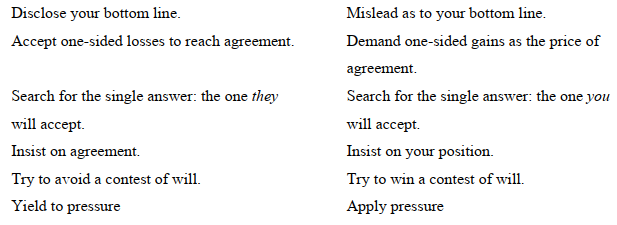

Contents: PREFACE to second edition (1991) I THE PROBLEM 1.DON'T BARGAIN OVER POSITIONS II THE METHOD 2. SEPARATE THE PEOPLE FROM THE PROBLEM 3. FOCUS ON INTERESTS, NOT POSITIONS 4. INVENT OPTIONS FOR MUTUAL GAIN 5. INSIST ON USING OBJECTIVE CRITERIA III YES, BUT 6. WHAT IF THEY ARE MORE POWERFUL? 7. WHAT IF THEY WON'T PLAY? 8. WHAT IF THEY USE DIRTY TRICKS? PREFACE In this book, we address questions about (1) the meaning and limits of "principled" negotiation (it represents practical, not moral advice); (2) dealing with someone who seems to be irrational or who has a different value system, outlook, or negotiating style; (3) practical questions, such as where to meet, who should make the first offer, and how to move from inventing options to making commitments; and (4) the role of power in negotiation. Although negotiation takes place every day, it is not easy to do well. Standard strategies for negotiation often leave people dissatisfied, worn out, or alienated — and frequently all three. People find themselves in a dilemma. They see two ways to negotiate: soft or hard. The soft negotiator wants to avoid personal conflict and so makes concessions readily in order to reach agreement. He wants an amicable resolution; yet he often ends up exploited and feeling bitter. The hard negotiator sees any situation as a contest of wills in which the side that takes the more extreme positions and holds out longer fares better. He wants to win; yet he often ends up producing an equally hard response which exhausts him and his resources and harms his relationship with the other side. Other standard negotiating strategies fall between hard and soft, but each involves an attempted trade-off between getting what you want and getting along with people. There is a third way to negotiate, a way neither hard nor soft, but rather both hard and soft. The method of principled negotiation developed at the Harvard Negotiation Project is to decide issues on their merits rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and won't do. It suggests that you look for mutual gains wherever possible, and that where your interests conflict, you should insist that the result be based on some fair standards independent of the will of either side. The method of principled negotiation is hard on the merits, soft on the people. It employs no tricks ' and no posturing. Principled negotiation shows you how to obtain what you are entitled to and still be decent. It enables you to be fair while protecting you against those who would take advantage of your fairness. Chapter 1: The Problem 1.Don't Bargain Over Positions And so it goes, on and on. Perhaps they will reach agreement; perhaps not. Arguing over positions produces unwise agreements. As more attention is paid to positions, less attention is devoted to meeting the underlying concerns of the parties. Agreement becomes less likely. Any agreement reached may reflect a mechanical splitting of the difference between final positions rather than a solution carefully crafted to meet the legitimate interests of the parties. The result is frequently an agreement less satisfactory to each side than it could have been. Arguing over positions is inefficient. The standard method of negotiation may produce either agreement, as with the price of a brass dish, or breakdown, as with the number of on-site inspections. In either event, the process takes a lot of time. Where each decision not only involves yielding to the other side but will likely produce pressure to yield further, a negotiator has little incentive to move quickly. Dragging one's feet, threatening to walk out, stonewalling, and other such tactics become commonplace. They all increase the time and costs of reaching agreement as well as the risk that no agreement will be reached at all. Arguing over positions endangers an ongoing relationship. Anger and resentment often result as one side sees itself bending to the rigid will of the other while its own legitimate concerns go unaddressed. When there are many parties, positional bargaining is even worse. If some 150 countries are negotiating, as in various United Nations conferences, positional bargaining is next to impossible. It may take all to say yes, but only one to say no. Reciprocal concessions are difficult: to whom do you make a concession? Yet even thousands of bilateral deals would still fall short of a multilateral agreement. In such situations, positional bargaining leads to the formation of coalitions among parties whose shared interests are often more symbolic than substantive. At the United Nations, such coalitions produce negotiations between "the" North and "the" South, or between "the" East and "the" West. Because there are many members in a group, it becomes more difficult to develop a common position. What is worse, once they have painfully developed and agreed upon a position, it becomes much harder to change it. Altering a position proves equally difficult when additional participants are higher authorities who, while absent from the table, must nevertheless give their approval. Being nice is no answer. There is an alternative. The answer to the question of whether to use soft positional bargaining or hard is "neither." Change the game. At the Harvard Negotiation Project we have been developing an alternative to positional bargaining: a method of negotiation explicitly designed to produce wise outcomes efficiently and amicably. This method, called principled negotiation or negotiation on the merits, can be boiled down to four basic points, These four points define a straightforward method of negotiation that can be used under almost any circumstance. Each point deals with a basic element of negotiation, and suggests what you should do about it. People: Separate the people from the problem. Interests: Focus on interests, not positions. Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do. Criteria: Insist that the result be based on some objective standard. The first point responds to the fact that human beings are not computers. We are creatures of strong emotions who often have radically different perceptions and have difficulty communicating clearly. Emotions typically become entangled with the objective merits of the problem. Taking positions just makes this worse because people's egos become identified with their positions. Hence, before working on the substantive problem, the "people problem" should be disentangled from it and dealt with separately. Figuratively if not literally, the participants should come to see themselves as working side by side, attacking the problem, not each other. Hence the first proposition: Separate the people from the problem. The second point is designed to overcome the drawback of focusing on people's stated positions when the object of a negotiation is to satisfy their underlying interests. A negotiating position often obscures what you really want. Compromising between positions is not likely to produce an agreement which will effectively take care of the human needs that led people to adopt those positions. The second basic element of the method is: Focus on interests, not positions. The third point responds to the difficulty of designing optimal solutions while under pressure. Trying to decide in the presence of an adversary narrows your vision. Having a lot at stake inhibits creativity. So does searching for the one right solution. You can offset these constraints by setting aside a designated time within which to think up a wide range of possible solutions that advance shared interests and creatively reconcile differing interests. Hence the third basic point: Before trying to reach agreement, invent options for mutual gain. Where interests are directly opposed, a negotiator may be able to obtain a favorable result simply by being stubborn. That method tends to reward intransigence and produce arbitrary results. However, you can counter such a negotiator by insisting that his single say-so is not enough and that the agreement must reflect some fair standard independent of the naked will of either side. This does not mean insisting that the terms be based on the standard you select, but only that some fair standard such as market value, expert opinion, custom, or law determine the outcome. By discussing such criteria rather than what the parties are willing or unwilling to do, neither party need give in to the other; both can defer to a fair solution. Hence the fourth basic point: Insist on using objective criteria. During the planning stage you deal with the same four elements a second time, both generating ideas and deciding what to do. How do you propose to handle the people problems? Of your interests, which are most important? And what are some realistic objectives? You will want to generate additional options and additional criteria for deciding among them. Again during the discussion stage, when the parties communicate back and forth, looking toward agreement, the same four elements are the best subjects to discuss. Differences in perception, feelings of frustration and anger, and difficulties in communication can be acknowledged and addressed. Each side should come to understand the interests of the other. Both can then jointly generate options that are mutually advantageous and seek agreement on objective standards for resolving opposed interests. To sum up, in contrast to positional bargaining, the principled negotiation method of focusing on basic interests, mutually satisfying options, and fair standards typically results in a wise agreement. The method permits you to reach a gradual consensus on a joint decision efficiently without all the transactional costs of digging in to positions only to have to dig yourself out of them. And separating the people from the problem allows you to deal directly and empathetically with the other negotiator as a human being, thus making possible an amicable agreement. CHAPTER 2: SEPARATE THE PEOPLE FROM THE PROBLEM Negotiators are people first A basic fact about negotiation, easy to forget in corporate and international transactions, is that you are dealing not with abstract representatives of the "other side," but with human beings. They have emotions, deeply held values, and different backgrounds and viewpoints; and they are unpredictable. So are you. This human aspect of negotiation can be either helpful or disastrous. The process of working out an agreement may produce a psychological commitment to a mutually satisfactory outcome. A working relationship where trust, understanding, respect, and friendship are built up over time can make each new negotiation smoother and more efficient. And people's desire to feel good about themselves, and their concern for what others will think of them, can often make them more sensitive to another negotiator's interests. On the other hand, people get angry, depressed, fearful, hostile, frustrated, and offended. They have egos that are easily threatened. They see the world from their own personal vantage point, and they frequently confuse their perceptions with reality. Routinely, they fail to interpret what you say in the way you intend and do not mean what you understand them to say. Misunderstanding can reinforce prejudice and lead to reactions that produce counterreactions in a vicious circle; rational exploration of possible solutions becomes impossible and a negotiation fails. The purpose of the game becomes scoring points, confirming negative impressions, and apportioning blame at the expense of the substantive interests of both parties. Failing to deal with others sensitively as human beings prone to human reactions can be disastrous for a negotiation. Whatever else you are doing at any point during a negotiation, from preparation to follow-up, it is worth asking yourself, "Am I paying enough attention to the people problem?" Every negotiator has two kinds of interests: in the substance and in the relationship The relationship tends to become entangled with the problem. Positional bargaining puts relationship and substance in conflict. Framing a negotiation as a contest of will over positions aggravates the entangling process. Separate the relationship from the substance; deal directly with the people problem. Dealing with a substantive problem and maintaining a good working relationship need not be conflicting goals if the parties are committed and psychologically prepared to treat each separately on its own legitimate merits. Base the relationship on accurate perceptions, clear communication, appropriate emotions, and a forward-looking, purposive outlook. Deal with people problems directly; don't try to solve them with substantive concessions. To deal with psychological problems, use psychological techniques. Where perceptions are inaccurate, you can look for ways to educate. If emotions run high, you can find ways for each person involved to let off steam. Where misunderstanding exists, you can work to improve communication. To find your way through the jungle of people problems, it is useful to think in terms of three basic categories: perception, emotion, and communication. The various people problems all fall into one of these three baskets. In negotiating it is easy to forget that you must deal not only with their people problems, but also with your own. Your anger and frustration may obstruct an agreement beneficial