, either ask for a direct meeting with the agent present or put your message in writing. • Self-serving bias. Real estate agents are confident they can sell your house, and lawyers are sure they will win your case. Research shows that agents often suffer from overconfidence in their own abilities, leaving you with the problems when they are proven wrong. Do your own research and get second opinions whenever possible. • Time. An old saying goes: “If God had had an agent, He would still be creating the earth.” Using agents creates delays that can prove costly, especially if time is of the essence. COMMUNICATION ISSUE #2: PERSON-TO-PERSON, TELEPHONE, OR E-MAIL? Benefits of using e-mail: • Convenience when parties are at a distance • Time to consider one’s next move • A clear record of the proposals • Ease in conveying large amounts of data to back up proposals • Leveling of the playing field between negotiators with different levels of seniority and experience • The power to quickly mobilize large coalitions of like-minded people using group e-mail lists ~ ~ ~ Because electronic communication is so temptingly convenient, it is especially important to be aware of its pitfalls. Researchers have confirmed these problems repeatedly in experiments. These include: • Increased risk of impasse. Lacking voice tone, facial expression, and conversational pauses, electronic messaging comes across as more aggressive and “in your face” than spoken words. This can trigger reactions in the receiver, who then fires off an angry response. The problem escalates from there. Several detailed studies of e-mail negotiations have confirmed this problem. One pitted MBA students at Stanford and Northwestern University against each other. Half the students were given only their counterpart’s name and e-mail address before starting the negotiation. The other half were given a photograph of their opponent and explicitly instructed to exchange social information on hobbies, families, job plans, and hometowns prior to beginning the negotiation. Ninety-four percent of the “schmoozing” groups had no trouble reaching a deal, while only 70 percent of the “strictly business” groups managed to complete the negotiation. • Careless clicking. The informality and privacy of sitting in front of a computer screen tends to put us off our guard, and we forget that our message can easily be copied and sent to unintended audiences. A former student of mine once made the mistake of negotiating his salary using e-mail. His message arguing for a raise came across as arrogant, and he appeared to be taking too much credit for projects others had contributed to. The e-mail circulated widely throughout the leadership group in his company, and he ended up being fired. • Delay. Research on electronic communications shows that the same problem can take much longer to solve using e-mail than using face-to-face or voice communication. The narrower the pipeline of communication, the longer it takes to get information through it. Delay and associated misunderstandings are special problems when it comes to using email to resolve disputes, as opposed to constructing deals. • Polarized decisions in groups. When groups negotiate electronically, they tend to reach decisions that are more extreme in one direction or another than when they meet face-toface. The lack of social awareness and non-verbal channels for communication seems to reduce our tendencies to compromise. CHAPTER 8 - Step 2: Exchanging Information Let’s look more carefully at the three main functions of the information exchange stage of negotiation: (1) establishing rapport, (2) determining interests, issues, and perceptions, and (3) signaling expectations and leverage. As we do, remember that this preliminary phase of negotiation is often the most overlooked part of the process. Awareness of it therefore yields significant competitive advantages. The Similarity Principle Social psychologists have confirmed Steve Ross’s (and many other expert negotiators’) instincts about the right way to start a negotiation. Psychologist Robert Cialdini calls this the “liking rule.” As he puts it, “We most prefer to say yes to the requests of someone we know and like.” Underneath the liking rule is something even more basic: We trust others a little more when we seethem as familiar or similar to us. Studies ranging over the past thirty-five years have consistently shown that people like other people more when they display appearances, attitudes, beliefs, and moods that are similar to their own, provided that these similarities reflect well on them. These similarities do not have to go deep to smooth the way to better communication. Indeed common affiliation or membership in a given group such as a club, religion, college alumni body, or even nationality (when in a foreign country), is sometimes enough to induce a momentary feeling of relatedness and similarity. And that momentary opening may be all that is needed to establish rapport. Nor does it matter much that both sides know the other is presenting similarity information solely for the purpose of establishing rapport. Even forced prenegotiation “schmoozing” (such as sharing information about the other party such as their images, hobbies, likes and dislikes) reduces the risk of impasse. I am a specialist in negotiation, and I still succumb to the influence of similarity information when someone tactfully opens a discussion with me by telling me about some shared experience, affiliation, or common acquaintance. The similarity principle is a compelling force in human psychology, much like gravity in physics. Rapport Pitfalls: Over- or Underdoing It To repeat: Establishing rapport will not and should not gain one side a significant bargaining advantage over the other. If you sense that your counterpart is trying to extract concessions from you on the basis of his or her initial success in establishing rapport, alarm bells should go off. You are being conned, not negotiated with. We walk a fine line in the rapport stage of information exchange. Most of us know when we negotiate that other people want things from us. We therefore guard against and discount techniques such as flattery and social niceties designed to gain influence. Overt, manipulative, and ingratiating behavior does not usually work and can be very costly in terms of credibility. At the other extreme are blunders at the beginning of a negotiation that needlessly upset or offend the other party. These are especially common in cross-cultural situations, although any thoughtless act can interfere with bargaining. To summarize: Establishing rapport at the outset of negotiations is a distinct, separate part of the information exchange process. Everyone, no matter how simple or sophisticated, likes to be acknowledged on a personal level. The more genuine this personal acknowledgment is, the more effective it will be. Purpose 2: Obtaining Information on Interests, Issues, and Perceptions The second major task in the information stage is obtaining basic information regarding the other party’s interests, issues, and perceptions. Who are they? Why are they here? What is important to them? What are they prepared to negotiate? What is their view of the situation? Do they have authority to close? This aspect of information exchange is important in all negotiating situations, but the higher the stakes, the more care you should take to acquire answers to these questions. Determining interests and issues builds on the preparation work you did using the Six Foundations and analyzing the Situational Matrix. In effect, the information exchange stage allows you to test the hypotheses you developed earlier about the other party’s needs and arguments and communicate your own basic interests—without giving up anything. Probe First, Disclose Later The research on negotiation effectiveness repeatedly underscores a simple fact about skilled negotiators: They focus more than average negotiators do on receiving, as opposed to delivering, information. As I suggested in Chapter 1 when I identified listening as a key effectiveness factor for the skilled negotiator, the best practice in this stage of negotiation is to probe first, disclose later. The average “blabbermouth” negotiator does it the other way around: He carelessly discloses information first and asks questions later. Look at Table 8.1, reporting the results of a study by Neil Rackham and John Carlisle that monitored the behavior of English labor and contract negotiators engaged in actual transactions. What do skilled negotiators do that average negotiators do not? First, they ask twice the number of questions that average negotiators ask. These questions have a purpose: They are designed to elicit real information (“When can you make delivery?” or “How did you calculate your offer?”). Next, they test their understanding of what the other side has said (“When you say ‘ten days,’ do you mean ten calendar days or ten business days?”). Third, they summarize where they think the parties are in the process (“As I understand it, we have agreed to pay you net ninety days of delivery and you have promised to deliver within seven business days of the date you receive our specifications—is that correct?”). Finally, they listen to all of the other party’s answers. TABLE 8.1 Information-Gathering Behavior as a Percentage of All Behavior Observed THE STRATEGIC NATURE OF INFORMATION EXCHANGE It all sounds so easy. All you need to do is ask negotiators on the other side what is important to them and they tell you, right? Not quite. In negotiation, information—especially information about what people want—is power. If the other negotiator is awake (and you must assume he will be), he will want you to disclose your interests and needs before disclosing his own. Why? Because, as U.S. sports agent Bob Woolf said in Chapter 6, “Every reason that the other side wants or needs an agreement is my leverage—provided that I know those reasons.” Negotiators on the other side will want to find out what you want so they can see if your needs provide them with leverage. The leverage effect of information disclosure often gives the opening stage in negotiations a somewhat comic “you first—no, you first” rhythm. Purpose 3: Signaling Expectations and Leverage FIGURE 8.1 Signaling Leverage SITUATION 1 : YOU HAVE A WEAK HAND If your leverage is weak, I recommend you emphasize the uncertainty that always attends the future. If you are selling something and have no other offers, you can discuss what you will be pursuing by way of additional marketing efforts if no deal happens, or talk about your comfort with the status quo. In short, even if you are in a weak position and have few options, you can still appeal to the other party’s desire to minimize future risk by closing a deal now—and the other side can also save himself the expense of continuing his search for a partner. These are not strong signals, but they can keep the process moving without getting you deeply involved in lies or misrepresentations about your own situation. Some people try to bluff their way through a weak bargaining position by acting in ways that strongly signal strength regarding a deal. A successful bluff can make a great negotiation story, but it is a high-risk strategy. You may, after all, end up with no deal. In fact, experienced negotiators can usually see through ploys of this sort—especially tricks such as the “keep-them-waiting” move. As Leslie H. Wexner, chairman of The Limited, once put it, “The longer they keep you waiting, the more they want the deal.” Unless you are an experienced gamesman, leave the bluffing to others and emphasize the inherent uncertainty of the stronger party’s future if it passes up your offer. If your weakness is obvious and you know that they know, it may help your credibility to personalize the situation as much as possible, arrange for a face-to-face meeting, candidly acknowledge the other side’s power, and proceed on that basis. Finally, when all else fails, you can appeal to the other party’s sympathy. Ask the other negotiator what he or she would do in your position. Give the other party a “blank check” question like “What would it take for you to say ‘yes’?” If the other side responds, you may discover you have more leverage than you thought. SITUATION 2: YOU HAVE A STRONG HAND Suppose you think you have a strong hand—your leverage looks good. What signals should you send to the other side in the information exchange stage? You can either send a firm signal that you have the power to demand a favorable deal and intend to insist on one, or you can show your power, then indicate you intend to be flexible in order to build goodwill for the future. If you have a lot of leverage, but for one reason or another you are willing to be flexible, how should you go about sending that signal? It is the same in any negotiation when you have leverage but choose not to use it. Let the other side know what options you have before you show you are not going to exercise those options. You don’t have to be arrogant about it, just matter-of-fact. You view the transaction as part of a relationship, and people in good relationships do not squeeze every nickel they can out of a situation. They treat each other fairly. Someday it will be the other side’s turn. INFORMATION EXCHANGE: A CHECKLIST ✓ Establish rapport. ✓ Obtain information on interests, issues, and perceptions. Probe first, then disclose. ✓ Signal regarding your leverage. CHAPTER 9 - Step 3: Opening and Making Concessions Tactical Bargaining Questions Question 1: Should I Be the First to Open? % Let’s start with the issue of whether you should open or try to make the other party go first. Many complex negotiations will have lots of issues to discuss, and you may be able to discuss some of them without opening in the sense I am using the word. But there will inevitably come a time when you will have to decide who is going to make the first concrete offer on allocation issues such as price, power, or control. % The “never open” rule is easy to remember—but, like most simplistic approaches to negotiation, it is not always good advice. How can you do better? The answer lies in how much information you have. Being newcomers, you should sit tight and let the other side do the talking. The same is true anytime you don’t know the market value of what you are buying or selling. % If you are well informed about the bargaining range, then you gain an important advantage from opening. When I first started