We will demonstrate distributed deep learning for the problem of anomaly detection.

The first step is to set up Elephas on Ubuntu OS.

The dependencies for Elephas are present in a file "req.txt" at the 'current working directory':

Flask==1.0.2

hyperas==0.4

pyspark==2.4.0

six==1.11.0

tensorflow==1.15.2

pydl4j>=0.1.3

keras==2.2.5

Next, we run following commands in Anaconda terminal:

conda create -n elephas python=3.7

conda activate elephas

pip install -r req.txt

pip install elephas ipykernal jupyter jupyterlab pandas matplotlib seaborn scikit-learn autoflake

python -m ipykernel install --user --name elephas

Check the elephas version:

(elephas) ashish@ashish-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$ pip show elephas

Name: elephas

Version: 0.4.3

Summary: Deep learning on Spark with Keras

Home-page: http://github.com/maxpumperla/elephas

Author: Max Pumperla

Author-email: max.pumperla@googlemail.com

License: MIT

Location: /home/ashish/anaconda3/envs/elephas/lib/python3.7/site-packages

Requires: hyperas, keras, cython, six, pyspark, tensorflow, flask

Required-by:

Python code from Jupyter Notebook:

from collections import Counter

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from pyspark import SparkContext

from elephas.spark_model import SparkModel

from elephas.utils.rdd_utils import to_simple_rdd

import keras

print("keras", keras.__version__)

import pyspark

print("pyspark", pyspark.__version__)

import tensorflow

print("tensorflow", tensorflow.__version__)

keras 2.2.5

pyspark 2.4.0

tensorflow 1.15.2

sc = SparkContext.getOrCreate()

df_iris = pd.read_csv('files_1/iris_flower/iris.data',

names = ['sepal_length', 'sepal_width', 'petal_length', 'petal_width', 'flower_class'])

for i in ['Iris-setosa', 'Iris-versicolor', 'Iris-virginica']:

print(i, ":")

print(df_iris[df_iris.flower_class == i].describe())

Iris-setosa :

sepal_length sepal_width petal_length petal_width

mean 5.00600 3.418000 1.464000 0.24400

min 4.30000 2.300000 1.000000 0.10000

max 5.80000 4.400000 1.900000 0.60000

Iris-versicolor :

sepal_length sepal_width petal_length petal_width

mean 5.936000 2.770000 4.260000 1.326000

min 4.900000 2.000000 3.000000 1.000000

max 7.000000 3.400000 5.100000 1.800000

Iris-virginica :

sepal_length sepal_width petal_length petal_width

mean 6.58800 2.974000 5.552000 2.02600

min 4.90000 2.200000 4.500000 1.40000

max 7.90000 3.800000 6.900000 2.50000

We will use the "max" values to introduce anomalies in the dataset.

df_iris_anomalies = pd.DataFrame({

"sepal_length": [7, 8, 9],

"sepal_width": [7, 4, 5],

"petal_length": [4, 6, 8],

"petal_width": [4, 3, 3],

"flower_class": ['Iris-setosa', 'Iris-versicolor', 'Iris-virginica']

})

df_iris = pd.concat([df_iris, df_iris_anomalies], axis = 0)

def frequency_encoder(input_df, column_name):

counter = 0

ranked_dict = {}

def ranker():

nonlocal counter

counter += 1

return counter

for i in Counter(input_df[column_name]).most_common():

ranked_dict[i[0]] = ranker()

return ranked_dict

ranked_dict = frequency_encoder(df_iris, column_name = 'flower_class')

df_iris['flower_class_enc'] = df_iris['flower_class'].apply(lambda x: ranked_dict[x])

X_train = df_iris[['sepal_length', 'sepal_width', 'petal_length', 'petal_width', 'flower_class_enc']]

Defining Model

act_func = 'tanh'

model = keras.Sequential()

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(5, activation=act_func, kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform',

input_shape=(X_train.shape[1],)))

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation=act_func, kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(5, activation=act_func, kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(X_train.shape[1], kernel_initializer='glorot_uniform'))

opt = keras.optimizers.Adam(lr=0.01)

model.compile(loss='mse', optimizer=opt, metrics=['accuracy'])

model.summary()

rdd = to_simple_rdd(sc, X_train, X_train)

spark_model = SparkModel(model, frequency='epoch', mode='asynchronous')

spark_model.fit(rdd, epochs=20, batch_size=32, verbose=0, validation_split=0.1)

Prediction

X_pred = spark_model.predict(np.array(X_train))

X_pred = pd.DataFrame(X_pred, columns=X_train.columns)

X_pred.index = X_train.index

scored = pd.DataFrame(index=X_train.index)

scored['Loss_mae'] = np.mean(np.abs(X_pred-X_train), axis = 1)

fraction_of_anomalies = 0.03

scores_threshold = scored['Loss_mae'].quantile([1 - fraction_of_anomalies])[1 - fraction_of_anomalies]

is_anomaly = scored['Loss_mae'] > scores_threshold

df_anomaly = X_train[is_anomaly]

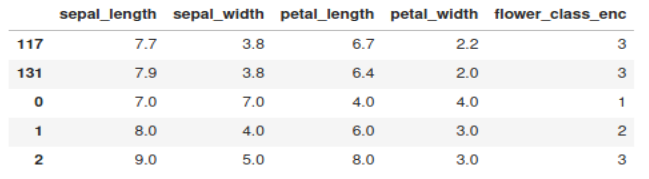

print(df_anomaly)

The three anomalies that we introduced in the dataset are appearing at the bottom.

Elephas Documentation: Github

Pages

- Index of Lessons in Technology

- Index of Book Summaries

- Index of Book Lists And Downloads

- Index For Job Interviews Preparation

- Index of "Algorithms: Design and Analysis"

- Python Course (Index)

- Data Analytics Course (Index)

- Index of Machine Learning

- Postings Index

- Index of BITS WILP Exam Papers and Content

- Lessons in Investing

- Index of Math Lessons

- Downloads

- Index of Management Lessons

- Book Requests

- Index of English Lessons

- Index of Medicines

- Index of Quizzes (Educational)

Friday, July 31, 2020

Distributed Deep Learning Using Python Packages Elephas, Keras, Tensorflow and PySpark

Sunday, July 26, 2020

Installing a new kernel in Jupyter Notebook in Anaconda with Python 3.8.3 on Ubuntu 20.04

Follow these steps in the Ubuntu "Terminal". Step 1: conda create -n py383 python=3.8.3 Step 2: conda activate py383 Step 3: pip install ipykernel Step 4: pip install jupyter Step 5: First, we get an error because we didn't specify that we want it for the current user through the argument "--user". (py383) ashish@ashish-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$ python -m ipykernel install --name py383 [Errno 13] Permission denied: '/usr/local/share/jupyter' (py383) ashish@ashish-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$ lsb_release -a No LSB modules are available. Distributor ID: Ubuntu Description: Ubuntu 20.04.1 LTS Release: 20.04 Codename: focal (py383) ashish@ashish-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$ python -m ipykernel install --user Installed kernelspec python3 in /home/ashish/.local/share/jupyter/kernels/python3 (py383) ashish@ashish-VirtualBox:~/Desktop$ python -m ipykernel install --user --name py383 Installed kernelspec py383 in /home/ashish/.local/share/jupyter/kernels/py383 Ref: ipython.readthedocs.io