to you. Your perceptions are likely to be one-sided, and you may not be listening or communicating adequately. The techniques which follow apply equally well to your people problems as to those of the other side. Perception 1. Put yourself in their shoes. - Understanding their point of view is not the same as agreeing with it. - Don't deduce their intentions from your fears. People tend to assume that whatever they fear, the other side intends to do. - It is all too easy to fall into the habit of putting the worst interpretation on what the other side says or does. A suspicious interpretation often follows naturally from one's existing perceptions. - Don't blame them for your problem. But even if blaming is justified, it is usually counterproductive. Under attack, the other side will become defensive and will resist what you have to say. They will cease to listen, or they will strike back with an attack of their own. Assessing blame firmly entangles the people with the problem. - When you talk about the problem, separate the symptoms from the person with whom you are talking. Consider this: "Your company is totally unreliable. Every time you service our rotary generator here at the factory, you do a lousy job and it breaks down again." Versus this: "Our rotary generator that you service has broken down again. That is three times in the last month. The first time it was out of order for an entire week. This factory needs a functioning generator. I want your advice on how we can minimize our risk of generator breakdown. Should we change service companies, sue the manufacturer, or what?" 2. Discuss each other's perceptions. 3. Look for opportunities to act inconsistently with their perceptions. 4. Give them a stake in the outcome by making sure they participate in the process. 5. Face-saving: Make your proposals consistent with their values. Face-saving involves reconciling an agreement with principle and with the self-image of the negotiators. Its importance should not be underestimated. Emotion 1. First recognize and understand emotions, theirs and yours. 2. Make emotions explicit and acknowledge them as legitimate. 3. Allow the other side to let off steam. 4. Don't react to emotional outbursts. 5. Use symbolic gestures. Any lover knows that to end a quarrel the simple gesture of bringing a red rose goes a long way. Communication There are three big problems in communication. First, negotiators may not be talking to each other, or at least not in such a way as to be understood. Second, even if you are talking directly and clearly to them, they may not be hearing you. The third communication problem is misunderstanding. What one says, the other may misinterpret. Solutions: 1. The third communication problem is misunderstanding. What one says, the other may misinterpret. 2. Speak to be understood. 3. Speak about yourself, not about them. In many negotiations, each side explains and condemns at great length the motivations and intentions of the other side. It is more persuasive, however, to describe a problem in terms of its impact on you than in terms of what they did or why: "I feel let down" instead of "You broke your word." "We feel discriminated against" rather than "You're a racist." If you make a statement about them that they believe is untrue, they will ignore you or get angry; they will not focus on your concern. But a statement about how you feel is difficult to challenge. You convey the same information without provoking a defensive reaction that will prevent them from taking it in. 4. Speak for a purpose. PREVENTION WORKS BEST The techniques just described for dealing with problems of perception, emotion, and communication usually work well. However, the best time for handling people problems is before they become people problems. Build a working relationship. Face the problem, not the people. Like two shipwrecked sailors in a lifeboat at sea quarreling over limited rations and supplies, negotiators may begin by seeing each other as adversaries. Each may view the other as a hindrance. To survive, however, those two sailors will want to disentangle the objective problems from the people. They will want to identify the needs of each, whether for shade, medicine, water, or food. They will want to go further and treat the meeting of those needs as a shared problem, along with other shared problems like keeping watch, catching rainwater, and getting the lifeboat to shore. Seeing themselves as engaged in side-by-side efforts to solve a mutual problem, the sailors will become better able to reconcile their conflicting interests as well as to advance their shared interests. Similarly with two negotiators. However difficult personal relations may be between us, you and I become better able to reach an amicable reconciliation of our various interests when we accept that task as a shared problem and face it jointly. CHAPTER 3. FOCUS ON INTERESTS, NOT POSITIONS Consider the story of two men quarreling in a library. One wants the window open and the other wants it closed. They bicker back and forth about how much to leave it open: a crack, halfway, three quarters of the way. No solution satisfies them both. Enter the librarian. She asks one why he wants the window open: "To get some fresh air." She asks the other why he wants it closed: "To avoid the draft." After thinking a minute, she opens wide a window in the next room, bringing in fresh air without a draft. 1. For a wise solution reconcile interests, not positions Interests define the problem. The basic problem in a negotiation lies not in conflicting positions, but in the conflict between each side's needs, desires, concerns, and fears. Reconciling interests rather than positions works for two reasons. First, for every interest there usually exist several possible positions that could satisfy it. All too often people simply adopt the most obvious position. When you do look behind opposed positions for the motivating interests, you can often find an alternative position which meets not only your interests but theirs as well. Reconciling interests rather than compromising between positions also works because behind opposed positions lie many more interests than conflicting ones. 2. Behind opposed positions lie shared and compatible interests, as well as conflicting ones. For example, look at the interests a tenant shares with a prospective landlord: 1. Both want stability. The landlord wants a stable tenant; the tenant wants a permanent address. 2. Both would like to see the apartment well maintained. The tenant is going to live there; the landlord wants to increase the value of the apartment as well as the reputation of the building. 