teaching negotiation, I recommended the “never open” rule to my classes. Then one of my better students introduced me to an entrepreneur who had successfully bought and sold literally hundreds of small and medium-sized companies. This man made it his practice to name the first price in every acquisition he did. Being the first to open let him fix the range, he explained to me. I subsequently learned that there is a substantial and persuasive body of research that supports this entrepreneur’s practice. First, by naming the first number, you have a chance to set the zone of realistic expectations for the deal. Your opening often forces the other side to rethink its goals. Second, social scientists have discovered a psychological quirk they call the “anchor and adjustment” effect. The term refers to a human tendency to be affected by “first impression” numbers thrown into our field of vision. We tend to make adjustments from these often arbitrary reference points. Researchers have found, for example, that most people seeing the string of numbers 8 × 7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 for a few seconds estimate that it yields a very high product. Other people, shown the same string in reverse order—1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5 × 6 × 7 × 8—think the product is much lower. The two products are identical, so why the different estimates? Because we focus on the first three or four numbers and extrapolate; that is, we anchor and adjust. In negotiation, research suggests that people who hear high or low numbers as initial starting points are often affected by these numbers and unconsciously adjust their expectations in the direction of the opening number. Of course, a totally outlandish number may trigger a strong negative reaction that could offset this effect. But there is some power in or draw toward these initial numbers nonetheless. My entrepreneur friend was taking advantage of the opportunity to both lower his opponent’s expectations and use the anchor effect. But note well: He did enormous amounts of research before he made a bid to set the range. Conclusion? Feel free to open if you think your information about market value is as good as or better than your counterpart’s. Otherwise, guard against the anchor effect, then ask the other party to open. Finally, remember that the best protection against making a mistake at the opening is negotiating with someone who cares about his or her relationship with you. Question 2: Should I Open Optimistically or Reasonably? Okay, either you have decided to open—or the other side opened and it is your move. Should you open aggressively with an optimistic request or make a manifestly fair and reasonable proposal? If you are in a Relationship situation, the answer is obvious: A fair or even accommodating opening is the right move. How about a Transaction? Assuming that you have some leverage, the research suggests you should open optimistically. Indeed, a recent summary of more than thirty-four bargaining experimentsperformed between 1960 and 1980 concluded that a hard-line bargaining strategy (open high and concede slowly) is the best approach to transactional bargaining, especially if direct communication between the parties is limited (as may be the case in a home sale or any other transaction mediated by a broker). That sounds persuasive, you may say, but what exactly is an optimistic opening? I define an optimistic first offer as the highest (or lowest) number for which there is a supporting standard or argument enabling you to make a presentable case. Your opening need not be supported by your best argument, just a presentable one. The difference between an optimistic opening and an outrageous one is this: The outrageous opening has no justification whatever to support it. The optimistic opening, by contrast, is a highly favorable interpretation of some standard or reference point. American lawyers are duty-bound when they argue a legal appeal to make every argument on behalf of their client that they can make “with a straight face.” Optimistic openings are like that: You should reach for but not beyond the “straight face” argument. And remember that in some cultures such as South America, the Middle East, and Africa, anything other than an optimistic opening is a serious social mistake as well as bargaining blunder. For North Americans and some Europeans, part of acclimating to these cultures is getting used to making optimistic (and in some cultures outrageous) opening offers in carpet stores, jewelry shops, and bazaars. Bargaining is a form of recreation in these places. Why Do Optimistic Openings Work in Transactional Bargaining? Optimistic openings take advantage of two well-documented psychological tendencies: the contrast principle and the norm of reciprocity. First, let’s examine the contrast principle. If I want you to pay me $50 for something and I open with a demand of $75 (supported by a presentable argument about prices that “others have paid”), my $50 final offer looks reasonable by comparison with my opening. If I had opened at $55 instead of $75, and moved down only five dollars before I stopped, you would be less likely to think you had gotten a bargain. An optimistic (but not outrageous) opening sets the other party up to feel both relief and satisfaction (and thus be more willing to say “yes”) when the realistic settlement range comes into view. If you think the contrast principle does not apply to you, think again. It is used successfully against millions of people every day. Why do car dealerships have a special sales force to sell you things after you buy a new car? Because they know that you are more likely to spend a couple of hundred dollars on extended warranties and service plans just after you have spent $20,000 on a new vehicle than you would be if you shopped for these things by themselves. The same is true of furniture dealers who sell $75 fabric treatments for your new $1,000 sofa and travel agents who push $150 trip insurance policies just after you book a $3,000 vacation. These add-on sales look inexpensive in comparison to the big money you just paid for the thing you really wanted. But they are usually expensive when compared with the alternatives you could find if you shopped for them separately. That is why the dealers don’t want you to leave the store without giving you these strong after-sell pitches. Second, the optimistic opening permits the person making it to trigger the norm of reciprocity. It works like this: Person A makes an optimistic opening; person B rejects it. Person A then moderates his demand by making a significant concession. Person B then feels pressure imposed by the norm of reciprocity to make a reasonable response, or even to say “yes.” Psychologists have found that this “high opening, rejection, then moderation” procedure works for all kinds of requests, not just bargaining demands. In controlled field experiments, scientists have induced people to agree to all manner of things—including volunteering to take underprivileged children on a trip to the zoo, signing petitions, or giving up smoking for short periods of time—simply by asking them for a big favor first, getting a rejection, then presenting the smaller, apparently more reasonable request. The norm of reciprocity induces people to say “yes” much more frequently after they have rejected your first demand than when you open with your modest request. WHEN YOU LACK LEVERAGE The first exception concerns leverage: Don’t open optimistically if you lack leverage and the other side knows it. If you are a new college graduate applying for an entry-level position in cities such as San Francisco or Boston, which have a lot of colleges and universities, don’t ask for the moon when an employer inquires about your salary expectations. An overly optimistic opening will make you look unreasonable and scare the employer away. WHEN THE OTHER SIDE WON’T BARGAIN The second exception concerns special markets in which there is, for one reason or another, no expectation of bargaining. A friend in the management consulting business pointed this out to me. When someone calls and asks him to do an engagement, he quotes a price and, nine times out of ten, either gets the job or does not. Haggling is not part of the normal engagement process. His asking price conveys a message to his customers about his reputation and sophistication. His prospective customer, meanwhile, is shopping for the right level of sophistication by assembling price quotes. My friend has learned to name a price that is high enough to carry a “premium services” message, but not so high that prospective clients think he is out of their league. Question 3: What Sort of Concession Strategy Works Best? Research confirms that people receiving concessions often feel better about the bargaining process than people who get a single firm, “fair” price. In fact, they feel better even when they end up payingmore than they otherwise might. One experiment compared three different concession strategies: (1) start high, then refuse to move, (2) start moderately, then refuse to move, and (3) start high, then gradually concede to the moderate point. The last of these strategies was the most successful by far. More agreements were concluded using this strategy. The parties employing the third strategy made more money per transaction than did those using the first two. And the people who faced negotiators using the third strategy reported much higher levels of satisfaction with their agreements than did people who faced those who refused to move. Concessions are the language of cooperation. They tell the other negotiator in concrete, believable terms that you accept the legitimacy of his or her demands and recognize the necessity of sacrifice on your own part to secure a joint decision. Concession Making in Different Situations TACIT COORDINATION (QUADRANT IV) The concession-making practice for Tacit Coordination situations need not detain us. Avoiding needless disputes and accommodating when conflict cannot be avoided is the best practice. If accommodation is not possible (the other side refuses to go first and you are stuck in a “mutual accommodation” impasse) don’t worry about concession tactics. Just try to solve the problem in a genuine, helpful way. Go first if you must. RELATIONSHIPS (QUADRANT II) When the relationship counts more than the issue in dispute, the best concession strategy is accommodation. The goal is to find out what the other party wants and give it to him or her with interest. Money is not the issue. If accommodation is impractical for some reason (the other party will not tell you what he or she wants), propose some simple and self-sacrificing compromise. Try to make the other party feel appreciated. FIGURE 9.1 The Situational Matrix: A Strategy Guide As simple as all this sounds, supercompetitive people have a “tin ear” for this advice. Because they treat most interactions as games and have trouble trusting others, they have no instinct for accommodation. They butt into line to get their seat on the airplane, and they haggle too hard when they should be more concerned with the relationship. Some useful advice for competitive people who find themselves in situations calling for diplomacy: Get help from someone with better people skills. For those of us stuck negotiating with competitive people who do not understand that in some situations the stakes don’t matter, keep your sense of humor, accommodate, and consider whether you want to continue dealing with a person who doesn’t understand the value of relationships. TRANSACTIONS (QUADRANT III) When the stakes are all that matter, research shows that a firm concession strategy works best. In simple, price-only negotiations (what scholars call “distributive bargaining” situations), classic haggling is the rule: Open optimistically, hold for a bit, show a willingness to bargain, then make a series of progressively smaller concessions as you close in on your expectation level. Cooperative people may not be very good at the haggling game, but they must nevertheless learn to play it in competitive situations. Note carefully: Hagglers’ concessions initially converge on their expectation levels—not their absolute bottom lines. Why? Because the declining size of hagglers’ concessions (in either percentage or absolute money terms) sends a powerful signal that they are getting close to a resistance point. They want you to think that their expectation level is their “bottom line.” This is a bluff. If you resist at their initial target level, hagglers will reluctantly continue making concessions toward their real bottom line—the point at which they would really rather walk away than do the deal. % In more important, high-stakes deals, you should also be careful not to make big concessions too early. Start slowly. Why? Because big moves made early in bargaining can confuse the other side. Let’s say you are in a negotiation with a big chain to sell your small video store business. You will have no future role in the venture—it is a straight buyout. You have several issues before you: the price, the “currency” (whether you will take the price in cash or the acquiring firm’s stock), and the closing date for the deal. The larger firm opens with an aggressive bid that covers all three issues: a low price, an all-stock deal, and a delayed closing date (which we’ll assume favors the buyer in this deal). What happens if, in your response, you move straight to your bottom line, hoping to conclude negotiations quickly and amicably? You propose a medium valuation (which is where you want to end up), accept the all-stock proposal, and ask for closing in two months (a reasonable time). You are surprised when the buyer’s next offer moves just inches off its low valuation and keeps the far-off closing. The buyer does not even mention your agreement to the all-stock aspect of its offer. You begin to feel angry. What is the problem here? When you make large concessions early in high-stakes transactional bargaining, you send a set of messages. One message is: I really want this deal. That message has leverage implications, and the other side may develop high expectations regarding the final price. It will want to test that hypothesis. If you suddenly dig in and refuse to move after being extremely flexible at the start, the other side may have trouble adjusting its expectations in light of the first impression you gave. You may even lose the deal. The second message