Friday, July 24, 2020

Anomaly Detection using Scikit-Learn and "eif" PyPI package (for Extended Isolation Forest)

Definition Anomaly detection is the process of identifying unexpected items or events in data sets, which differ from the norm. And anomaly detection is often applied on unlabeled data which is known as unsupervised anomaly detection. Anomaly detection has two basic assumptions: • Anomalies only occur very rarely in the data. • Their features differ from the normal instances significantly. Novelty and Outlier Detection • Outlier detection (unsupervised anomaly detection) The training data contains outliers which are defined as observations that are far from the others. Outlier detection estimators thus try to fit the regions where the training data is the most concentrated, ignoring the deviant observations. • Novelty detection (semi-supervised anomaly detection) The training data is not polluted by outliers and we are interested in detecting whether a new observation is an outlier. In this context an outlier is also called a novelty. One-Class SVM SVM or “Support Vector Machine” is a supervised classification model. One-class SVM is its unsupervised sibling for use in Outlier Analysis. According to skLearn documentation: The sklearn.svm.OneClassSVM is known to be sensitive to outliers and thus does not perform very well for outlier detection. This estimator is best suited for novelty detection when the training set is not contaminated by outliers. That said, outlier detection in high-dimension, or without any assumptions on the distribution of the inlying data is very challenging, and a One-class SVM might give useful results in these situations depending on the value of its hyperparameters. Robust Covariance. Fitting an elliptic envelope. One common way of performing outlier detection is to assume that the regular data come from a known distribution (e.g. data are Gaussian distributed). From this assumption, we generally try to define the “shape” of the data, and can define outlying observations as observations which stand far enough from the fit shape. The scikit-learn provides an object “covariance.EllipticEnvelope” that fits a robust covariance estimate to the data, and thus fits an ellipse to the central data points, ignoring points outside the central mode. For instance, assuming that the inlier data are Gaussian distributed, it will estimate the inlier location and covariance in a robust way (i.e. without being influenced by outliers). The Mahalanobis distances obtained from this estimate is used to derive a measure of outlyingness. Isolation Forest One efficient way of performing outlier detection in high-dimensional datasets is to use random forests. The ensemble.IsolationForest ‘isolates’ observations by randomly selecting a feature and then randomly selecting a split value between the maximum and minimum values of the selected feature. Since recursive partitioning can be represented by a tree structure, the number of splittings required to isolate a sample is equivalent to the path length from the root node to the terminating node. This path length, averaged over a forest of such random trees, is a measure of normality and our decision function. Random partitioning produces noticeably shorter paths for anomalies. Hence, when a forest of random trees collectively produce shorter path lengths for particular samples, they are highly likely to be anomalies. The implementation of ensemble.IsolationForest is based on an ensemble of tree.ExtraTreeRegressor. Idea Behind Isolation Forest Decision Boundary With Isolation Forest Local Outlier Factor Another efficient way to perform outlier detection on moderately high dimensional datasets is to use the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) algorithm. The neighbors.LocalOutlierFactor (LOF) algorithm computes a score (called local outlier factor) reflecting the degree of abnormality of the observations. It measures the local density deviation of a given data point with respect to its neighbors. The idea is to detect the samples that have a substantially lower density than their neighbors. In practice the local density is obtained from the k-nearest neighbors. The LOF score of an observation is equal to the ratio of the average local density of his k-nearest neighbors, and its own local density: a normal instance is expected to have a local density similar to that of its neighbors, while abnormal data are expected to have much smaller local density. The number k of neighbors considered, (alias parameter n_neighbors) is typically chosen 1) greater than the minimum number of objects a cluster has to contain, so that other objects can be local outliers relative to this cluster, and 2) smaller than the maximum number of close by objects that can potentially be local outliers. In practice, such informations are generally not available, and taking n_neighbors=20 appears to work well in general. When the proportion of outliers is high (i.e. greater than 10 %, as in the example below), n_neighbors should be greater (n_neighbors=35 in the example below). The strength of the LOF algorithm is that it takes both local and global properties of datasets into consideration: it can perform well even in datasets where abnormal samples have different underlying densities. The question is not, how isolated the sample is, but how isolated it is with respect to the surrounding neighborhood. Local Outlier Factor: Detect the samples that have a substantially lower density than their neighbors. Outside of skLearn but an important development is the algorithm: “Extended Isolation Forest” Isolation Forest algorithm utilizes the fact that anomalous observations are few and significantly different from ‘normal’ observations. The forest is built based on the decision trees, each of the trees having access to a sub-sample of the training data. In order to create a branch in the tree, first, a random feature is selected. Afterward, a random split value (between min and max value) is chosen for that feature. If the given observation has a lower value of this feature than the one selected, then the observation follows the left branch, otherwise the right one. This process is continued until a single point is isolated or specified maximum depth is reached. Isolation Forest in Action In principle, outliers are less frequent than regular observations and are different from them in terms of values (they lie further away from the regular observations in the feature space). That is why by using such random partitioning they should be identified closer to the root of the tree (shorter average path length, i.e., the number of edges an observation must pass in the tree going from the root to the terminal node), with fewer splits necessary. The anomaly score is created based on all trees in the forest and the depth the point reaches in these trees. Isolation Forest’s Problem In the left picture below, we can see data sampled from the multivariate normal distribution. Intuitively, we would assume that the anomaly score assigned to the observations would increase radially from the central point of the distribution [0, 0]. However, this is clearly not the case, as seen in the right image. What is more, there are also rectangular artifacts of a lower score, such as the vertical one between point 0 and 1 on the x-axis. Let’s move on to the second example. Here we see two blobs centered at points [0, 10] and [10, 0]. By inspecting the right figure we see not only the artifacts that were present before, but also two ghost clusters (approximately at [0, 0] and [10, 10]). The reason for this peculiar behavior originates from the fact that the decision boundaries of the Isolation Forest are either vertical or horizontal (random value of a random feature), as seen in the picture below, where the authors plot branch cuts generated by the IF during the training phase. We see that the branches tend to cluster where majority of the points are located. But as the lines can only be parallel to the axes, there are regions that contain many branch cuts and only a few or single observations, which results in improper anomaly scores for some of the observations. An example might be in single blob figure where there are points around [3, 0] (many branch cuts) and [3, 3] (few cuts). Extended Isolation Forest Analysis of the Isolation Forest’s drawback led to the conclusion that the problem is caused by only horizontal/vertical branch cuts. Extended Random Forest addresses that issue by approaching the problem a bit differently. Instead of selecting a random feature and then random value within the range of data it selects: - the random slope for the branch cut - random intercept chosen from the range of available values from the training data - These are the terms (slope/intercept) you most likely recall from the simple linear regression (y = ax + b). Let’s look at a visual example! From the image below we can see the main difference from the original IF algorithm -> cuts that are not parallel to the axes. Extended Random Forest generalizes well into higher dimensions, where instead of straight lines we are dealing with hyperplanes. For a deeper dive into N-dimensional generalization, refer this paper. Let’s wrap up the theoretical explanation by looking at the difference in the anomaly score maps generated by IF/EIF. In the images below we see that the anomaly score spreads out from the data clusters radially and there are no artifacts/ghost clusters visible. An extra feature captured by the EIF is the higher anomaly score region directly in-between the two clusters (where they kind of link). This region can be considered as close to ‘normal’ given the proximity to both clusters, but with a higher score, as it is far from the concentrated groups. Caveat: "eif" implementations are way slower than skLearn implementation of Isolation Forest. For a test task, skLearn Iolation Forest took 14s to train, while the "eif" took roughly 10 minutes. References % towardsdatascience % Extended Isolation Forest % Novelty and Outlier Detection (scikit-learn.org/stable) % Comparing anomaly detection algorithms for outlier detection on toy datasets (scikit-learn.org/0.20) % Outlier detection with Local Outlier Factor (LOF) [scikit-learn.org/stable] % skLearn v0.23