3. Both are interested in a good relationship with each other. The landlord wants a tenant who pays the rent regularly; the tenant wants a responsive landlord who will carry out the necessary repairs. They may have interests that do not conflict but simply differ. For example: 1. The tenant may not want to deal with fresh paint, to which he is allergic. The landlord will not want to pay the costs of repainting all the other apartments. 2. The landlord would like the security of a down payment of the first month's rent, and he may want it by tomorrow. The tenant, knowing that this is a good apartment, may be indifferent on the question of paying tomorrow or later. How do you identify interests? Ask "Why?" One basic technique is to put yourself in their shoes. Ask "Why not?" Think about their choice. Consider, for example, the negotiations between the United States and Iran in 1980 over the release of the fifty-two U.S. diplomats and embassy personnel held hostage in Tehran by student militants. While there were a host of serious obstacles to a resolution of this dispute, the problem is illuminated simply by looking at the choice of a typical student leader. The demand of the United States was clear: "Release the hostages." During much of 1980 each student leader's choice must have looked something like that illustrated by the balance sheet below: Realize that each side has multiple interests. In almost every negotiation each side will have many interests, not just one. As a tenant negotiating a lease, for example, you may want to obtain a favorable rental agreement, to reach it quickly with little effort, and to maintain a good working relationship with your landlord. You will have not only a strong interest in affecting any agreement you reach, but also one in effecting an agreement. You will be simultaneously pursuing both your independent and your shared interests. The most powerful interests are basic human needs. Basic human needs include: • security • economic well-being • a sense of belonging • recognition • control over one's life Make a list. To sort out the various interests of each side, it helps to write them down as they occur to you. This will not only help you remember them; it will also enable you to improve the quality of your assessment as you learn new information and to place interests in their estimated order of importance. Talking about interests. The purpose of negotiating is to serve your interests. The chance of that happening increases when you communicate them. The other side may not know what your interests are, and you may not know theirs. One or both of you may be focusing on past grievances instead of on future concerns. Or you may not even be listening to each other. How do you discuss interests constructively without getting locked into rigid positions? Make your interests come alive. If you go with a raging ulcer to see a doctor, you should not hope for much relief if you describe it as a mild stomachache. It is your job to have the other side understand exactly how important and legitimate your interests are. One guideline is be specific. Concrete details not only make your description credible, they add impact. Acknowledge their interests as part of the problem. Each of us tends to be so concerned with his or her own interests that we pay too little heed to the interests of others. People listen better if they feel that you have understood them. They tend to think that those who understand them are intelligent and sympathetic people whose own opinions may be worth listening to. So if you want the other side to appreciate your interests, begin by demonstrating that you appreciate theirs. Put the problem before your answer. In talking to someone who represents a construction company, you might say, "We believe you should build a fence around the project within forty-eight hours and beginning immediately should restrict the speed of your trucks on Oak Street to fifteen miles an hour. Now let me tell you why...." If you do, you can be quite certain that he will not be listening to the reasons. He has heard your position and is no doubt busy preparing arguments against it. He was probably disturbed by your tone or by the suggestion itself. As a result, your justification will slip by him altogether. If you want someone to listen and understand your reasoning, give your interests and reasoning first and your conclusions or proposals later. Tell the company first about the dangers they are creating for young children and about your sleepless nights. Then they will be listening carefully, if only to try to figure out where you will end up on this question. And when you tell them, they will understand why. Look forward, not back. It is surprising how often we simply react to what someone else has said or done. Two people will often fall into a pattern of discourse that resembles a negotiation, but really has no such purpose whatsoever. They disagree with each other over some issue, and the talk goes back and forth as though they were seeking agreement. In fact, the argument is being carried on as a ritual, or simply a pastime. Each is engaged in scoring points against the other or in gathering evidence to confirm views about the other that have long been held and are not about to be changed. Neither party is seeking agreement or is even trying to influence the other. If you ask two people why they are arguing, the answer will typically identify a cause, not a purpose. You will satisfy your interests better if you talk about where you would like to go rather than about where you have come from. Instead of arguing with the other side about the past — about last quarter's costs (which were too high), last week's action (taken without adequate authority), or yesterday's performance (which was less than expected) — talk about what you want to have happen in the future. Instead of asking them to justify what they did yesterday, ask, "Who should do what tomorrow?" Be concrete but flexible. In a negotiation you want to know where you are going and yet be open to fresh ideas. To avoid having to make a difficult decision on what to settle for, people will often go into a negotiation with no other plan than to sit down with the other side and see what they offer or demand. Be hard on the problem, soft on the people. One useful rule of thumb is to give positive support to the human beings on the other side equal in strength to the vigor with which you emphasize the problem. This combination of support and attack may seem inconsistent. Psychologically, it is; the inconsistency helps make it work. A well-known theory of psychology, the theory of cognitive dissonance, holds that people dislike inconsistency and will act to eliminate it. By