you send is: The issues I conceded were not important to me. By agreeing completely to the all-stock idea right away, you signaled your satisfaction with that term. But guess what? The other party may give you zero credit for this concession because you gave it up so easily. You have now told them, in effect, “I did not want cash.” Consider the other side’s point of view. The acquiring firm may have been deeply worried that you would demand cash. It might have been willing to raise its price significantly or pay you some cash on the side for a consulting contract to induce you to use its stock as currency. But now you will get nothing for this concession. Negotiation teachers call this phenomenon “concession devaluation.” This is a fancy name for the truth contained in an old saying: “What we obtain too cheaply, we esteem too lightly.” Competitive opponents will naturally take advantage of everything you give them, but even accommodating people will alter their expectations in the light of your offhanded concession behavior. If you give up something without even a comment, the other side’s estimate of the value of your concession actually goes down because of your casual treatment of the issue. “I guess we valued this item incorrectly in our planning,” the other side’s negotiators say to themselves. “She didn’t really care about getting cash. If the issue isn’t worth anything to her, it isn’t worth anything to us, either.” Issue Trading Versus Haggling in Transactions: Integrative Bargaining % If the concession rule for haggling is “Start high and concede slowly,” the rule of thumb for integrative bargaining is to make big moves on your “little” (less important) issues and little moves on your “big” (most important) issues. But remember the danger of concession devaluation and never give up anything (even a “little” issue) without a demonstration that the concession is meaningful to you. % Parties often trade issues in clusters, using a formulation well known to negotiation experts: IF you give us what we want on issues A and B, THEN we might consider concessions on issues X and Y. The “if ... then” formula ensures that you never make a concession without linking it to a mutual concession from the other party. And of course, issues A and B are the most important ones to the party making the offer while issues X and Y tend to be lesser priorities. The parties may eventually need to haggle and fight over some of the issues that both think are important, but they have “issuetraded” on the ones that each can concede at relatively low cost. Making Concessions in Balanced Concerns Situations (QUADRANT I) % In a Balanced Concerns situation, where both the future relationship and the stakes are roughly equal in importance for both sides, a variety of different bargaining and problem-solving procedures work. The goal is to address as many priorities as possible, make sure that each side gets its “fair share” on such issues as price, and maintain good working relationships between the parties going forward. Because the stakes matter, you should still come to the table with high expectations. You will want to move slowly on your least important issues first and use the conditional “if... then” formulation for concession making. All trades should be reciprocal. Because the relationship matters to both sides, more imaginative kinds of bargaining tactics are both possible and desirable than is the case in Transactions. Aggressive, hardball moves and transparent gambits do not work well. They are too bruising to personal feelings and usually obscure the shared interests the parties bring to the table. Instead, each party needs to probe more deeply into the real needs underlying the other side’s demands and seek imaginative solutions. % Reseach suggests that genuine conflict between people over their legitimate goals, which many well-meaning people try to avoid or minimize in the name of harmonious human relations, actually helps energize the collaborative problem-solving process in a Balanced Concerns situation. A clash between two people with well-considered high expectations can motivate creative thinking as both sides strive to solve their problem, maintain their principles, keep their relationships in working order, and hit their targets. People with a problem-solving style have a talent for using conflict to keep the bargaining process going without letting the conflict degenerate into a personal battle. A Brief Note on the “Good Guy/Bad Guy” Routine There is one concession-making ploy that competitive negotiators use so often in high-stakes dealsthat it deserves a special mention. This is the “good guy/bad guy” routine. You know you are up against this when you find yourself liking one of the other side’s negotiators and wishing another one would jump off a cliff. Another sign: The other side’s representative tells you that your demands sound reasonable to her—but that someone else who isn’t there (the bad guy) would never agree. The good guy/bad guy gambit draws its effectiveness from a number of psychological phenomena we have met before. The good guy opens the negotiation with some friendly rapport-building chatter about shared interests and goals. The good guy appeals to our tendency to like people who agree with us and who are familiar and similar, as discussed in Chapters 4 and 8. The bad guy then takes over when it comes to the opening. He opens at an outrageous level or attacks our proposal, as the case may be. This aggressive, confrontational moment startles us, creating a vision of potential loss as we see the deal disappearing and begin thinking about the further compromises we may need to make. The bad guy wants to lower our expectations and anchor us at his end of the bargaining range so we will make our adjustments from there. Just about when we are ready to quit because the bad guy is not moving on anything, the good guy steps back in and insists that the bad guy make a concession. This makes the good guy an advocate for the norm of reciprocity and we like him even more. We start looking at the good guy as a champion of reasonableness and begin taking his advice about what needs to be done to bridge the gap between our side and the bad guy. In this way, the good guy/bad guy routine takes advantage of the contrast effect we discussed in connection with optimistic openings. The good guy—who might appear demanding if viewed alone— looks reasonable, if not saintly, when seen sitting next to Godzilla. You are more likely to make concessions to the good guy because he seems so much nicer and his demands look so comparatively attractive. The way to counter the good guy/bad guy routine is simple: Name the tactic publicly at the table and demand clarification on the issue of authority. Fight fire with fire. “It looks as if one of you is playing the good guy and the other is playing the bad guy,” you might say. “I had hoped we could use a more straightforward process to reach a fair deal. Before we proceed further, I would like to know who has authority to agree to what. I cannot negotiate with people who lack authority to close.” If the bad guy is a lawyer or other adviser, throw him or her out. Insist on trading directly with the decision maker. Let the “deal makers” take over from the “deal breakers.” Opening and 'Concession Making' Summary CHAPTER 10 - Step 4: Closing and Gaining Commitment Closing Factor 1: Injecting Urgency by Using the Scarcity Effect One of the most primal and powerful psychological levers in every negotiation is what psychologists call the scarcity effect. This label refers to our human tendency to want things more when we think the supply is running out. Your ability to get what you want in negotiation often depends on the other side’s perception that it has something to lose from a “no deal” result. You can and often should appeal to scarcity arguments from the very beginning of the information exchange stage. But it is usually at the closing stage that these arguments are tested most strenuously. As stated in the research, “Scarcity enhances the value of anything that can be possessed, is useful to its possessor, and is transferable from one person to another.” When we think something we want is or is about to become scarce, we push an imaginary panic button labeled “Act Now” to avoid feeling regret that we missed an opportunity. % SCARCITY CAUSED BY MANY PEOPLE WANTING THE SAME THING: COMPETITION % SCARCITY CAUSED BY TIME RUNNING OUT: DEADLINES % SCARCITY CAUSED BY WALKOUTS Perhaps the most dramatic method of inducing a scarcity effect is to give the other side a “take it or leave it” ultimatum and then, when the other party protests, get up from the table and walk away. Nothing quite matches the emotional punch of watching a deal you want literally walk out the door. All walkouts look spontaneous, but many are pure theater. If the other side is relatively naive and eager to do the deal, an experienced, competitive negotiator can use a walkout to play on its fears, dramatizing the need for quick capitulation. Walkouts also underline the importance of especially important issues. Closing Factor 2: Overcommitment to the Bargaining Process Before we press on to see what finally happened to Kravis in the RJR case, let’s look at a second psychological phenomenon that came into play that day in 1988. Psychologists call it overcommitment. Overcommitment derives from our human desire to avoid admitting failure or accepting loss when we have invested heavily in a prior course of action or decision. The more time someone invests in an initially sensible activity, the more committed he or she becomes to seeing it through, even though the decision may no longer make sense. Let’s begin with a simple, nonnegotiation illustration of overcommitment. Imagine you are at an amusement park and hear about a popular “splash and crash” ride. When you arrive at the ride there is a line, but you decide to give it a try. You have stood there two or three minutes, not moving much, when a park employee announces that the waiting time will be an hour and a half. Do you stay in line or go do something else? Now imagine the same situation, but this time the employee announces the news after you have stood in line for forty-five minutes. The employee tells you that the line will take an hour and half to clear for people just entering it and for you it will take an additional forty-five minutes. Do you stay in line for the extra forty-five minutes or drop out and do something else? Research on overcommitment suggests you are more likely to quit the line in case 1 than in case 2, even though the total waiting time is identical. Why? Because in case 2, you have invested a full forty-five minutes that you will “lose” by dropping out of line. In case 1, you “lose” only a few minutes. Once you have made an initial, significant investment in waiting, you are inclined to invest more time to achieve a realizable goal. Leveraging Loss Aversion Psychologists, casino owners, and Wall Street stockbrokers have all profited for years from this well-documented human quirk of loss aversion. People who play slot machines often feel an urge to“get back to even” once they start to lose money. They keep pouring in tokens, throwing good money after bad. Inexperienced investors are reluctant to sell their losing stocks, hoping that these unlucky investments will turn around and bounce back to the break-even point. So they sell their winners and hold their losers, exactly the opposite of what many professional portfolio managers do. How does this self-defeating psychological quirk apply to negotiation? As we invest increasingly significant amounts of time, energy, and other resources in the actual negotiation process, we become more and more committed to closing just the way the person in the amusement park line becomes increasingly determined to get to the ride as more and more time passes. The overcommitment phenomenon can occur spontaneously even when the other side is acting in good faith. But manipulative opponents can string negotiations out solely for the purpose of getting us overcommitted. They spring their trap just before the closing by apologetically introducing a lastminute demand that is “essential” to the agreement. “We’ve come so far,” they plead. “Don’t let all this time and effort be wasted.” Rather than face the loss of an unsuccessful negotiation, we may be more inclined to give them at least some of what they want and save the deal. Overcommitment, in combination with the contrast effect discussed in Chapter 9, explains another common closing tactic used by slick negotiators that is called the nibble. The “nibbler” modestly requests small favors just before a deal closes. In the context of a lengthy and complicated negotiation, most people do not want to spoil either the deal or the relationship by quibbling over such small items. They often make the requested concessions. By nibbling at all their contracts, however, professional negotiators can add as much as 3 to 5 percent in additional value to their deals over a year’s time. The antidote to overcommitment and nibbling is obvious. If you know you are negotiating with a nibbler, hold something back to give away at the end. If the other party is less familiar to you, keep your eye on your goals, make sure the other party is just as invested in the negotiation process as you are, and do not respond sympathetically to last-minute demands. We would be outraged if someone tried to charge us extra money to get on the amusement park ride after we had patiently waited for an hour with our ticket in hand. You should have the same attitude about last-minute requests in negotiation. At the very least you should insist on a reciprocal concession. Softer Closing Tactics: Shall We Split the Difference? Why is splitting the difference so popular? First, it appeals to our sense of fairness and reciprocity, thus setting a good precedent for future dealings between the parties. A split is very much like the fifty-fifty sharing of money in the ultimatum game discussed in Chapter 4. Each side makes an equal concession simultaneously. What could be fairer than that? Second, it is simple and easy to understand. It requires no elaborate justification or explanation. The other side sees exactly what you are doing. Third, it is quick. For people who do not like to negotiate or are in a hurry, splitting the difference offers a way out of the potentially messy interpersonal conflict that looms whenever a negotiation