Sunday, July 19, 2020

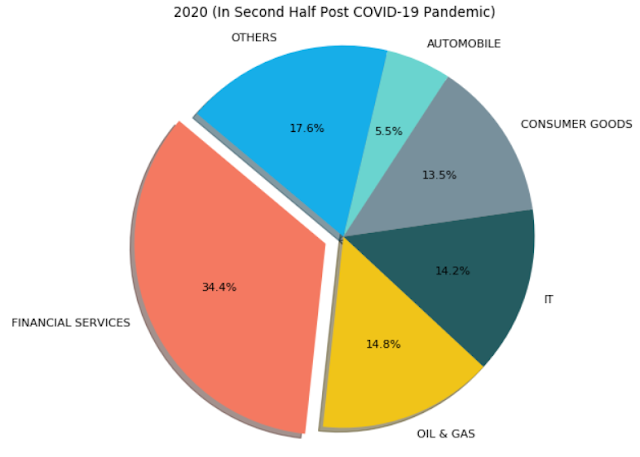

Plotting changes in Nifty50's top-5 sectors after last three market crashes

In this post we draw Pie plots, Bar charts and Grouped Bar Chart to visualize how top-5 sectors of Nifty50 have changes after last three market crashes:Drawing the Pie plots

import pandas as pd import matplotlib.pyplot as plt pd_00 = pd.DataFrame({ "Sector": ['CONSUMER GOODS', 'OIL & GAS', 'IT', 'FINANCIAL SERVICES', 'PHARMA'], "Weightage": [27.5, 24.2, 12.2, 10.1, 7.2] }) pd_08 = pd.DataFrame({ "Sector": ['OIL & GAS', 'TELECOM', 'FINANCIAL SERVICES', 'POWER', 'CONSTRUCTION'], "Weightage": [19.3, 9.7, 8.9, 5.5, 3.6] }) pd_20 = pd.DataFrame({ "Sector": ['FINANCIAL SERVICES', 'OIL & GAS', 'IT', 'CONSUMER GOODS', 'AUTOMOBILE'], "Weightage": [34.4, 14.8, 14.2, 13.5, 5.5] }) def add_others_col(df): return pd.concat([df, pd.DataFrame({'Sector': ['OTHERS'], 'Weightage': [(100 - sum(df.Weightage.values))] })], axis = 0) pd_00 = add_others_col(pd_00) pd_08 = add_others_col(pd_08) pd_20 = add_others_col(pd_20) def plot_pie(labels, sizes, title = ""): colors = ['#f47961', '#f0c419', '#255c61', '#78909c', '#6ad4cf', '#17aee8', '#5c6bc0', '#444b6e', '#ef4c60', '#744593', '#ee5691', '#9ccc65', '#708b75', '#d1cb65', '#0d8de1', '#a4554b', '#694f5d', '#45adb3', '#26a69a', '#bdc7cc', ] colors = colors[0:len(labels)] explode = (0.1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0) # explode 1st slice explode = explode[0:len(labels)] # Plot plt.figure(num=None, figsize=(9, 7), dpi=80, facecolor='w', edgecolor='k') plt.pie(sizes, explode=explode, labels=labels, colors=colors, autopct='%1.1f%%', shadow=True, startangle=140) plt.title(title) plt.axis('equal') plt.show() plot_pie(pd_00.Sector.values, pd_00.Weightage.values, '2000 (Dot Com Bubble)') plot_pie(pd_08.Sector.values, pd_08.Weightage.values, '2008 (Lehman Crisis)') plot_pie(pd_20.Sector.values, pd_20.Weightage.values, '2020 (In Second Half Post COVID-19 Pandemic)')

Drawing the Bar Charts

def plot_bar_graph(categories, values, title = "", xlabel = 'Sectors', ylabel = 'Weightage', figsize = (10, 8)): colors = ['#f47961', '#f0c419', '#255c61', '#78909c', '#6ad4cf', '#17aee8', '#5c6bc0', '#444b6e', '#ef4c60', '#744593', '#ee5691', '#9ccc65', '#708b75', '#d1cb65', '#0d8de1', '#a4554b', '#694f5d', '#45adb3', '#26a69a', '#bdc7cc', ] colors = colors[0:len(categories)] fig = plt.figure(figsize = figsize) ax = fig.add_axes([0,0,1,1]) barlist = ax.bar(categories, values) for i in range(len(barlist)): barlist[i].set_color(colors[i]) plt.xticks(rotation=70) plt.title(title) plt.xlabel(xlabel) plt.ylabel(ylabel) plot_bar_graph(pd_00.Sector.values, pd_00.Weightage.values, title = '2000 (Dot Com Bubble)', figsize = (7, 5)) plot_bar_graph(pd_08.Sector.values, pd_08.Weightage.values, title = '2008 (Lehman Crisis)', figsize = (7, 5)) plot_bar_graph(pd_20.Sector.values, pd_20.Weightage.values, title = '2020 (In Second Half Post COVID-19 Pandemic)', figsize = (7, 5))