attacking a problem, such as speeding trucks on a neighborhood street, and at the same time giving the company representative positive support, you create cognitive dissonance for him. To overcome this dissonance, he will be tempted to dissociate himself from the problem in order to join you in doing something about it. CHAPTER 4. INVENT OPTIONS FOR MUTUAL GAIN In most negotiations there are four major obstacles that inhibit the inventing of an abundance of options: (1) premature judgment; (2) searching for the single answer; (3) the assumption of a fixed pie; and (4) thinking that "solving their problem is their problem." (1) Premature judgment Inventing options does not come naturally. Not inventing is the normal state of affairs, even when you are outside a stressful negotiation. If you were asked to name the one person in the world most deserving of the Nobel Peace Prize, any answer you might start to propose would immediately encounter your reservations and doubts. How could you be sure that that person was the most deserving? Your mind might well go blank, or you might throw out a few answers that would reflect conventional thinking: "Well, maybe the Pope, or the President." Nothing is so harmful to inventing as a critical sense waiting to pounce on the drawbacks of any new idea. Judgment hinders imagination. Under the pressure of a forthcoming negotiation, your critical sense is likely to be sharper. You would think, "practical negotiation appears to call for practical thinking, not wild ideas". (2) Searching for the single answer In most people's minds, inventing simply is not part of the negotiating process. People see their job as narrowing the gap between positions, not broadening the options available. They tend to think, "We're having a hard enough time agreeing as it is. The last thing we need is a bunch of different ideas." Since the end product of negotiation is a single decision, they fear that freefloating discussion will only delay and confuse the process. If the first impediment to creative thinking is premature criticism, the second is premature closure. By looking from the outset for the single best answer, you are likely to short-circuit a wiser decision-making process in which you select from a large number of possible answers. (3) The assumption of a fixed pie A third explanation for why there may be so few good options on the table is that each side sees the situation as essentially either/or — either I get what is in dispute or you do. A negotiation often appears to be a "fixed-sum" game; $100 more for you on the price of a car means $100 less for me. Why bother to invent if all the options are obvious and I can satisfy you only at my own expense? (4) Thinking that "solving their problem is their problem" For a negotiator to reach an agreement that meets his own self-interest he needs to develop a solution, which also appeals to the self-interest of the other. There also frequently exists a psychological reluctance to accord any legitimacy to the views of the other side; it seems disloyal to think up ways to satisfy them. Shortsighted self-concern thus leads a negotiator to develop only partisan positions, partisan arguments, and one-sided solutions. PRESCRIPTION To invent creative options, then, you will need (1) to separate the act of inventing options from the act of judging them; (2) to broaden the options on the table rather than look for a single answer; (3) to search for mutual gains; and (4) to invent ways of making their decisions easy. Each of these steps is discussed below. 1. Separate inventing from deciding A brainstorming session is designed to produce as many ideas as possible to solve the problem at hand. The key ground rule is to postpone all criticism and evaluation of ideas. The group simply invents ideas without pausing to consider whether they are good or bad, realistic or unrealistic. With those inhibitions removed, one idea should stimulate another, like firecrackers setting off one another. Below are some brainstorming guidelines: Before brainstorming: 1. Define your purpose. Think of what you would like to walk out of the meeting with. 2. Choose a few participants. The group should normally be large enough to provide a stimulating interchange, yet small enough to encourage both individual participation and freewheeling inventing — usually between five and eight people. 3. Change the environment. Select a time and place distinguishing the session as much as possible from regular discussions. The more different a brainstorming session seems from a normal meeting, the easier it is for participants to suspend judgment. 4. Design an informal atmosphere. What does it take for you and others to relax? It may be talking over a drink, or meeting at a vacation lodge in some picturesque spot, or simply taking off your tie and jacket during the meeting and calling each other by your first names. 5. Choose a facilitator. Someone at the meeting needs to facilitate — to keep the meeting on track, to make sure everyone gets a chance to speak, to enforce any ground rules, and to stimulate discussion by asking questions. Daring brainstorming: 1. Seat the participants side by facing the problem. The physical reinforces the psychological. Physically sitting side by side can reinforce the mental attitude of tackling a common problem together. People facing each other tend to respond personally and engage in dialogue or argument; people sitting side by side in a semicircle of chairs facing a blackboard tend to respond to the problem depicted there. 2. Clarify the ground rules, including the no-criticism rule. If the participants do not all know each other, the meeting begins with introductions all around, followed by clarification of the ground rules. Outlaw negative criticism of any kind. 3. Brainstorm. Once the purpose of the meeting is clear, let your imaginations go. Try to come up with a long list of ideas, approaching the question from every conceivable angle. 4. Record the ideas in full view. Recording ideas either on a blackboard or, better, on large sheets of newsprint gives the group a tangible sense of collective achievement; it reinforces the no-criticism rule; it reduces the tendency to repeat; and it helps stimulate other ideas. After brainstorming: 1. Star the most promising ideas. After brainstorming, relax the no-criticism rule in order to winnow out the most promising ideas. You are still not at the stage of deciding; you are merely nominating ideas worth developing further. Mark those ideas that members of the group think are best. 2. Invent improvements for promising ideas. Take one promising idea and invent ways to make it better and more realistic, as well as ways to carry it out. The task at this stage is to make the idea as attractive as you can. Preface constructive criticism with: "What I like best about that idea is.... Might it be better if... ?" 