occurs. Splitting the difference is such a common closing tactic that it often seems rude and unreasonable to refuse, regardless of the situation. This is taking a good thing too far, however. There are at least twoimportant situations in which I would hesitate to split the difference. First, you should be careful that the midpoint being suggested is genuinely fair to your side. If you have opened at a reasonable price and the other party opened at an aggressive one, the midpoint is likely to favor the other party by a big margin. So don’t split the difference at the end if there was a lack of balance at the beginning. Second, when a lot of money or an important principle is on the line and relationships matter, quickly resorting to splitting may leave opportunities for additional, creative options on the table. ditto for the apprentices. Both would have been unhappy half the time. Instead of this “nobody wins” outcome, choose to not to deal. No deal is better than a bad deal. What Happens if Negotiations Break Down? Jump-starting the Negotiation Process Perhaps the easiest way to overcome impasse is to leave yourself a back door through which to return to the table when you get up to leave it. “In light of the position you have taken,” you might say as you pack your bags, “we are unable to continue negotiations at this time.” An attentive opponent will pick up on your use of the words “at this time” and tactfully ask you later if the time has come to reinitiate talks. This back door also allows you to contact the other side at a later date without losing face. If the other negotiator leaves in a genuine fit of anger, he may not be very careful about leaving a back door open. If so, you should consider how you can let him back in without unnecessary loss of face. You must, in one expert’s phrase, build him a “golden bridge” across which to return to the table. Such bridges include “forgetting” that he made his ultimatum in the first place or recalling his last statement in a way that gives him an excuse for returning. When miscommunication is the problem, a simple apology may be enough to get the parties back on track. If the relationship has deteriorated beyond apologies, changing negotiators or getting rid of intermediaries altogether may be necessary. Don’t Be Satisfied with an Agreement—Get a Commitment The goal of all negotiations is to secure commitment, not merely agreement. Four Degrees of Commitment 1. In virtually every negotiation, the commitment process begins with a simple social ritual. 2. As the promise being made increases in gravity, the social rituals supporting it also increase in complexity. Many of these more complex rituals include some form of public announcement or disclosure. 3. Accountability also enhances commitment. If the promisor’s personal reputation is at risk when his or her performance falls short, he or she is more likely to perform as promised. 4. In some transactions, no device, legal or otherwise, is solid enough to fully secure a commitment. In these cases, it is often both prudent and efficient to use a simultaneous exchange to close the deal. 'Bargaining and Closing' Summary CHAPTER 11 - Bargaining with the Devil Without Losing Your Soul: Ethics in Negotiation The Core Ethical Problem for Negotiators Professor James J. White, a negotiation teacher at the University of Michigan Law School, describes the problem this way: “The negotiator’s role is at least passively to mislead his opponent about his settling point while at the same time to engage in ethical behavior.” White’s statement embodies the contradictions many people encounter when they start thinking about bargaining ethics. Is it really possible to speak coherently about ethical ways of misleading someone for a selfish purpose? What does White mean by “passive” deception? Might not active deception about a little issue such as about a catalog price be more ethical than passive deception about something really important in a multibillion-dollar deal? There are no easy answers to these questions. And the problems become even tougher when you add professional ethical duties such as those imposed on lawyers, physicians, accountants, and others into the mix. The Minimum Standard: Obey the Law There are six major elements of a fraud case. A bargaining move is fraudulent when a speaker makes a (1) knowing (2) misrepresentation of a (3) material (4) fact (5) on which the victim reasonably relies (6) causing damages. ELEMENT 1: “KNOWING” To commit fraud, a negotiator must have a particular state of mind with respect to the fact he or she misrepresents. The misstatement must be made “knowingly.” One way of getting around fraud, therefore, might be for the speaker to avoid direct contact with information that would lead to a “knowing” state of mind. ELEMENT 2: “MISREPRESENTATION” In general, the law requires a negotiator to make a positive misstatement before a statement is judged fraudulent. A basic legal rule for commercial negotiators is “Be silent and be safe.” As a practical matter, of course, silence is difficult to maintain if one’s bargaining opponent is an astute questioner. In the face of inconvenient questions, negotiators are often forced to resort to verbal feints and dodges such as “I don’t know about that” or, when pressed, “That is not a subject I am at liberty to discuss.” When you choose to lie in response to a pointed question probing the strength of your bargaining position, you immediately raise the risk of legal liability. As we shall see below, however, some lies are not “material” and the other party may be charged with a duty to discount the truth of what you tell them. Surprisingly, there are circumstances when it may be fraudulent to keep your peace about an issue even if the other side does not ask about it. When does a negotiator have a duty to voluntarily disclose matters that may hurt his bargaining position? American law imposes affirmative disclosure duties in the following four circumstances: 1. When the negotiator makes a partial disclosure that is or becomes misleading in light of all the facts. If you say your company is profitable, you may be under a duty to disclose whether you used questionable accounting techniques to arrive at that statement. You should also update your prior statement if you show a loss in the next quarter and negotiations are still ongoing. 2. When the parties stand in a fiduciary relationship to each other. In negotiations between trustees and beneficiaries, partners in a partnership, shareholders in a small corporation, or members of a family business, parties may have a duty of complete candor and cannot rely on the “be silent and be safe” approach. 3. When the nondisclosing party has vital information about the transaction not accessible to the other side. In general, sellers have a greater duty to disclose hidden defects about their property than buyers do to disclose “hidden treasure” that may be buried there. A home seller must disclose termite infestation in her home, but an oil company need not voluntarily disclose that there is oil on a farmer’s land when negotiating to purchase it. This is a slippery exception; the best test is one of conscience and fairness. 4. When special codified disclosure duties, such as those regarding contracts of insurance or public offerings of securities, apply. Legislatures sometimes impose special disclosure duties for particular kinds of transactions. In the United States, for example, many states now require home sellers to disclose all known problems with their houses. If none of these four exceptions applies, neither side is likely to be found liable for fraud based on a nondisclosure. Each party can remain silent, passively letting the other proceed under its own assumptions. ELEMENT 3: “MATERIAL” Suppose that an art gallery owner has been given authority by an artist to sell one of the artist’s paintings for any price greater than $10,000. Is it fraud for the gallery owner, as part of a negotiation with a collector, to say, “I can’t take less than $12,000”? In fact, she does have authority to sell the painting for anything above $10,000, so there has been a knowing misrepresentation of fact. Suppose the buyer says, “My budget for this purchase is $9,000,” when she is really willing to spend $11,000? Same thing. The legal question in both cases is whether these facts are “material.” They are not. In fact, lies about demands and bottom-line prices are so prevalent in bargaining that many professional negotiators do not consider such misstatements to be lies, preferring the term “bluffs.” Why? Such statements allow the parties to assert the legitimacy of their preferences and set the boundaries of the bargaining range without incurring a risk of loss. Misleading statements about bottom-line prices and demands also enable parties to test the limits of the other side’s commitment to their expressed preferences. ELEMENT 4: “FACT” On the surface, it appears that only misstatements of objective facts are occasions for legal sanctions. Businessmen seeking to walk close to the legal line are therefore careful to couch their sales talk in negotiation as opinions, predictions, and statements of intention, not statements of fact. Moreover, a good deal of exaggeration or puffing about product attributes and likely performance is viewed as a normal aspect of the selling process. Buyers and sellers cannot take everything said to them at face value. The surface of the law can be misleading, however. Courts have found occasion to punish statements of intention and opinion as fraudulent when faced with particularly egregious cases. The touchstone of the law of fraud is not whether the statement at issue was one of pure fact but rather whether the statement succeeded in concealing a set of facts the negotiator preferred to keep out of sight. Suppose you are borrowing money from your uncle and tell him that you plan to spend the loan on college tuition. In fact, you are really going to buy a fancy, new sports car. Fraud? Possibly. In the memorable words of a famous English judge, “The state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion.” Lies regarding intention even have a special name in the law: promissory fraud. The key element in a promissory fraud case is proof that the speaker knew he could not live up to his promise at the time the promise was made. In other words, he made the promise with his fingers crossed behind his back. If you are the victim, you must also show that the other side’s intention going into the deal went to its very heart—that is, that the statement of intention was “material.” What about statements of opinion? Self-serving statements about the value of your goods or the qualifications of your product or company are the standard (legal) fare of the negotiating table. However, when negotiators offer statements of opinion that are flatly contradicted by facts known to them about the subject of the transaction, they may be liable for fraud. In one New York case, for example, the seller of a machine shop business opined to a prospective buyer that the buyer would have “no trouble” securing work from his largest customer. In fact, the seller was in debt to his customer, intended to pay off this debt from the proceeds of the sale to the buyer, and had virtually no work there due to his reputation for poor workmanship. The buyer successfully proved that the sale had been induced by the seller’s fraudulent statement of opinion and collected damages. What seems to matter in these cases is unfairness. If a statement of intention or opinion so conceals the true nature of the negotiation proposal that a bargaining opponent cannot accurately assess an appropriate range of values or risks on which to base the price, then it may be fraudulent. ELEMENT 5: “RELIANCE” Negotiators who lie sometimes defend themselves by saying, in effect, “Only a fool could have believed what I said. The other party had no business relying on me to tell him the truth—he should have investigated for himself.” As we saw in our discussion of lies about other offers, this defense works pretty well when both sides are on roughly the same footing. But when one side has a decided advantage, as does a professional buyer or seller against a consumer or small business, American courts are more sympathetic to the idea that the victim reasonably relied on the lie. In addition, courts are sympathetic to those who, in good faith, rely on others to treat them fairly in the negotiation process and who have that trust violated by more powerful firms trying to steal their trade secrets and other information. There have been a number of cases, for example, allowing recoveries to independent inventors and others who disclosed trade secrets in the course of negotiations to sell their discoveries. The prospective buyers in these cases are typically big companies that attempted to use the negotiation process as a way of getting something for nothing. The prudent negotiator, however, always secures an express confidentiality agreement if secret information or business plans must be disclosed in the course of the information exchange process. One trick that manipulative negotiators use to avoid liability after they have misstated important facts or improperly motivated a transaction is to write the true terms and conditions into the final written agreement. If the victim signs off on the deal without reading this contract, he will have a hard time claiming reasonable reliance on the earlier misstatements in a fraud case later on. For example, suppose you negotiate the sale of your company’s principal asset, an electronic medical device, to a big medical products firm. During the negotiations, the company assures you that it will aggressively market the device so you can earn royalties. The contract, however, specifically assigns it the legal right to shelve the product if it wishes. After the sale, it decides to stop marketing your product and you later learn the company never really intended to sell it; it was just trying to get your product off the market because it competed with several of its own. In a case like this, a court held that the plaintiffs were stuck with the terms of the final written contract. The lesson here is clear: Read contracts carefully before you sign them, and question assurances that contract language changing the nature of the deal is just a technicality or was required by the lawyers. ELEMENT 6: “CAUSATION AND DAMAGES” You cannot make a legal claim for fraud if you have