Drawing the Grouped Bar Charts

import matplotlib import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import numpy as np def autolabel(rects, ax): """Attach a text label above each bar in *rects*, displaying its height.""" for rect in rects: height = rect.get_height() ax.annotate('{}'.format(height), xy=(rect.get_x() + rect.get_width() / 2, height), xytext=(0, 3), # 3 points vertical offset textcoords="offset points", ha='center', va='bottom') def plot_grouped_bar_graph(xlabels, values, group_lables): x = np.arange(len(values[0])) # the label locations width = 0.2 # the width of the bars fig, ax = plt.subplots() rects = [] for i in range(len(group_lables)): rects += [ax.bar(x + (i * width), values[i], width, label = group_lables[i])] # Add some text for labels, title and custom x-axis tick labels, etc. ax.set_ylabel('Weightage') ax.set_title('Nifty50 Composition as Industry Sectors Across Market Crashes') ax.set_xticks(x) ax.set_xticklabels(xlabels) ax.legend() for i in range(len(rects)): autolabel(rects[i], ax) fig.tight_layout() plt.show() group_lables = ['OIL & GAS', 'FINANCIAL SERVICES'] plot_grouped_bar_graph( xlabels = ['2000', '2008', '2020'], values = [ [pd_00[pd_00.Sector == 'OIL & GAS']['Weightage'].values[0], pd_08[pd_08.Sector == 'OIL & GAS']['Weightage'].values[0], pd_20[pd_20.Sector == 'OIL & GAS']['Weightage'].values[0]], [pd_00[pd_00.Sector == 'FINANCIAL SERVICES']['Weightage'].values[0], pd_08[pd_08.Sector == 'FINANCIAL SERVICES']['Weightage'].values[0], pd_20[pd_20.Sector == 'FINANCIAL SERVICES']['Weightage'].values[0]] ], group_lables = group_lables ) The two sectors that have continued to be in top 5 across these years are 'Oil and Gas' and 'Financial Services':

Changes in Nifty50's major sectors after last three market crashes since year 2000

Nifty50's Sectoral Leadership has changed in the past with every Crisis. How the Nifty50 top-5 sectors' contribution looked in 2000 (after the Dot Com Bubble):

How the Nifty50 sectors' contribution looked in 2008 (after the Lehman Crisis):

How the Nifty50 sectors' contribution looked in 2020 (around July as the Coronavirus Pandemic Curve was flattening):

The two sectors that have continued to be in top 5 across these years are 'Oil and Gas' and 'Financial Services':

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. A counter intuitive approach to living a good life. (Mark Manson)

CHAPTER 1: Don’t Try

Self-improvement and success often occur together. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the same thing. Our culture today is obsessively focused on unrealistically positive expectations: Be happier. Be healthier. Be the best, better than the rest. Be smarter, faster, richer, sexier, more popular, more productive, more envied, and more admired. Be perfect and amazing and crap out twelve-karat-gold nuggets before breakfast each morning while kissing your selfie-ready spouse and two and a half kids goodbye. Then fly your helicopter to your wonderfully fulfilling job, where you spend your days doing incredibly meaningful work that’s likely to save the planet one day. But when you stop and really think about it, conventional life advice—all the positive and happy self-help stuff we hear all the time—is actually fixating on what you lack. It lasers in on what you perceive your personal shortcomings and failures to already be, and then emphasizes them for you. You learn about the best ways to make money because you feel you don’t have enough money already. You stand in front of the mirror and repeat affirmations saying that you’re beautiful because you feel as though you’re not beautiful already. You follow dating and relationship advice because you feel that you’re unlovable already. You try goofy visualization exercises about being more successful because you feel as though you aren’t successful enough already. Ironically, this fixation on the positive—on what’s better, what’s superior— only serves to remind us over and over again of what we are not, of what we lack, of what we should have been but failed to be. After all, no truly happy person feels the need to stand in front of a mirror and recite that she’s happy. She just is. There’s a saying in Texas: “The smallest dog barks the loudest.” A confident man doesn’t feel a need to prove that he’s confident. A rich woman doesn’t feel a need to convince anybody that she’s rich. Either you are or you are not. And if you’re dreaming of something all the time, then you’re reinforcing the same unconscious reality over and over: that you are not that. Everyone and their TV commercial wants you to believe that the key to a good life is a nicer job, or a more rugged car, or a prettier girlfriend, or a hot tub with an inflatable pool for the kids. The world is constantly telling you that the path to a better life is more, more, more—buy more, own more, make more, fuck more, be more. You are constantly bombarded with messages to give a fuck about everything, all the time. Give a fuck about a new TV. Give a fuck about having a better vacation than your coworkers. Give a fuck about buying that new lawn ornament. Give a fuck about having the right kind of selfie stick. Why? My guess: because giving a fuck about more stuff is good for business. And while there’s nothing wrong with good business, the problem is that giving too many fucks is bad for your mental health. It causes you to become overly attached to the superficial and fake, to dedicate your life to chasing a mirage of happiness and satisfaction. The key to a good life is not giving a fuck about more; it’s giving a fuck about less, giving a fuck about only what is true and immediate and important. The Feedback Loop from Hell There’s an insidious quirk to your brain that, if you let it, can drive you absolutely batty. Tell me if this sounds familiar to you: You get anxious about confronting somebody in your life. That anxiety cripples you and you start wondering why you’re so anxious. Now you’re becoming anxious about being anxious. Oh no! Doubly anxious! Now you’re anxious about your anxiety, which is causing more anxiety. Quick, where’s the whiskey? Or let’s say you have an anger problem. You get pissed off at the stupidest, most inane stuff, and you have no idea why. And the fact that you get pissed off so easily starts to piss you off even more. And then, in your petty rage, you realize that being angry all the time makes you a shallow and mean person, and you hate this; you hate it so much that you get angry at yourself. Now look at you: you’re angry at yourself getting angry about being angry. Fuck you, wall. Here, have a fist. Or you’re so worried about doing the right thing all the time that you become worried about how much you’re worrying. Or you feel so guilty for every mistake you make that you begin to feel guilty about how guilty you’re feeling. Or you get sad and alone so often that it makes you feel even more sad and alone just thinking about it. Welcome to the Feedback Loop from Hell. ~ ~ ~ Here’s the thing that’s wrong with all of the “How to Be Happy” shit that’s been shared eight million times on Facebook in the past few years—here’s what nobody realizes about all of this crap: The desire for more positive experience is itself a negative experience. And, paradoxically, the acceptance of one’s negative experience is itself a positive experience. This is a total mind-fuck. So I’ll give you a minute to unpretzel your brain and maybe read that again: Wanting positive experience is a negative experience; accepting negative experience is a positive experience. It’s what the philosopher Alan Watts used to refer to as “the backwards law”—the idea that the more you pursue feeling better all the time, the less satisfied you become, as pursuing something only reinforces the fact that you lack it in the first place. The more you desperately want to be rich, the more poor and unworthy you feel, regardless of how much money you actually make. The more you desperately want to be sexy and desired, the uglier you come to see yourself, regardless of your actual physical appearance. The more you desperately want to be happy and loved, the lonelier and more afraid you become, regardless of those who surround you. The more you want to be spiritually enlightened, the more self-centered and shallow you become in trying to get there. % Everything worthwhile in life is won through surmounting the associated negative experience. % When you give too many fucks—when you give a fuck about everyone and everything—you will feel that you’re perpetually entitled to be comfortable and happy at all times, that everything is supposed to be just exactly the fucking way you want it to be. This is a sickness. And it will eat you alive. You will see every adversity as an injustice, every challenge as a failure, every inconvenience as a personal slight, every disagreement as a betrayal. You will be confined to your own petty, skull-sized hell, burning with entitlement and bluster, running circles around your very own personal Feedback Loop from Hell, in constant motion yet arriving nowhere. The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck So what does not giving a fuck mean? Let’s look at three “subtleties” that should help clarify the matter. Subtlety #1: Not giving a fuck does not mean being indifferent; it means being comfortable with being different. Subtlety #2: To not give a fuck about adversity, you must first give a fuck about something more important than adversity. Subtlety #3: Whether you realize it or not, you are always choosing what to give a fuck about.CHAPTER 2: Happiness Is a Problem