3. Set up a time to evaluate ideas and decide. Before you break up, draw up a selective and improved list of ideas from the session and set up a time for deciding which of these ideas to advance in your negotiation and how. Consider brainstorming with the other side. (2) Broaden your options Even with the best of intentions, participants in a brainstorming session are likely to operate on the assumption that they are really looking for the one best answer, trying to find a needle in a haystack by picking up every blade of hay. At this stage in a negotiation, however, you should not be looking for the right path. You are developing room within which to negotiate. Room can be made only by having a substantial number of markedly different ideas — ideas on which you and the other side can build later in the negotiation, and among which you can then jointly choose. CIRCLE CHART The Four Basic Steps in Inventing Options Look through the eyes of different experts. Invent agreements of different strengths. The pairs of adjectives below suggest potential agreements of differing "strengths": STRONGER --- WEAKER Substantive --- Procedural Permanent --- Provisional Comprehensive --- Partial Final --- In principle Unconditional --- Contingent Binding --- Nonbinding First-order --- Second-order Change the scope of a proposed agreement. Consider the possibility of varying not only the strength of the agreement but also its scope. You could, for instance, "fractionate" your problem into smaller and perhaps more manageable units. It is also provocative to ask how the subject matter might be enlarged so as to "sweeten the pot" and make agreement more attractive. The dispute between India and Pakistan over the waters of the Indus River became more amenable to settlement when the World Bank entered the discussions; the parties were challenged to invent new irrigation projects, new storage dams, and other engineering works for the benefit of both nations, all to be funded with the assistance of the Bank. Look for mutual gain Identify shared interests. As a negotiator, you will almost always want to look for solutions that will leave the other side satisfied as well. If the customer feels cheated in a purchase, the store owner has also failed; he may lose a customer and his reputation may suffer. An outcome in which the other side gets absolutely nothing is worse for you than one which leaves them mollified. Three points about shared interests are worth remembering. First, shared interests lie latent in every negotiation. They may not be immediately obvious. Ask yourself: Do we have a shared interest in preserving our relationship? What opportunities lie ahead for cooperation and mutual benefit? What costs would we bear if negotiations broke off? Are there common principles, like a fair price, that we both can respect? Second, shared interests are opportunities, not godsends. To be of use, you need to make something out of them. It helps to make a shared interest explicit and to formulate it as a shared goal. In other words, make it concrete and future oriented. Third, stressing your shared interests can make the negotiation smoother and more amicable. Passengers in a lifeboat afloat in the middle of the ocean with limited rations will subordinate their differences over food in pursuit of their shared interest in getting to shore. Dovetail differing interests. Consider once again the two sisters quarreling over an orange. Each sister wanted the orange, so they split it, failing to realize that one wanted only the fruit to eat and the other only the peel for baking. In this case as in many others, a satisfactory agreement is made possible because each side wants different things. This is genuinely startling if you think about it. People generally assume that differences between two parties create the problem. Yet differences can also lead to a solution. Agreement is often based on disagreement. It is as absurd to think, for example, that you should always begin by reaching agreement on the facts as it is for a buyer of stock to try to convince the seller that the stock is likely to go up. If they did agree that the stock would go up, the seller would probably not sell. What makes a deal likely is that the buyer believes the price will go up and the seller believes it will go down. The difference in belief provides the basis for a deal. Many creative agreements reflect this principle of reaching agreement through differences. Differences in interests and belief make it possible for an item to be high benefit to you, yet low cost to the other side. Consider the nursery rhyme: Jack Sprat could eat no fat His wife could eat no lean, And so betwixt them both They licked the platter clean. The kinds of differences that best lend themselves to dovetailing are differences in interests, in beliefs, in the value placed on time, in forecasts, and in aversion to risk. Any difference in interests? The following brief checklist suggests common variations in interest to look for: ONE PARTY CARES MORE ABOUT --- THE OTHER PARTY CARES MORE ABOUT form --- substance economic considerations --- political considerations internal considerations --- external considerations symbolic considerations --- practical considerations immediate future --- more distant future ad hoc results --- the relationship hardware --- ideology progress --- respect for tradition precedent --- this case prestige, reputation --- results political points --- group welfare Different beliefs? If I believe I'm right, and you believe you're right, we can take advantage of this difference in beliefs. We may both agree to have an impartial arbitrator settle the issue, each confident of victory. If two factions of the union leadership cannot agree on a certain wage proposal, they can agree to submit the issue to a membership vote. Different values placed on time? You may care more about the present while the other side cares more about the future. In the language of business, you discount future value at different rates. An installment plan works on this principle. The buyer is willing to pay a higher price for the car if he can pay later; the seller is willing to accept payment later if he gets a higher price. Different forecasts? In a salary negotiation between an aging baseball star and a major league baseball team, the player may expect to win a lot of games while the team owner has the opposite expectation. Taking advantage of these different expectations, they can both agree on a base salary of $100,000 