no damages caused by the fraudulent statement or omission. People sometimes get confused about this. The other negotiator lies in some outrageous and unethical way, so they assume the liar’s conduct is illegal. It may be, but only if that conduct leads directly to some quantifiable economic loss for the victim of the fraud. If there is no such loss, the right move is to walk away from the deal (if you can), not sue. Three Schools of Bargaining Ethics The three schools of bargaining ethics I want to introduce for your consideration are (1) the “It’s a game” Poker School, (2) the “Do the right thing even if it hurts” Idealist School, and (3) the “What goes around, comes around” Pragmatist School. Let’s look at each one in turn. As I describe these schools, try to decide which aspects of them best reflect your own attitudes. After you figure out where you stand today, take a moment and see if that is where you ought to be. My advice is to aim as high as you can, consistent with your genuinely held beliefs about bargaining. In the pressured world of practice, people tend to slide down rather than climb up when it comes to ethical standards. THE “IT’S A GAME” POKER SCHOOL The Poker School of ethics sees negotiation as a “game” with certain “rules.” The rules are defined by the law, such as the legal materials we covered above. Conduct within the rules is ethical. Conduct outside the rules is unethical. The modern founder of the Poker School was Albert Z. Carr, a former Special Consultant to President Harry Truman. Carr wrote a book in the 1960s called, appropriately enough, Business as a Game. In a related article that appeared in the Harvard Business Review, Carr argued that bluffing and other misleading but lawful negotiating tactics are “an integral part of the [bargaining] game, and the executive who does not master [these] techniques is not likely to accumulate much money or power.” People who adhere to the Poker School readily admit that bargaining and poker are not exactly the same. But they point out that deception is essential to effective play in both arenas. Moreover, skilled players in both poker and bargaining exhibit a robust and realistic distrust of the other fellow. Carr argues that good players should ignore the “claims of friendship” and engage in “cunning deception and concealment” in fair, hard bargaining encounters. When the game is over, members of the Poker School do not think less of a fellow player just because that person successfully deceived them. In fact, assuming the tactic was legal, they may admire the deceiver and vow to be better prepared (and less trusting) next time. We know how to play poker, but how exactly does one play the bargaining “game”? Stripped to its core, it looks like this: Someone opens, and then people take turns proposing terms to each other. Arguments supporting your preferred terms are allowed. You can play or pass in each round. The goal is to get the other side to agree to terms that are as close as possible to your last proposal. In the bargaining game, it is understood that both sides might be bluffing. Bluffs disguise a weak bargaining hand, that is, the limited or unattractive alternatives you have away from the table, your inability to affect the other side’s alternatives, and the arguments you have to support your demands. Unlike poker players, negotiators always attempt to disclose a good hand if they have one in the bargaining game. So the most effective bluffs are realistic, attractive, difficult-to-check (but false) alternatives or authoritative (but false) supporting standards. Experienced players know this, so one of the key skills in the bargaining game is judging when the other party’s alternatives or arguments are really as good as he or she says. If the other side calls you on your bargaining bluff by walking away or giving you a credible ultimatum, you lose. Either there will be no deal when there should have been one, or the final price will be nearer to their last offer than to yours. As mentioned above, the Poker School believes in the rule of law. In poker, you are not allowed to hide cards, collude with other players, or renege on your bets. But you are expected to deceive others about your hand. The best plays come when you win the pot with a weak hand or fool the other players into betting heavily when your hand is strong. In bargaining, you must not commit outright, actionable fraud, but negotiators must be on guard for anything short of fraud. The Poker School has three main problems as I see it. First, the Poker School presumes that everyone treats bargaining as a game. Unfortunately, it is an empirical fact that people disagree on this. For a start, neither the idealists nor the pragmatists (more on these below) think bargaining is agame. This problem does not deter the Poker School, which holds that the rules permit its members to play even when the other party disagrees about this premise. Second, everyone is supposed to know the rules cold. But this is impossible, given that legal rules are applied differently in different industries and regions of the world. Finally, as you now know (having read about the legal treatment of fraud), the law is far from certain even within a single jurisdiction. So you often need a sharp lawyer to help you decide what to do. THE “DO THE RIGHT THING EVEN IF IT HURTS” IDEALIST SCHOOL The Idealist School says that bargaining is an aspect of social life, not a special activity with its own unique set of rules. The same ethics that apply in the home should carry over directly into the realm of negotiation. If it is wrong to lie or mislead in normal social encounters, it is wrong to do so in negotiations. If it is OK to lie in special situations (such as to protect another person’s feelings), it is also OK to lie in negotiations when those special conditions apply. Idealists do not entirely rule out deception in negotiation. For example, if the other party assumes you have a lot of leverage and never asks you directly about the situation as you see it, you do not necessarily have to volunteer information weakening your position. And the idealist can decline to answer questions. But such exceptions are uncomfortable moments. Members of the Idealist School prefer to be candid and honest at the bargaining table even if it means giving up a certain amount of strategic advantage. The Idealist School draws its strength from philosophy and religion. For example, Immanuel Kant said that we should all follow the ethical rules that we would wish others to follow. Kant argued that if everyone lied all the time, social life would be chaos. Hence, you should not lie. Kant also disapproved of treating other people merely as the means to achieve your own personal ends. Lies in negotiation are selfish acts designed to achieve personal gain. This form of conduct is therefore unethical. Period. Many religions also teach adherents not to lie for personal advantage. Idealists admit that deception in negotiation rarely arouses moral indignation unless the lies breach a trust between friends, violate a fiduciary responsibility, or exploit people such as the sick or elderly, who lack the ability to protect themselves. And if the only way you can prevent some terrible harm like a murder is by lying, go ahead and lie. But the lack of moral outrage and the fact that sometimes lying can be defended does not make deception in negotiations right. Idealists strongly reject the idea that negotiations should be viewed as “games.” Negotiations, they feel, are serious, consequential communication acts. People negotiate to resolve their differences so social life will work for the benefit of all. People must be held responsible for all their actions, including the way they negotiate, under universal standards. Idealists think that the members of the Poker School are predatory and selfish. For its part, the Poker School thinks that idealists are naive and even a little silly. When members of the two schools meet at the bargaining table, tempers can flare. Some members of the Idealist School have recently been trying to find a philosophical justification for bluffs about bottom lines. There is no agreement yet on whether these efforts have succeeded in ethical terms. But it is clear that outright lies such as fictitious other offers and better prices are unethical practices under idealist principles. The big problem for the idealists is obvious: Their standards sometimes make it difficult toproceed in a realistic way at the bargaining table. Also, unless adherence to the Idealist School is coupled with a healthy skepticism about the way other people will negotiate, idealism leaves its members open to exploitation by people with standards other than their own. These limitations are especially troublesome when idealists must represent others’ interests at the bargaining table. Despite its limitations, I like the Idealist School. Perhaps because I am an academic, I genuinely believe that the different parts of my life are, in fact, a whole. I aspire to ethical standards that I can apply consistently. I will admit that I sometimes fall short of idealism’s strict code, but by aiming high I hope I am leaving myself somewhere to fall that maintains my basic sense of personal integrity. I confess my preference for the Idealist School so you will know where I am coming from in this discussion. But I realize that your experience and work environment may preclude idealism as an ethical option. That’s OK. As I hope I am making clear, idealism is not the only way to think about negotiation in ethical terms. THE “WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND” PRAGMATIST SCHOOL The final school of bargaining ethics, the Pragmatist School, includes some original elements as well as some attributes of the previous two. In common with the Poker School, this approach views deception as a necessary part of the negotiation process. Unlike the Poker School, however, it prefers not to use misleading statements and overt lies if there is a serviceable, practical alternative. Uniquely, the Pragmatist School displays concern for the potential negative effects of deceptive conduct on present and future relationships. Thus, lying and other questionable tactics are bad not so much because they are “wrong” as because they cost the user more in the long run than they gain in the short run. As my last comment suggests, people adhere to this school more for prudential than idealistic reasons. Lies and misleading conduct can cause serious injury to one’s credibility. And credibility is an important asset for effective negotiators both to preserve working relationships and to protect one’s reputation in a market or community. This latter concern is summed up in what I would call the pragmatist’s credo: What goes around comes around. The Poker School is less mindful of reputation and more focused on winning each bargaining encounter within the rules of the “game.” What separates the Pragmatist School from the Idealist School? To put it bluntly, a pragmatist will lie a bit more often than will an idealist. For example, pragmatists sometimes draw fine distinctions between lies about hard-core facts of a transaction, which are always imprudent (and often illegal), and misleading statements about such things as the rationales used to justify a position. A pragmatic car salesman considers it highly unethical to lie about anything large or small relating to the mechanical condition of a used car he is selling. But this same salesman might not have a problem saying “My manager won’t let me sell this car for less than $10,000” even though he knows the manager would sell the car for $9500. False justification and rationales are marginally acceptable because they are usually less important to the transaction and much harder to detect as falsehoods than are core facts about the object being bought and sold. Pragmatists are also somewhat looser within the truth when using so-called blocking techniques— tactics to avoid answering questions that threaten to expose a weak bargaining position. For example, can you ethically answer “I don’t know” when asked about something you do know that hurts your position? An idealist would refuse to answer the question or try to change the subject, not lie by saying “I don’t know.” A pragmatist would go ahead and say “I don’t know” if his actual state ofknowledge is hard to trace and the lie poses little risk to his relationships. What would the pragmatists make of Sifford’s lie about his catalog price? My guess is that they would not consider this move an ethical problem. There were no relationship risks involved in Sifford’s fib. There was no question of constructing a good working relationship, no reputational interests at stake, and the salesman seemed to know exactly what Sifford was up to. He did not violate the salesman’s trust. An idealist, by contrast, would object to Sifford’s tactic on ethical grounds because it involved a lie designed to gain selfish advantage. Case closed. The Ethical Schools in Action As a test of ethical thinking, let’s take a simple example. Assume you are negotiating to sell a commercial building and the other party asks you whether you have another offer. In fact, you do not have any such offers. What would the three schools recommend you do? A Poker School adherent might suggest a lie. Both parties are sophisticated businesspeople in this deal, so a lie about alternatives is probably legally “immaterial.” But a member of the Poker School would want to know the answers to two questions before making his move. First, could the lie be easily found out? If so, it would be a bad play because it wouldn’t work and might put the other side on guard with respect to other lies he might want to tell. Second, is a lie about alternatives the best way to leverage the buyer into making a bid? Perhaps a lie about something else —a deadline, for example—might be a better choice. Assuming the lie is undetectable and will work, how might the conversation sound? Buyer: Do you have another offer? Poker School Seller: Yes. A Saudi Arabian firm presented us with an offer for $______ this morning, and we have only forty-eight hours to get back to it with an answer. Confidentiality forbids us from showing you the Saudi offer, but rest assured that it is real. What would you like to do? How would an idealist handle this situation? There are several idealist responses, but none would involve a lie. One response would be the following. Buyer: Do you have another