The Misadventures of Disappointment Panda You may salivate at the thought of a problem-free life full of everlasting happiness and eternal compassion, but back here on earth the problems never cease. Seriously, problems don’t end. Problems never fucking go away, he said—they just improve. Warren Buffett’s got money problems; the drunk hobo down at Kwik-E Mart’s got money problems. Buffett’s just got better money problems than the hobo. All of life is like this. Life is essentially an endless series of problems. The solution to one problem is merely the creation of the next one. Don’t hope for a life without problems. There’s no such thing. Instead, hope for a life full of good problems. Happiness Comes from Solving Problems Problems never stop; they merely get exchanged and/or upgraded. Happiness comes from solving problems. The keyword here is “solving.” If you’re avoiding your problems or feel like you don’t have any problems, then you’re going to make yourself miserable. If you feel like you have problems that you can’t solve, you will likewise make yourself miserable. The secret sauce is in the solving of the problems, not in not having problems in the first place. To be happy we need something to solve. Happiness is therefore a form of action; it’s an activity, not something that is passively bestowed upon you, not something that you magically discover in a top-ten article on the Huffington Post or from any specific guru or teacher. It doesn’t magically appear when you finally make enough money to add on that extra room to the house. You don’t find it waiting for you in a place, an idea, a job—or even a book, for that matter. Happiness is a constant work-in-progress, because solving problems is a constant work-in-progress—the solutions to today’s problems will lay the foundation for tomorrow’s problems, and so on. True happiness occurs only when you find the problems you enjoy having and enjoy solving. Sometimes those problems are simple: eating good food, traveling to some new place, winning at the new video game you just bought. Other times those problems are abstract and complicated: fixing your relationship with your mother, finding a career you can feel good about, developing better friendships. Whatever your problems are, the concept is the same: solve problems; be happy. Unfortunately, for many people, life doesn’t feel that simple. That’s because they fuck things up in at least one of two ways: 1. Denial. Some people deny that their problems exist in the first place. And because they deny reality, they must constantly delude or distract themselves from reality. This may make them feel good in the short term, but it leads to a life of insecurity, neuroticism, and emotional repression. 2. Victim Mentality. Some choose to believe that there is nothing they can do to solve their problems, even when they in fact could. Victims seek to blame others for their problems or blame outside circumstances. This may make them feel better in the short term, but it leads to a life of anger, helplessness, and despair. People deny and blame others for their problems for the simple reason that it’s easy and feels good, while solving problems is hard and often feels bad. Forms of blame and denial give us a quick high. They are a way to temporarily escape our problems, and that escape can provide us a quick rush that makes us feel better. Highs come in many forms. Whether it’s a substance like alcohol, the moral righteousness that comes from blaming others, or the thrill of some new risky adventure, highs are shallow and unproductive ways to go about one’s life. Much of the self-help world is predicated on peddling highs to people rather than solving legitimate problems. Many self-help gurus teach you new forms of denial and pump you up with exercises that feel good in the short term, while ignoring the underlying issue. Remember, nobody who is actually happy has to stand in front of a mirror and tell himself that he’s happy. Highs also generate addiction. The more you rely on them to feel better about your underlying problems, the more you will seek them out. In this sense, almost anything can become addictive, depending on the motivation behind using it. We all have our chosen methods to numb the pain of our problems, and in moderate doses there is nothing wrong with this. But the longer we avoid and the longer we numb, the more painful it will be when we finally do confront our issues. Emotions Are Overrated An obsession and overinvestment in emotion fails us for the simple reason that emotions never last. Whatever makes us happy today will no longer make us happy tomorrow, because our biology always needs something more. A fixation on happiness inevitably amounts to a never-ending pursuit of “something else”—a new house, a new relationship, another child, another pay raise. And despite all of our sweat and strain, we end up feeling eerily similar to how we started: inadequate. Psychologists sometimes refer to this concept as the “hedonic treadmill”: the idea that we’re always working hard to change our life situation, but we actually never feel very different. This is why our problems are recursive and unavoidable. The person you marry is the person you fight with. The house you buy is the house you repair. The dream job you take is the job you stress over. Everything comes with an inherent sacrifice—whatever makes us feel good will also inevitably make us feel bad. What we gain is also what we lose. What creates our positive experiences will define our negative experiences. This is a difficult pill to swallow. We like the idea that there’s some form of ultimate happiness that can be attained. We like the idea that we can alleviate all of our suffering permanently. We like the idea that we can feel fulfilled and satisfied with our lives forever. But we cannot. Choose Your Struggle If I ask you, “What do you want out of life?” and you say something like, “I want to be happy and have a great family and a job I like,” your response is so common and expected that it doesn’t really mean anything. Everybody enjoys what feels good. Everyone wants to live a carefree, happy, and easy life, to fall in love and have amazing sex and relationships, to look perfect and make money and be popular and well-respected and admired and a total baller to the point that people part like the Red Sea when they walk into the room. Everybody wants that. It’s easy to want that. A more interesting question, a question that most people never consider, is, “What pain do you want in your life? What are you willing to struggle for?” Because that seems to be a greater determinant of how our lives turn out. Happiness requires struggle. It grows from problems. Joy doesn’t just sprout out of the ground like daisies and rainbows. Real, serious, lifelong fulfillment and meaning have to be earned through the choosing and managing of our struggles. Whether you suffer from anxiety or loneliness or obsessivecompulsive disorder or a dickhead boss who ruins half of your waking hours every day, the solution lies in the acceptance and active engagement of that negative experience—not the avoidance of it, not the salvation from it. People want an amazing physique. But you don’t end up with one unless you legitimately appreciate the pain and physical stress that come with living inside a gym for hour upon hour, unless you love calculating and calibrating the food you eat, planning your life out in tiny plate–sized portions. People want to start their own business. But you don’t end up a successful entrepreneur unless you find a way to appreciate the risk, the uncertainty, the repeated failures, the insane hours devoted to something that may earn absolutely nothing. People want a partner, a spouse. But you don’t end up attracting someone amazing without appreciating the emotional turbulence that comes with weathering rejections, building the sexual tension that never gets released, and staring blankly at a phone that never rings. It’s part of the game of love. You can’t win if you don’t play. What determines your success isn’t, “What do you want to enjoy?” The relevant question is, “What pain do you want to sustain?” The path to happiness is a path full of shitheaps and shame. You have to choose something. You can’t have a pain-free life. It can’t all be roses and unicorns all the time. Pleasure is the easy question. And pretty much all of us have a similar answer. The more interesting question is the pain. What is the pain that you want to sustain? That’s the hard question that matters, the question that will actually get you somewhere. It’s the question that can change a perspective, a life. It’s what makes me, me, and you, you. It’s what defines us and separates us and ultimately brings us together.CHAPTER 3: You Are Not Special