plus $50,000 if the player pitches so well that on the average he permits less than three earned runs per game. Differences in aversion to risk? One last kind of difference which you may capitalize on is aversion to risk. Take, for example, the issue of deep-seabed mining in the Law of the Sea negotiations. How much should the mining companies pay the international community for the privilege of mining? The mining companies care more about avoiding big losses than they do about making big gains. For them deep-seabed mining is a major investment. They want to reduce the risk. The international community, on the other hand, is concerned with revenue. If some company is going to make a lot of money out of "the common heritage of mankind," the rest of the world wants a generous share. In this difference lies the potential for a bargain advantageous to both sides. Risk can be traded for revenue. Exploiting this difference in aversion to risk, the proposed treaty provides for charging the companies low rates until they recover their investment — in other words, while their risk is high — and much higher rates thereafter, when their risk is low. Ask for their preferences. If dovetailing had to be summed up in one sentence, it would be: Look for items that are of low cost to you and high benefit to them, and vice versa. Differences in interests, priorities, beliefs, forecasts, and attitudes toward risk all make dovetailing possible. A negotiator's motto could be "Vive la difference! Make their decision easy Whose shoes? Are you trying to influence a single negotiator, an absent boss, or some committee or other collective decision-making body? You cannot negotiate successfully with an abstraction like "Houston" or "the University of California." Instead of trying to persuade "the insurance company" to make a decision, it is wiser to focus your efforts on getting one claims agent to make a recommendation. However complex the other side's decisional process may seem, you will understand it better if you pick one person — probably the person with whom you are dealing — and see how the problem looks from his or her point of view. By focusing on one person you are not ignoring complexities. Rather, you are handling them by understanding how they impinge on the person with whom you are negotiating. You may come to appreciate your negotiating role in a new light, and see your job, for example, as strengthening that person's hand or giving her arguments that she will need to persuade others to go along. One British ambassador described his job as "helping my opposite number get new instructions." If you place yourself firmly in the shoes of your opposite number, you will understand his problem and what kind of options might solve it. What decision? # Frequently you want as much as you can get, but you yourself do not know how much that is. You are likely to say, in effect, "Come up with something and I will tell you if it is enough." That may seem reasonable to you, but when you look at it from the other's point of view, you will understand the need to invent a more appealing request. For whatever they do or say, you are likely to consider that merely a floor — and ask for more. Requesting the other side to be "more forthcoming" will probably not produce a decision you want. # Many negotiators are uncertain whether they are asking for words or for performance. Yet the distinction is critical. If it is performance you want, do not add something for "negotiating room." If you want a horse to jump a fence, don't raise the fence. If you want to sell a soft drink from a vending machine for thirty-five cents, don't mark the price at fifty cents to give yourself room to negotiate. # Most of the time you will want a promise — an agreement. Take pencil and paper in hand and try drafting a few possible agreements. It is never too early in a negotiation to start drafting as an aid to clear thinking. Prepare multiple versions, starting with the simplest possible. What are some terms that the other party could sign, terms that would be attractive to them as well as to you? Can you reduce the number of people whose approval would be required? Can you formulate an agreement that will be easy for them to implement? The other side will take into account difficulties in carrying out an agreement; you should too. # Frequently you want as much as you can get, but you yourself do not know how much that is. You are likely to say, in effect, "Come up with something and I will tell you if it is enough." That may seem reasonable to you, but when you look at it from the other's point of view, you will understand the need to invent a more appealing request. For whatever they do or say, you are likely to consider that merely a floor — and ask for more. Requesting the other side to be "more forthcoming" will probably not produce a decision you want. Making threats is not enough. In addition to the content of the decision you would like them to make, you will want to consider from their point of view the consequences of following that decision. If you were they, what results would you most fear? What would you hope for? We often try to influence others by threats and warnings of what will happen if they do not decide as we would like. Offers are usually more effective. Concentrate both on making them aware of the consequences they can expect if they do decide as you wish and on improving those consequences from their point of view. How can you make your offers more credible? What are some specific things that they might like? Would they like to be given credit for having made the final proposal? Would they like to make the announcement? What can you invent that might be attractive to them but low in cost to yourself? To evaluate an option from the other side's point of view, consider how they might be criticized if they adopted it. Write out a sentence or two illustrating what the other side's most powerful critic might say about the decision you are thinking of asking for. Then write out a couple of sentences with which the other side might reply in defense. Such an exercise will help you appreciate the restraints within which the other side is negotiating. It should help you generate options that will adequately meet their interests so that they can make a decision that meets yours. A final test of an option is to write it out in the form of a "yesable proposition." Try to draft a proposal to which their responding with the single word "yes" would be sufficient, realistic, and operational. When you can do so, you have reduced the risk that your immediate self-interest has blinded you to the necessity of meeting concerns of the other side. In a complex situation, creative