offer? Idealist Seller 1: An interesting question—and one I refuse to answer. Of course, that refusal speaks volumes to the buyer. Another approach would be to adopt a policy on “other buyer” questions. Buyer: Do you have another offer? Idealist Seller 2: An interesting question, and one I receive quite often. Let me answer you this way. The property’s value to you is something for you to decide based on your needs and your own sense of the market. However, I treat all offers with the greatest confidence. I will not discuss an offer you make to me with another buyer, and I would not discuss any offer I received from someone else with you. Will you be bidding? Of course, this will work for an idealist only if he or she really and truly has such a policy—a costly one when there is another attractive offer he or she would like to reveal.A final idealist approach would be to offer an honest, straightforward answer. An idealist cannot lie or deliberately mislead, but he is allowed to put the best face he can on the situation that is consistent with the plain truth. Buyer: Do you have another offer? Idealist Seller 3: To be honest, we have no offers at this time. However, we are hopeful that we will receive other offers soon. It might be in your interest to bid now and take the property before competition drives the price up. How about the pragmatists? They would suggest using somewhat more sophisticated, perhaps even deceptive, blocking techniques. These techniques would protect their leverage in ways that were consistent with maintaining working relationships. Once again, assume that the buyer has asked the “other offer” question and there are no other offers. Here are five ways a pragmatist might suggest you block this question to avoid an out-and-out factual lie about other offers while minimizing the damage to your leverage. Some of these blocking techniques would work for idealists, too. • Declare the question out of bounds. (“Company policy forbids any discussion of other offers in situations like this”—note that, if untrue, this is a lie, but it is one that carries less risk to your reputation because it is hard to confirm. If there really is such a company policy, an idealist could also use this move to block the question.) • Answer a different question. (“We will not be keeping the property on the market much longer because the market is moving and our plans are changing.” Again, if untrue, this statement is a mere lie about a “rationale” that troubles pragmatists less than idealists.) • Dodge the question. (“The more important question is whether we are going to get an offer from you—and when.”) • Ask a question of your own. (“What alternatives are you examining at this time?”) • Change the subject. (“We are late for our next meeting already. Are you bidding today or not?”) Blocking techniques of this sort serve a utilitarian purpose. They preserve some leverage (though not as much as the Poker School) while reducing the risk of acquiring a reputation for deception. Relationships and reputations matter. If there is even a remote chance of a lie coming back to haunt you in a future negotiation with either the person you lie to or someone he may interact with, the pragmatists argue that you should not do it. So—which school do you belong to? Or do you belong to a school of your own such as “pragmatic idealism”? To repeat: My advice is to aim high. The pressure of real bargaining often makes ethical compromisers of us all. When you fall below the standard of the Poker School, you are at serious risk of legal and even criminal liability. Bargaining with the Devil: The Art of Self-defense Regardless of which school of bargaining ethics you adopt, you are going to face unscrupulous tactics from others on occasion. Even members of the Poker School sometimes face off against crooks. Are there any reliable means of self-defense to protect yourself and minimize the dangers? This section will give you some pointers on how to engage in effective self-defense against unethicaltactics at the bargaining table. First, let me relate a couple of stories of questionable bargaining behavior to see what the potential victims did to avert disaster. Then we will see how they could have perhaps done better. After that, I will list and describe some of the more common unethical gambits so you can recognize them when someone uses one against you. “That Was Just My Personal Price” The first story involves a used-car purchase. A St. Louis newspaper reporter named Dale Singer went out to buy his daughter a used car. After some shopping, he found a perfectly suitable vehicle on the used-car lot of a luxury-car dealership. The sticker price: $9,995. Singer haggled with the salesman, and the price quickly dropped to $9,000. Singer haggled a little more, and the salesman excused himself to visit with the sales manager. The salesman returned after a few minutes with a question. “Would you buy it today for $8,500?” the salesman asked. Singer liked the sound of that, but he was still shopping. He said he would get back to the salesman after he had looked around a bit more. A full day of car shopping turned up nothing more attractive than the first car. That evening Singer called the salesman back and offered $8,300. “I figured he probably wouldn’t budge from his $8,500 offer, but I knew that this was how the game was played,” he later explained. The salesman coolly replied that the price was now $8,900. When Singer protested, the salesman explained that the $8,500 figure had been his “personal offer” but that price had not been approved by the sales manager. Singer reminded him that the $8,500 figure had been mentioned just after a visit to the manager, and the salesman was sympathetic. He could sell the car for $8,700, but that was the best he could do. Outraged, Singer demanded to speak with the sales manager himself. The sales manager came on the line and explained that $8,500 was his cost, so $8,700 was his final price. Singer asked for the name of the general manager of the dealership, received it, and hung up. A few minutes later the telephone rang again. It was the sales manager. Because there had been a genuine misunderstanding over the price, he said, Singer could have the car for $8,500. Singer bought the car, but the dealership later balked at giving him full warranty service on the vehicle because of the low price he had paid. Singer ended up with a fully functioning car at the price he wanted to pay, but he was left wondering “Why should a customer have to work so hard to be treated fairly?” He felt abused and bitter. Singer did not know it, but the dealer “lowballed” him, tricking him into becoming committed to the car at a bargain price, then nudging the price up to exploit Singer’s rising interest in the vehicle. Lowballing is a classic, proven manipulative sales technique based on a hidden psychological premise. Singer was alert enough to reject it, but it works against many customers. The Bidding WarMy second story comes from a boom year in the New York City residential real estate market: 1997. A three-bedroom co-op apartment on Park Avenue went on the market, priced to sell at $1.7 million. Bonnie Chajet of Ashforth Warburg Associates had the exclusive listing. As Ms. Chajet tells the story, the listing had not been on long when a man showed up with his own broker, looked at the apartment, and placed an all-cash bid for $1.4 million. The seller rejected the bid, telling the buyer he wasn’t even close. Nothing more was heard from him. Four days passed with no interest being shown in the unit. Finally, a second potential buyer looked the apartment over in the company of a different broker. He placed a bid of $1.3 million, which the seller also rejected. Chajet was at least pleased that so many different brokers were picking up on the listing. Finally, after another three days with no takers, a third buyer with yet another broker appeared and bid $1.275 million. The seller rejected the third bid, too, but he began to wonder if Chajet had priced the apartment correctly. When her client questioned the list price, Chajet did some investigating. It soon turned out that the second and third bidders were friends of the first one. “They were all in it together,” explained Chajet, “trying to give the seller the signal that he’d better take the ‘high’ offer.” The apartment sold a few days later—for the full price. Chajet and her client were the victims of bid rigging, a blatant form of deception. Like lowballing, phony bids are designed to exert subtle psychological pressure on people who do not suspect they are being conned. Techniques for Coping with Unethical Tactics What do these two stories tell us about “bargaining with the devil”? Let’s see if we can make a list of effective self-defense moves. WATCH OUT FOR “TRANSACTIONS” Certain situations pose a higher risk of unethical conduct than others. It is no coincidence that these two stories (as well as Darrell Sifford’s) were Transaction events (see Chapter 7). When the price is the primary issue and there are limited prospects for future dealings between the parties, there is a higher risk of ethical problems. One might have hoped that the car dealership in Singer’s story would have seen the sale as part of a potential relationship rather than simply a transaction, but the used-car segment of even a luxury-car business is sometimes staffed with people paid on commission who couldn’t care less about customer relations. Be on guard whenever the stakes matter and the relationship does not. The risk of unethical conduct rises even higher when competition is “hot.” Research shows that leverage imbalances at the bargaining table encourage unethical behavior. Interestingly, both the stronger and the weaker parties have incentives to lie and cheat. One set of authors concluded after their experiment that “it is to the advantage of those who possess little power to use deceit against those of greater power when they do not wish to comply with the latter’s demands.” Another set of scholars found that the more powerful party in an unbalanced situation can become “intoxicated” withhis leverage. They offer the opinion that “in general, negotiators with more power are more likely to abuse that power by using less ethical tactics.” RELY ON RELATIONSHIPS WHENEVER POSSIBLE When seeking bargaining partners, use your relationship network (see Chapter 4) to advantage. Try to get recommendations, referrals, and introductions that will show the other side that the relationship with you matters. This move somewhat mitigates the incentives to behave unethically that would otherwise apply. Singer might have saved himself some grief by shopping for a dealership rather than a car. He could have checked with friends and gotten the names of dealers with a high reputation for service and fair dealing. He could have approached the dealership with these referrals from known, valued customers as partial protection from exploitative conduct. Relationships could not have helped Chajet because in the real estate market one has to take all comers. But it is worth noting that the seller was saved in this deal by his professional relationship with his broker, Chajet herself. Without a broker, the seller might well have fallen for this con game. Research shows that, in general, the prospect of an ongoing relationship raises people’s ethical standards. As one scholar has put it, “When a negotiator does not anticipate having to ‘live with’ the consequences of using ethically marginal tactics, she is far more willing to use them.” PROBE, PROBE, PROBE Be alert to the potential for deception in negotiation. Most people tend to give others the benefit of the doubt when judging whether lies have been told. This bias is fine for most of our social interchanges and for Relationship and Tacit Coordination situations involving negotiation. But it can be costly when the stakes matter in bargaining. If your suspicions are aroused, as they were in both Singer’s and Chajet’s cases, don’t rest until you discover what is going on. Chajet saved her client by conducting an investigation into the fake bids, probably by checking with her network, that is, the brokers who had innocently accompanied the phony buyers. As an astute negotiator, Sir Frances Bacon, put it in an essay called “Of Negotiating” he wrote in 1597, “In dealing with cunning people, we must ever consider their needs to interpret their speeches.” Singer could have done much better on this score. The car salesman misled him about the price, but Singer was a victim as much of his own assumptions as of the salesman’s guile. The salesman spoke clearly and carefully: “Would you buy it today for $8,500?” Singer might have fleshed out this curiously phrased question before drawing his conclusion that the car was available at that price. “Are you making me a concrete offer at that price?” he could have asked. Probing will help you gain insight into whether the other side’s story holds together, but do not expect the other party to come right out and admit he is acting unethically. You will have to rely on your judgment as well as his conduct. Research suggests that it is very difficult to detect when others are lying and, even when you do, to discern what they are lying about. You should check as many sources of information as possible before you draw a firm conclusion. If you discover that the other side is acting unethically, should you call him or her on it? Perhaps— if that advances your goals. But I would wait to see if direct embarrassment is really necessary. Forexample, suppose the buyer in Chajet’s case turned out to be the only interested party. His check for $1.4 million is good and the offer is all cash. Should you take his money or confront him with his unethical conduct? I think I would take the cash. But I would wait until the check cleared before I gave him the deed. BE ASSERTIVE AND PERSISTENT When other people are acting unethically, it is up to you to insist on fairness. Singer ultimately got his price by pushing back, persevering, and refusing to be lowballed. Chajet’s seller also pushed back. He was not stampeded into a sale based on the sequence of declining bids. MAINTAIN YOUR OWN STANDARDS—DON’T SINK TO THEIRS It is tempting to engage in tit for tat when the other side uses unethical tactics. We get angry. We lose perspective and start down the unethical path ourselves. Avoid this trap. First, no matter what school of bargaining ethics you adhere to, you need to keep your record