...Entitlement is a failed strategy. It’s just another high. It’s not happiness. The true measurement of self-worth is not how a person feels about her positive experiences, but rather how she feels about her negative experiences. A person may hide from his problems by making up imagined successes for himself at every turn. And because he can’t face his problems, no matter how good he feels about himself, he is weak. A person who actually has a high self-worth is able to look at the negative parts of his character frankly—“Yes, sometimes I’m irresponsible with money,” “Yes, sometimes I exaggerate my own successes,” “Yes, I rely too much on others to support me and should be more self-reliant”—and then acts to improve upon them. But entitled people, because they are incapable of acknowledging their own problems openly and honestly, are incapable of improving their lives in any lasting or meaningful way. They are left chasing high after high and accumulate greater and greater levels of denial. But eventually reality must hit, and the underlying problems will once again make themselves clear. It’s just a question of when, and how painful it will be. Things Fall Apart The deeper the pain, the more helpless we feel against our problems, and the more entitlement we adopt to compensate for those problems. This entitlement plays out in one of two ways: 1. I’m awesome and the rest of you all suck, so I deserve special treatment. 2. I suck and the rest of you are all awesome, so I deserve special treatment. Opposite mindset on the outside, but the same selfish creamy core in the middle. In fact, you will often see entitled people flip back and forth between the two. Either they’re on top of the world or the world is on top of them, depending on the day of the week, or how well they’re doing with their particular addiction at that moment. The Tyranny of Exceptionalism Most of us are pretty average at most things we do. Even if you’re exceptional at one thing, chances are you’re average or below average at most other things. That’s just the nature of life. To become truly great at something, you have to dedicate shit-tons of time and energy to it. And because we all have limited time and energy, few of us ever become truly exceptional at more than one thing, if anything at all. We can then say that it’s a statistical improbability that any single person will be an extraordinary performer in all areas of life, or even in many areas of their life. Brilliant businesspeople are often fuckups in their personal lives. Extraordinary athletes are often shallow and as dumb as a lobotomized rock. Many celebrities are probably just as clueless about life as the people who gawk at them and follow their every move. We’re all, for the most part, pretty average people. But it’s the extremes that get all of the publicity. We kind of know this already, but we rarely think and/or talk about it, and we certainly never discuss why this could be a problem. Having the Internet, Google, Facebook, YouTube, and access to five hundred–plus channels of television is amazing. But our attention is limited. There’s no way we can process the tidal waves of information flowing past us constantly. Therefore, the only zeroes and ones that break through and catch our attention are the truly exceptional pieces of information—those in the 99.999th percentile. All day, every day, we are flooded with the truly extraordinary. The best of the best. The worst of the worst. The greatest physical feats. The funniest jokes. The most upsetting news. The scariest threats. Nonstop. Our lives today are filled with information from the extremes of the bell curve of human experience, because in the media business that’s what gets eyeballs, and eyeballs bring dollars. That’s the bottom line. Yet the vast majority of life resides in the humdrum middle. The vast majority of life is unextraordinary, indeed quite average. This flood of extreme information has conditioned us to believe that exceptionalism is the new normal. And because we’re all quite average most of the time, the deluge of exceptional information drives us to feel pretty damn insecure and desperate, because clearly we are somehow not good enough. So more and more we feel the need to compensate through entitlement and addiction. We cope the only way we know how: either through self-aggrandizing or through other-aggrandizing. Some of us do this by cooking up get-rich-quick schemes. Others do it by taking off across the world to save starving babies in Africa. Others do it by excelling in school and winning every award. Others do it by shooting up a school. Others do it by trying to have sex with anything that talks and breathes. This ties in to the growing culture of entitlement that I talked about earlier. Millennials often get blamed for this cultural shift, but that’s likely because millennials are the most plugged-in and visible generation. In fact, the tendency toward entitlement is apparent across all of society. And I believe it’s linked to mass-media-driven exceptionalism. The problem is that the pervasiveness of technology and mass marketing is screwing up a lot of people’s expectations for themselves. The inundation of the exceptional makes people feel worse about themselves, makes them feel that they need to be more extreme, more radical, and more self-assured to get noticed or even matter. When I was a young man, my insecurities around intimacy were exacerbated by all the ridiculous narratives of masculinity circulating throughout pop culture. And those same narratives are still circulating: to be a cool guy, you have to party like a rock star; to be respected, you have to be admired by women; sex is the most valuable thing a man can attain, and it’s worth sacrificing anything (including your own dignity) to get it. This constant stream of unrealistic media dogpiles onto our existing feelings of insecurity, by overexposing us to the unrealistic standards we fail to live up to. Not only do we feel subjected to unsolvable problems, but we feel like losers because a simple Google search shows us thousands of people without those same problems. Technology has solved old economic problems by giving us new psychological problems. The Internet has not just open-sourced information; it has also open-sourced insecurity, self-doubt, and shame. B-b-b-but, If I’m Not Going to Be Special or Extraordinary, What’s the Point? It has become an accepted part of our culture today to believe that we are all destined to do something truly extraordinary. Celebrities say it. Business tycoons say it. Politicians say it. Even Oprah says it (so it must be true). Each and every one of us can be extraordinary. We all deserve greatness. The fact that this statement is inherently contradictory—after all, if everyone were extraordinary, then by definition no one would be extraordinary—is missed by most people. And instead of questioning what we actually deserve or don’t deserve, we eat the message up and ask for more. Being “average” has become the new standard of failure. The worst thing you can be is in the middle of the pack, the middle of the bell curve. When a culture’s standard of success is to “be extraordinary,” it then becomes better to be at the extreme low end of the bell curve than to be in the middle, because at least there you’re still special and deserve attention. Many people choose this strategy: to prove to everyone that they are the most miserable, or the most oppressed, or the most victimized. A lot of people are afraid to accept mediocrity because they believe that if they accept it, they’ll never achieve anything, never improve, and that their life won’t matter. This sort of thinking is dangerous. Once you accept the premise that a life is worthwhile only if it is truly notable and great, then you basically accept the fact that most of the human population (including yourself) sucks and is worthless. And this mindset can quickly turn dangerous, to both yourself and others. The rare people who do become truly exceptional at something do so not because they believe they’re exceptional. On the contrary, they become amazing because they’re obsessed with improvement. And that obsession with improvement stems from an unerring belief that they are, in fact, not that great at all. It’s anti-entitlement. People who become great at something become great because they understand that they’re not already great—they are mediocre, they are average—and that they could be so much better. All of this “every person can be extraordinary and achieve greatness” stuff is basically just jerking off your ego. It’s a message that tastes good going down, but in reality is nothing more than empty calories that make you emotionally fat and bloated, the proverbial Big Mac for your heart and your brain. The ticket to emotional health, like that to physical health, comes from eating your veggies—that is, accepting the bland and mundane truths of life: truths such as “Your actions actually don’t matter that much in the grand scheme of things” and “The vast majority of your life will be boring and not noteworthy, and that’s okay.” This vegetable course will taste bad at first. Very bad. You will avoid accepting it. But once ingested, your body will wake up feeling more potent and more alive. After all, that constant pressure to be something amazing, to be the next big thing, will be lifted off your back. The stress and anxiety of always feeling inadequate and constantly needing to prove yourself will dissipate. And the knowledge and acceptance of your own mundane existence will actually free you to accomplish what you truly wish to accomplish, without judgment or lofty expectations. You will have a growing appreciation for life’s basic experiences: the pleasures of simple friendship, creating something, helping a person in need, reading a good book, laughing with someone you care about. Sounds boring, doesn’t it? That’s because these things are ordinary. But maybe they’re ordinary for a reason: because they are what actually matters.CHAPTER 4: The Value of Suffering