clean both to maintain your self-respect and to avoid gaining a reputation for slippery dealing. Second, as soon as you begin acting unethically, you lose the right to protest other people’s conduct. Their behavior may give you a legitimate claim to extract concessions, or it may form the basis for a legal case. Once you join them in the gutter, you forfeit your moral and legal advantage. Figure 11.1 is a tool to keep yourself out of trouble with deception. You’ll have to decide for yourself whether the advice on the chart passes muster under your personal ethical standards. So far as I know, all of the alternatives are legal, so Poker School adherents who find themselves in a tight spot in which a lie will not work should feel free to use them. Pragmatists usually prefer to avoid lies if relationships matter, so these will be helpful to them, too. Idealists can use any of these that involve telling the truth in a way that does not mislead or deflecting a question with an obvious, transparent blocking maneuver. Remember, there is no commandment in negotiation that says “Thou shalt answer every question that is asked.” And as an aspiring idealist, I have found it useful to follow this rule: Whenever you are tempted to lie about something, stop, think for a moment, and then find something—anything— to tell the truth about. If the other side asks you about your alternatives or your bottom line, deflect that question and then tell the truth about your goals, expectations, and interests. FIGURE 11.1 Alternatives to Lying A Rogue’s Gallery of Tactics As my final offering on this topic, here is a list of the more common manipulative tactics you will encounter at the bargaining table. We have seen some of these before, but I will summarize them again for ease of reference. Note that only some of them involve overt deception. I do not label these “unethical” because most of them are well within the boundaries of the Poker School and some can work even for pragmatists when there is no relationship problem in view. LIES ABOUT BOTTOM LINES AND ALTERNATIVES We’ve talked about these. They are the most common lies of all. Take any statements of this sort with a big grain of salt unless you know and trust the other party, or you have all the leverage and the other party’s claims about its alternatives don’t matter. LOWBALLING This is the “too good to be true” offer the car dealership tried to use on Singer. The other side gets you committed to the deal before revealing the full, true cost to you. After you say “yes,” they know you want what they are peddling and they work the price back in their favor by adding terms. Don’t think this technique works only in sales. Have you ever met a children’s soccer coach who got you to agree to let your child play on his team, only to find out that the team practices every evening at dinnertime and plays on Sundays at 6 A.M.? That’s a lowball encounter. PHONY ISSUES Negotiation guru Roger Dawson calls this the “Decoy” or “Red Herring” technique. One side lists four or five issues as being very important or even vital, when, in fact, only one or two matter. The rest are phony issues. That side pushes hard on the whole agenda, creating a serious risk of impasse, then relents on all the phony issues in exchange for major concessions on the issues that really matter. Here is an example of the phony issues ploy involving some people we have met before in this book. When Akio Morita’s Sony Corporation was in the middle of its $5 billion purchase of Columbia Pictures in 1989, it negotiated a $200 million side deal with Jon Peters and Peter Guber for Guber-Peters Entertainment to run Sony’s new movie division. There was just one problem: Guber and Peters were already under contract with Warner Bros. and Warner’s boss, Steve Ross. Guber and Peters assured Sony that they had an oral agreement that Ross would release them from their existing contract if the Sony-Columbia deal went through, but they were secretly worried that Ross might cause trouble (and they were right—Ross subsequently sued Sony for $1 billion over this issue). The Guber-Peters team needed to negotiate as much time as possible to fix the release. Guber and Peters threw three issues onto the table in the final round of bargaining over their proposed contract with Sony: two phony issues and the issue of the time they would get after the Sony-Columbia deal closed to obtain their release from Warner. They negotiated all night on all three issues. At 7 A.M., the Guber-Peters team made its final move: “On point number one, we give up,” said their attorney. “On point number two, we give up. On point number three—the timing—you should give up.” Sony relented and gave them a full month to get their release. FAKE AUTHORITY PLOYS Lies about authority take two forms. First, people will lie and say they have authority when they do not. That was essentially what the car salesman did when he mentioned the $8,500 price to Singer just after visiting the sales manager. These lies are usually in the service of a lowball maneuver. They are hard to combat. In general, when in any doubt, it pays to ask for proof of authority when the other side makes an offer. The second kind of lie involves people saying they have no authority when in fact they do. Lawyers and other agents and brokers do this a lot. If you make an offer that is within their authority, they will lie and say that they are not authorized to accept your offer because it is not high or low enough. The solution to this problem is to avoid dealing with agents if you can. Make your offers directly to the people who have the power to say “yes” or “no.” Finally, watch out for authority ploys in which the other side presents you with a dense contract of “standard terms” or claims the boss is asking everyone to agree. Defer to authority if you must, but make sure the authority is real. OVERCOMMITMENT Essentially, the other negotiator drags out the negotiation process and/or gets you to make an investment based on an assumption that it will go through. Then he raises or lowers the price or adds new terms at the last minute, trusting that you have too much invested to lose and so will say “yes.” The best antidote is to monitor your commitment and ask yourself if the other party is as invested as you are. GOOD GUY/BAD GUY It uses the contrast effect to make otherwise unreasonable terms and conditions look reasonable. The bad guy introduces outrageous and demanding terms. His teammate, the good guy, becomes your advocate and argues the bad guy down to a merely aggressive level. You and the good guy bond against the bad guy. In the end, you win the argument and lose the negotiation. The best way to fight this is to recognize it, name it, and refuse to go along with it. CONSISTENCY TRAPS Chapter 3 discusses this tactic. A consistency trap works as follows: The other negotiator gets you to agree to an innocent-sounding standard or norm. Then he springs the trap by showing you that his proposal is the logical consequence of your admission. The solution to a consistency trap is to see it coming before you agree to the standard and hedge your commitment to the standard. RECIPROCITY PLOYS When we negotiate, we take turns exchanging questions and answers and making concessions. Watch out for people who either refuse to reciprocate in the process or who only appear to do so without giving substantive answers. The norm of reciprocity entitles you to tit-for-tat treatment in bargaining. Insist on it. THE NIBBLE Parties nibble at an agreement just before closing. They raise an extra issue or demand that in and of itself is so small it does not seem worthy of debate. But they get this issue without trading for it, so it is pure profit. The dedicated nibbler can add 3 to 5 percent of value to his or her contracts this way. This tactic gains power from both the contrast effect and the overcommitment phenomenon. The antidote? Just say no. Or require something in trade for every concession requested by the nibbler. SummaryEthical dilemmas are at the center of many bargaining encounters. There is no escaping the fact that deception is part of negotiation. And there is no escaping the importance people place on personal integrity in their dealings with others at the bargaining table. One ethical slip and your credibility is lost not just for one but for many deals. Effective negotiators take the issue of personal integrity very seriously. Ineffective negotiators do not. How do you balance these two contradictory factors? I have presented three frameworks for thinking about ethical issues: the Poker School, the Idealist School, and the Pragmatist School. I personally think you are better off sticking to the truth as much as possible. I sometimes lose leverage as the price of this scruple, but I gain a greater measure of ease and self-respect as compensation. Where you come out on bargaining ethics, of course, is a matter for you to decide. My only injunction to you would be: Negotiators who value personal integrity can be counted on to behave consistently, using a thoughtful set of personal values that they could, if necessary, explain and defend to others. ETHICS: A CHECKLIST ✓ Decide which school of bargaining ethics you belong to. ✓ Determine whether you can use your relationships to offset the dangers of unethical conduct by others involved in the transaction. ✓ Probe, probe, probe. Don’t take what you hear at face value. ✓ Pause. Remember that you don’t have to answer every question. ✓ Don’t lie. Instead, find a way to use the truth to your advantage. CHAPTER 12 - Conclusion: On Becoming an Effective Negotiator Do not be so sweet that people will eat you up, nor so bitter that they will spit you out. —PASHTO FOLK SAYING Seven Tools for Highly Cooperative People If you are basically a cooperative, reasonable person, you need to become more assertive, confident, and prudent in negotiations to become more effective. How can you do this? It is sometimes the hardest thing in the world to gear up for a potentially confrontational negotiating situation. Here are seven specific tools to improve your bargaining performance. 1. Avoid concentrating too much on your bottom line—spend extra time preparing your goals and developing high expectations. As a cooperative person, you often worry about other people’s needs first. You focus on your bottom line and try to do just a little better than that. And guess what? Your bottom line is exactly what you get. Research confirms that people who expect more get more. Refocus your thinking on your goals and expectations. Spend extra time considering carefully what you want and why you want it. 2. Develop a specific alternative as a fallback if the negotiation fails. Too often, cooperative people leave themselves without choices at the bargaining table. They have no alternatives planned if negotiations fail. Take note: If you can’t walk away, you can’t say “no.” Remember the story about “Janie Rail” in Chapter 6. A Houston utilities buyer built her own railroad when the rail company she was doing business with refused to give her a competitive price for delivering coal. Lesson: There is always an alternative. Find out what it is and bring it with you to the bargaining table. You will feel more confident. 3. Get an agent and delegate the negotiation task. If you are up against competitive negotiators, you will be at a disadvantage. Find a more competitively oriented person to act as your agent or at least join your team. This is not an admission of failure or lack of skill. It is prudent and wise. 4. Bargain on behalf of someone or something else, not yourself. Even competitive people feel weaker when they are negotiating on their own behalf. Cooperative people think they are being selfishto insist on things coming out their way. Fine. Don’t negotiate for yourself. Stop for a moment and think about other people and causes— your family, your staff, even your future “retired self ”—that are depending on you to act as their agent and “bring home the bacon” in this negotiation. Then bargain on their behalf. Research shows that people bargain harder when they act as agents for others’ interests. 5. Create an audience. Research reveals that people negotiate more assertively when other people are watching them. That is why labor negotiators are so tough—they know the union rank and file is watching their every move. Take advantage of this effect. Tell someone you know about the negotiation. Explain your goals and how you intend to proceed. Promise to report to them on the results when the negotiation is over. 6. Say, “You’ll have to do better than that, because...” Cooperative people are programmed to say “yes” to almost any plausible proposal someone else makes. To improve, you need to practice pushing back a little when others make a bargaining move. A simple phrase that works is “You’ll have to do better than that, because...” (fill in a reason). The better the reason, the better you will feel about it but any truthful reason will do. Research shows that many people will respond favorably if you make a request in a reasonable tone of voice and accompany it with a “because” statement. In one famous study, a Harvard psychologist increased the compliance rate for requests by 50 to 100 percent just by giving a “dummy” reason when she made a request. She set up an experiment at a photocopy machine in the library and had her experimenters wait for a line to form, then try to cut into the line to make copies. When the requester had just five pages to copy, about 60 percent of the people said “yes” to the question “Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?” When the requestor had twenty pages to copy, the “yes” rate understandably dropped to 24 percent. Then the requestor added the phrase “because I’m in a rush” to the end of the request. Now it went like this: “Excuse me, I have five [or twenty] pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I’m in a rush?” The success rate leaped to 94 percent for the five-page request and a remarkable 42 percent for the twenty-page request. Try this technique at the store, at school, in the airport, on the telephone, everywhere. Then use it at the bargaining table. Remember, the better the reason, the better you will feel about it and the more likely you will be to achieve your goal. And try doing this the idealist way: Make the reason truthful. 7. Insist on commitments, not just agreements. Cooperative people think others are as goodhearted as they themselves are. They trust others more than is good for them, and they think an agreement is all that is needed to ensure that performance will take place as promised. Don’t be so trusting. Agreements are fine if you have a solid basis for believing that the other party’s word is its bond. But be sure you have that foundation before risking all the work you have invested in a negotiation. If you don’t know the people on the other side well or suspect that they may be untrustworthy, set the agreement up so they have something to lose if they fail to perform. Seven Tools for Highly Competitive People If you are basically a competitive but still reasonable person, you need more than anything to become more aware of other people and their legitimate needs. How can you do this? It issometimes the hardest thing in the world to overcome your inherent suspicion of others’ motives. And it is difficult to resist temptation when you are dealing with a cooperative person who is naively handing things to you. Here are seven specific tools you can use to improve your bargaining performance. 1. Think win-win, not just win. I know I said at the beginning of the book that win-win is an empty idea. It is—for accommodating and cooperative people. For competitive people, win-win is an excellent reminder that the other party matters. Go for deals in which both sides do better but you do the best of all. 2. Ask more questions than you think you should. Competitive people like to get enough information to see where an advantage might lie, then pounce and try to exploit the opening. Don’t be in such a hurry. Other people have a variety of needs; they do not always want the same things you do. If you can understand what is really important to them, they will give you more of what is important to you. 3. Rely on standards. Reasonable people respond well to arguments based on their standards and norms. Don’t be too quick to use a leverage-based approach to negotiation when a standards-based approach will work just as well. Reasoned arguments also work better than power plays when future relationships are important. 4. Hire a relationship manager. You will do better when the relationship matters if you delegate the relationship management aspect of the deal to someone who is better with people than you are. This is not a sign of failure; it is prudent and wise. 5. Be scrupulously reliable. Keep your word. You may have a tendency to cut corners when you see victory just ahead. But other people notice if you break your promises, even over little things. And they have memories like elephants. Establish a record of scrupulous reliability, and others will trust you more. A lot of money can be made when people trust each other. 6. Don’t haggle when you can negotiate. You are tempted to haggle over every issue and try to win each one. That is a sure way to leave money on the table in complex negotiations. Try integrative bargaining in complex situations: Make big moves on your little issues and little moves on your big ones. Manage your priorities. Package your trade-offs using the “If ... Then” formulation discussed in Chapter 9. 7. Always acknowledge the other party. Protect his or her self-esteem. People are proud. They like to hear you say they have some leverage, even when they do not. Don’t gloat when you are the more powerful party. Treat people on the other side with appropriate respect. This does not cost much, and they will appreciate it. Someday they will have the leverage, and they will remember you more kindly. SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF NEGOTIATORS EXHIBITING THE FIVE BARGAINING STYLES Over the years, I have discussed bargaining style profiles with thousands of executives and other professionals. In these conversations, I have tested various style-based hypotheses with them for confirmation or disconfirmation. Below I summarize this experience by commenting on the bargaining strengths and weaknesses that may be exhibited by negotiators in a relatively high (70th or higher) percentile or relatively low (30th or lower) percentile for each conflict mode. For shorthand, I refer to people with each trait by the name of the bargaining style itself (e.g., “high accommodator” or “low compromiser”). I am thus assuming in these comments that the person is “high” or “low” in the subject conflict style only—and “in the middle” for all other modes. This is a convenient rather than a realistic assumption, but it permits me to discuss some important implications of each trait. Individuals may exhibit strong or weak preferences for several strategies, and the interaction of these preferences will, of course, affect the way they experience and manage their bargaining behavior in any given situation. ACCOMMODATING Negotiators Strongly Predisposed toward Accommodating. Negotiators with a strong predisposition toward accommodation derive significant satisfaction from solving other peoples’ problems. They often have good relationship-building skills and are relatively sensitive to others’ emotional states, body language, and verbal signals. This is a great trait to summon when working on negotiating problems within teams, bargaining in sales-based “relationship management” roles, or providing many types of customer services. In terms of weaknesses, high accommodators sometimes place more weight on the relationship aspect of negotiations than the situation may warrant. In such cases, they are vulnerable to more competitively oriented people. High accommodators who feel taken advantage of in such situations may then experience resentment, further impeding their effectiveness. Weakly Predisposed toward Accommodating. Negotiators with low accommodation scores have atendency to hold out for their view of the “right” answer to a negotiating problem. They stay within their own frame of reference, seeing their solution as objectively correct. In short, low accommodators are sometimes more concerned with being “right” than with being persuasive. Where the low accommodator is an expert who understands the negotiation problem better than others at the table, this trait will assure that a group spends plenty of time considering the objectively “best” outcome. However, others may perceive the low accommodator as stubborn to the point of being unreasonable. This perception can interfere with effective group decision making. In addition, more accommodating people may mistake the low accommodator’s preoccupation with the “right” answer (and associated lack of attention to other people’s feelings and emotions) as a signal that the low accommodator does not care about them as individuals. Again, this can lower people’s willingness to cooperate. COMPROMISING Negotiators Strongly Predisposed toward Compromising. People with a strong predisposition toward compromising are usually eager to close the deal by “closing the gap” in negotiations. They scan the environment for fair standards and formulae that can help them achieve closure as quickly as possible. When time is short, or when the stakes are small, a predisposition toward compromise can be a virtue. Others will see the high compromiser as a relationship-friendly “reasonable person.” However, high compromisers often rush the negotiation process unnecessarily and make concessions too quickly. They do not question their own assumptions and rarely ask enough questions of the other side. They may also be satisfied with the first fair standard that presents itself as the basis for concluding the deal when other, equally fair standards might support a more advantageous deal. Weakly Predisposed toward Compromising. People with a weak predisposition for compromise are, almost by definition, men and women of principle. Their great strength is their ability to summon passion and commitment when serious matters of principle and precedent are at stake in a negotiation. Their great weakness is their tendency to “make an issue” of everything—finding issues of principle where others see only issues relating to money or relative convenience. By arguing at length about things others see as secondary, the low compromiser risks being seen by others as stubborn—a person who is more concerned with winning an argument than closing a deal. Their distaste for such arbitrary allocation norms as splitting the difference can also make it more difficult for the low compromiser to close a deal when time is short. A comparison between low accommodators and low compromisers is instructive. Low accommodators can (more quickly than most) become attached to their own preferred “correct” solutions. Low compromisers, by comparison, become attached to their own preferred “correct” principles and fairness arguments. In both cases, they may irritate other people, acquiring reputations for being stubborn. AVOIDING Negotiators Strongly Predisposed toward Avoiding. High avoiders are adept at deferring and dodging the confrontational aspects of negotiation. As a positive attribute, avoidance can beexperienced by others as graceful tact and diplomacy. It can also permit groups to function better in the face of dysfunctional, hard-to-resolve interpersonal differences. High avoiders are skilled at using such conflict-reducing methods as clear rules, unambiguous decision-making authority, and hierarchies to substitute for negotiations. High avoiders are also at home using techniques like e-mail, memos, hired agents, and other intermediaries that minimize the need for face-to-face confrontation. When interpersonal conflict is a functional aspect of organizational or group life, high avoiders can be a bottleneck in the flow of important information about the intensity of people’s preferences. And when interpersonal conflicts fester, they sometimes get worse, leading to all manner of problems. Finally, high avoiders pass up many opportunities to ask for things that would make them better off when others would be perfectly happy to accommodate their need. This may result in their becoming dissatisfied with a situation when a solution to meet their needs is only a question away. Weakly Predisposed toward Avoiding. Low avoiders have little fear of interpersonal conflict. Indeed, they may in some cases enjoy it. As negotiators, they have a high tolerance for assertive, candid bargaining. They can fight hard against their bargaining counterpart all day and share drinks and stories with the same person in the evening. Low avoidance scores are helpful in such professions as labor-management relations, litigation, and mergers and acquisitions work. But beware: People with low scores in avoiding sometimes lack tact, and are often viewed as overly confrontational. In bureaucratic settings, low avoiders may be seen as troublemakers who refuse to leave well enough alone. The low avoider is characteristically frustrated by bureaucracy and office politics, which are alien settings to him or her. COLLABORATING Negotiators Strongly Predisposed toward Collaborating. High collaborators enjoy negotiations because they enjoy solving tough problems in engaged, interactive ways. They are instinctively good at using negotiations to probe beneath the surface of conflicts to discover basic interests, perceptions, and new solutions. They relish the continuous flow of the negotiation process and encourage everyone to be involved. They are assertively and honestly committed to finding the best solution for everyone. By the same token, people with a strong predisposition for collaborating sometimes needlessly create problems by transforming relatively simple situations into more complex (and interesting) occasions to practice their skills. This can irritate other people who want closure, who lack time to invest in a matter, or who do not wish to risk triggering interpersonal conflict over a small, albeit nagging, issue. High collaborators also need other, less collaborative skills to claim their fair share of the gains they help create. A high collaborator with a very low competing score can be at risk against a highly competitive counterpart. Weakly Predisposed toward Collaborating. Low collaborators dislike using the bargaining process as a forum for creativity. These negotiators prefer having problems clearly specified before the negotiation begins and like to stick to the agenda and their preset goals once a meeting starts. They often bring a methodical pace, solid planning, and a need for clarity to their practice. When the matters being negotiated are so inherently complex that real-time brainstorming is the best way to proceed, low collaborators may become a bottleneck, slowing the process down. One way for low collaborators to compensate for this weakness is to make liberal use of breaks in the bargaining process to gather their thoughts and reset their strategy. COMPETING Negotiators Strongly Predisposed toward Competing. Like high collaborators, high competitors also enjoy negotiating. But they enjoy it for a different reason: Negotiating presents an opportunity for winning and losing, and they like to win. For this reason, high competitors prefer to frame negotiations as games with moves that can result in gains or losses, depending on one’s relative skill. Highly competitive negotiators have strong instincts about such matters as leverage, deadlines, how to open, how to position final offers, ultimata, and similar aspects of traditional negotiations. Competitors have energy and motivation in transactional negotiations in which the stakes are high. However, because their style can dominate the bargaining process, competitive people can be hard on relationships. The “loser” in a negotiating game, for example, may feel taken, coerced, or abused. This can affect future dealings. In addition, competitive negotiators instinctively focus on the issues that are easiest to count in terms of winning and losing—like money. They may overlook nonquantitative issues that can also yield value. Weak Predisposition toward Competing. People with a weak predisposition for competing do not think that negotiations are simply about winning and losing. They see negotiations as a dance, not a game. It is a dance in which the goal is for the parties to treat each other fairly, avoid needless conflict, solve problems, or create trusting relationships. Others often view people with low competing scores as especially nonthreatening. This can be a strength in many professional settings in which the ability to gain trust is a critical skill. However, when there are large stakes on the table, the low competitor will be at a disadvantage.