The Self-Awareness Onion Self-awareness is like an onion. There are multiple layers to it, and the more you peel them back, the more likely you’re going to start crying at inappropriate times. Let’s say the first layer of the self-awareness onion is a simple understanding of one’s emotions. “This is when I feel happy.” “This makes me feel sad.” “This gives me hope.” Unfortunately, there are many people who suck at even this most basic level of self-awareness. I know because I’m one of them. My wife and I sometimes have a fun back-and-forth that goes something like this: HER. What’s wrong? ME. Nothing’s wrong. Nothing at all. HER. No, something’s wrong. Tell me. ME. I’m fine. Really. HER. Are you sure? You look upset. ME, with nervous laughter. Really? No, I’m okay, seriously. [Thirty minutes later . . . ] ME. . . . And that’s why I’m so fucking pissed off! He just acts as if I don’t exist half the time. We all have emotional blind spots. Often they have to do with the emotions that we were taught were inappropriate growing up. It takes years of practice and effort to get good at identifying blind spots in ourselves and then expressing the affected emotions appropriately. But this task is hugely important, and worth the effort. The second layer of the self-awareness onion is an ability to ask why we feel certain emotions. These why questions are difficult and often take months or even years to answer consistently and accurately. Most people need to go to some sort of therapist just to hear these questions asked for the first time. Such questions are important because they illuminate what we consider success or failure. Why do you feel angry? Is it because you failed to achieve some goal? Why do you feel lethargic and uninspired? Is it because you don’t think you’re good enough? This layer of questioning helps us understand the root cause of the emotions that overwhelm us. Once we understand that root cause, we can ideally do something to change it. But there’s another, even deeper level of the self-awareness onion. And that one is full of fucking tears. The third level is our personal values: Why do I consider this to be success/failure? How am I choosing to measure myself? By what standard am I judging myself and everyone around me? This level, which takes constant questioning and effort, is incredibly difficult to reach. But it’s the most important, because our values determine the nature of our problems, and the nature of our problems determines the quality of our lives. Values underlie everything we are and do. If what we value is unhelpful, if what we consider success/failure is poorly chosen, then everything based upon those values—the thoughts, the emotions, the day-to-day feelings—will all be out of whack. Everything we think and feel about a situation ultimately comes back to how valuable we perceive it to be. Most people are horrible at answering these why questions accurately, and this prevents them from achieving a deeper knowledge of their own values. Sure, they may say they value honesty and a true friend, but then they turn around and lie about you behind your back to make themselves feel better. People may perceive that they feel lonely. But when they ask themselves why they feel lonely, they tend to come up with a way to blame others—everyone else is mean, or no one is cool or smart enough to understand them—and thus they further avoid their problem instead of seeking to solve it. For many people this passes as self-awareness. And yet, if they were able to go deeper and look at their underlying values, they would see that their original analysis was based on avoiding responsibility for their own problem, rather than accurately identifying the problem. They would see that their decisions were based on chasing highs, not generating true happiness. Most self-help gurus ignore this deeper level of self-awareness as well. They take people who are miserable because they want to be rich, and then give them all sorts of advice on how to make more money, all the while ignoring important values-based questions: Why do they feel such a need to be rich in the first place? How are they choosing to measure success/failure for themselves? Is it not perhaps some particular value that’s the root cause of their unhappiness, and not the fact that they don’t drive a Bentley yet? Much of the advice out there operates at a shallow level of simply trying to make people feel good in the short term, while the real long-term problems never get solved. People’s perceptions and feelings may change, but the underlying values, and the metrics by which those values are assessed, stay the same. This is not real progress. This is just another way to achieve more highs. Honest self-questioning is difficult. It requires asking yourself simple questions that are uncomfortable to answer. In fact, in my experience, the more uncomfortable the answer, the more likely it is to be true. Take a moment and think of something that’s really bugging you. Now ask yourself why it bugs you. Chances are the answer will involve a failure of some sort. Then take that failure and ask why it seems “true” to you. What if that failure wasn’t really a failure? What if you’ve been looking at it the wrong way? A recent example from my own life: “It bugs me that my brother doesn’t return my texts or emails.” Why? “Because it feels like he doesn’t give a shit about me.” Why does this seem true? “Because if he wanted to have a relationship with me, he would take ten seconds out of his day to interact with me.” Why does his lack of relationship with you feel like a failure? “Because we’re brothers; we’re supposed to have a good relationship!” Two things are operating here: a value that I hold dear, and a metric that I use to assess progress toward that value. My value: brothers are supposed to have a good relationship with one another. My metric: being in contact by phone or email—this is how I measure my success as a brother. By holding on to this metric, I make myself feel like a failure, which occasionally ruins my Saturday mornings. We could dig even deeper, by repeating the process: Why are brothers supposed to have a good relationship? “Because they’re family, and family are supposed to be close!” Why does that seem true? “Because your family is supposed to matter to you more than anyone else!” Why does that seem true? “Because being close with your family is ‘normal’ and ‘healthy,’ and I don’t have that.” In this exchange I’m clear about my underlying value—having a good relationship with my brother—but I’m still struggling with my metric. I’ve given it another name, “closeness,” but the metric hasn’t really changed: I’m still judging myself as a brother based on frequency of contact—and comparing myself, using that metric, against other people I know. Everyone else (or so it seems) has a close relationship with their family members, and I don’t. So obviously there must be something wrong with me. But what if I’m choosing a poor metric for myself and my life? What else could be true that I’m not considering? Well, perhaps I don’t need to be close to my brother to have that good relationship that I value. Perhaps there just needs to be some mutual respect (which there is). Or maybe mutual trust is what to look for (and it’s there). Perhaps these metrics would be better assessments of brotherhood than how many text messages he and I exchange. This clearly makes sense; it feels true for me. But it still fucking hurts that my brother and I aren’t close. And there’s no positive way to spin it. There’s no secret way to glorify myself through this knowledge. Sometimes brothers—even brothers who love each other—don’t have close relationships, and that’s fine. It is hard to accept at first, but that’s fine. What is objectively true about your situation is not as important as how you come to see the situation, how you choose to measure it and value it. Problems may be inevitable, but the meaning of each problem is not. We get to control what our problems mean based on how we choose to think about them, the standard by which we choose to measure them. Shitty Values There are a handful of common values that create really poor problems for people—problems that can hardly be solved. So let’s go over some of them quickly: 1. Pleasure. Pleasure is great, but it’s a horrible value to prioritize your life around. Ask any drug addict how his pursuit of pleasure turned out. Ask an adulterer who shattered her family and lost her children whether pleasure ultimately made her happy. Ask a man who almost ate himself to death how pleasure helped him solve his problems. Pleasure is a false god. Research shows that people who focus their energy on superficial pleasures end up more anxious, more emotionally unstable, and more depressed. Pleasure is the most superficial form of life satisfaction and therefore the easiest to obtain and the easiest to lose. And yet, pleasure is what’s marketed to us, twenty-four/seven. It’s what we fixate on. It’s what we use to numb and distract ourselves. But pleasure, while necessary in life (in certain doses), isn’t, by itself, sufficient. Pleasure is not the cause of happiness; rather, it is the effect. If you get the other stuff right (the other values and metrics), then pleasure will naturally occur as a by-product. 2. Material Success. Many people measure their self-worth based on how much money they make or what kind of car they drive or whether their front lawn is greener and prettier than the next-door neighbor’s. Research shows that once one is able to provide for basic physical needs (food, shelter, and so on), the correlation between happiness and worldly success quickly approaches zero. So if you’re starving and living on the street in the middle of India, an extra ten thousand dollars a year would affect your happiness a lot. But if you’re sitting pretty in the middle class in a developed country, an extra ten thousand dollars per year won’t affect anything much—meaning that you’re killing yourself working overtime and weekends for basically nothing. The other issue with overvaluing material success is the danger of prioritizing it over other values, such as honesty, nonviolence, and compassion. When people measure themselves not by their behavior, but by the status symbols they’re able to collect, then not only are they shallow, but they’re probably assholes as well. 3. Always Being Right.Our brains are inefficient machines. We consistently make poor assumptions, misjudge probabilities, misremember facts, give in to cognitive biases, and make decisions based on our emotional whims. As humans, we’re wrong pretty much constantly, so if your metric for life success is to be right—well, you’re going to have a difficult time rationalizing all of the bullshit to yourself. The fact is, people who base their self-worth on being right about everything prevent themselves from learning from their mistakes. They lack the ability to take on new perspectives and empathize with others. They close themselves off to new and important information. It’s far more helpful to assume that you’re ignorant and don’t know a whole lot. This keeps you unattached to superstitious or poorly informed beliefs and promotes a constant state of learning and growth. 4. Staying Positive. Then there are those who measure their lives by the ability to be positive about, well, pretty much everything. Lost your job? Great! That’s an opportunity to explore your passions. Husband cheated on you with your sister? Well, at least you’re learning what you really mean to the people around you. Child dying of throat cancer? At least you don’t have to pay for college anymore! While there is something to be said for “staying on the sunny side of life,” the truth is, sometimes life sucks, and the healthiest thing you can do is admit it. Denying negative emotions leads to experiencing deeper and more prolonged negative emotions and to emotional dysfunction. Constant positivity is a form of avoidance, not a valid solution to life’s problems— problems which, by the way, if you’re choosing the right values and metrics, should be invigorating you and motivating you. It’s simple, really: things go wrong, people upset us, accidents happen. These things make us feel like shit. And that’s fine. Negative emotions are a necessary component of emotional health. To deny that negativity is to perpetuate problems rather than solve them. The trick with negative emotions is to 1) express them in a socially acceptable and healthy manner and 2) express them in a way that aligns with your values. Simple example: A value of mine is nonviolence. Therefore, when I get mad at somebody, I express that anger, but I also make a point of not punching them in the face. Radical idea, I know. But the anger is not the problem. Anger is natural. Anger is a part of life. Anger is arguably quite healthy in many situations. (Remember, emotions are just feedback.) See, it’s the punching people in the face that’s the problem. Not the anger. The anger is merely the messenger for my fist in your face. Don’t blame the messenger. Blame my fist (or your face). When we force ourselves to stay positive at all times, we deny the existence of our life’s problems. And when we deny our problems, we rob ourselves of the chance to solve them and generate happiness. Problems add a sense of meaning and importance to our life. Thus to duck our problems is to lead a meaningless (even if supposedly pleasant) existence. In the long run, completing a marathon makes us happier than eating a chocolate cake. Raising a child makes us happier than beating a video game. Starting a small business with friends while struggling to make ends meet makes us happier than buying a new computer. These activities are stressful, arduous, and often unpleasant. They also require withstanding problem after problem. Yet they are some of the most meaningful moments and joyous things we’ll ever do. They involve pain, struggle, even anger and despair—yet once they’re accomplished, we look back and get all misty-eyed telling our grandkids about them. As Freud once said, “One day, in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful.” This is why these values—pleasure, material success, always being right, staying positive—are poor ideals for a person’s life. Some of the greatest moments of one’s life are not pleasant, not successful, not known, and not positive. The point is to nail down some good values and metrics, and pleasure and success will naturally emerge as a result. These things are side effects of good values. By themselves, they are empty highs. Defining Good and Bad Values Good values are 1) reality-based, 2) socially constructive, and 3) immediate and controllable. Bad values are 1) superstitious, 2) socially destructive, and 3) not immediate or controllable. Honesty is a good value because it’s something you have complete control over, it reflects reality, and it benefits others (even if it’s sometimes unpleasant). Popularity, on the other hand, is a bad value. If that’s your value, and if your metric is being the most popular guy/girl at the dance party, much of what happens will be out of your control: you don’t know who else will be at the event, and you probably won’t know who half those people are. Second, the value/metric isn’t based on reality: you may feel popular or unpopular, when in fact you have no fucking clue what anybody else really thinks about you. (Side Note: As a rule, people who are terrified of what others think about them are actually terrified of all the shitty things they think about themselves being reflected back at them.) Some examples of good, healthy values: honesty, innovation, vulnerability, standing up for oneself, standing up for others, self-respect, curiosity, charity, humility, creativity. Some examples of bad, unhealthy values: dominance through manipulation or violence, indiscriminate fucking, feeling good all the time, always being the center of attention, not being alone, being liked by everybody, being rich for the sake of being rich, sacrificing small animals to the pagan gods. You’ll notice that good, healthy values are achieved internally. Something like creativity or humility can be experienced right now. You simply have to orient your mind in a certain way to experience it. These values are immediate and controllable and engage you with the world as it is rather than how you wish it were. Bad values are generally reliant on external events—flying in a private jet, being told you’re right all the time, owning a house in the Bahamas, eating a cannoli while getting blown by three strippers. Bad values, while sometimes fun or pleasurable, lie outside of your control and often require socially destructive or superstitious means to achieve. Values are about prioritization. Everybody would love a good cannoli or a house in the Bahamas. The question is your priorities. What are the values that you prioritize above everything else, and that therefore influence your decisionmaking more than anything else? This, in a nutshell, is what “self-improvement” is really about: prioritizing better values, choosing better things to give a fuck about. Because when you give better fucks, you get better problems. And when you get better problems, you get a better life.CHAPTER 5: You Are Always Choosing