inventing is an absolute necessity. In any negotiation it may open doors and produce a range of potential agreements satisfactory to each side. Therefore, generate many options before selecting among them. Invent first; decide later. Look for shared interests and differing interests to dovetail. And seek to make their decision easy. CHAPTER 5. INSIST ON USING OBJECTIVE CRITERIA Deciding on the basis of will is costly As discussed in Chapter 1, trying to reconcile differences on the basis of will has serious costs. No negotiation is likely to be efficient or amicable if you pit your will against theirs, and either you have to back down or they do. And whether you are choosing a place to eat, organizing a business, or negotiating custody of a child, you are unlikely to reach a wise agreement as judged by any objective standard if you take no such standard into account. If trying to settle differences of interest on the basis of will has such high costs, the solution is to negotiate on some basis independent of the will of either side — that is, on the basis of objective criteria. The case for using objective criteria The approach to negotiation is to commit yourself to reaching a solution based on principle, not pressure. Concentrate on the merits of the problem, not the mettle of the parties. Be open to reason, but closed to threats. Principled negotiation produces wise agreements amicably and efficiently. - A constant battle for dominance threatens a relationship; principled negotiation protects it. - Рeople using objective criteria tend to use time more efficiently talking about possible standards and solutions. Developing objective criteria 1. Fair standards. Depending on the issue, you may wish to propose that an agreement be based upon: market value precedent scientific judgment professional standards efficiency costs what a court would decide moral standards equal treatment tradition reciprocity, and etc. 2. Fair procedures. To produce an outcome independent of will, you can use either fair standards for the substantive question or fair procedures for resolving the conflicting interests. Consider, for example, the age-old way to divide a piece of cake between two children: one cuts and the other chooses. Neither can complain about an unfair division. Negotiating with objective criteria Having identified some objective criteria and procedures, how do you go about discussing them with the other side? There are three basic points to remember: 1. Frame each issue as a joint search for objective criteria. 2. Reason and be open to reason as to which standards are most appropriate and how they should be applied. 3. Never yield to pressure, only to principle. In short, focus on objective criteria firmly but flexibly. 1. Frame each issue as a joint search for objective criteria. - Ask "What's your theory?" If the seller starts by giving you a position, such as "The price is $55,000," ask for the theory behind that price: "How did you arrive at that figure?" Treat the problem as though the seller too is looking for a fair price based on objective criteria. - Agree first on principles. Before even considering possible terms, you may want to agree on the standard or standards to apply 2. Reason and be open to reason. If after a thorough discussion of the merits of an issue you still cannot accept their proposed criteria as the most appropriate, you might suggest putting them to a test. Agree on someone you both regard as fair and give him or her a list of the proposed criteria. Ask the person to decide which are the fairest or most appropriate for your situation. Since objective criteria are supposed to be legitimate and because legitimacy implies acceptance by a great many people, this is a fair thing to ask. You are not asking the third party to settle your substantive dispute — just to give you advice on what standard to use in settling it. The difference between seeking agreement on the appropriate principles for deciding a matter and using principles simply as arguments to support positions is sometimes subtle, but always significant. A principled negotiator is open to reasoned persuasion on the merits; a positional bargainer is not. It is the combination of openness to reason with insistence on a solution based on objective criteria that makes principled negotiation so persuasive and so effective at getting the other side to play. 3. Never yield to pressure. Pressure can take many forms: a bribe, a threat, a manipulative appeal to trust, or a simple refusal to budge. In all these cases, the principled response is the same: invite them to state their reasoning, suggest objective criteria you think apply, and refuse to budge except on this basis. Never yield to pressure, only to principle. Case study: “It's company policy” Let's look at a real case where one party used positional bargaining and the other principled negotiation. Tom, one of our colleagues, had his parked car totally destroyed by a dump truck. The car was covered by insurance, but the exact amount Tom could recover remained for him to work out with the insurance adjuster. CHAPTER 6. WHAT IF THEY ARE MORE POWERFUL? Develop Your BATNA — Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement In response to power, the most any method of negotiation can do is to meet two objectives: first, to protect you against making an agreement you should reject and second, to help you make the most of the assets you do have so that any agreement you reach will satisfy your interests as well as possible. Let's take each objective in turn. Protecting yourself When you are trying to catch an airplane your goal may seem tremendously important; looking back on it, you see you could have caught the next plane. Negotiation will often present you with a similar situation. You will worry, for instance, about failing to reach agreement on an important business deal in which you have invested a great deal of yourself. Under these conditions, a major danger is that you will be too accommodating to the views of the other side — too quick to go along. The siren song of "Let's all agree and put an end to this" becomes persuasive. You may end up with a deal you should have rejected. The cost of using a bottom line. Having a bottom line makes it easier to resist pressure and temptations of the moment. Your predetermined bottom line may save you from making a decision you later regret. But the protection afforded by adopting a bottom line involves high costs. It limits your ability to benefit from what you learn during negotiation. By definition, a bottom line is a position that is not to be changed. To that extent you have shut your ears, deciding in advance that nothing the other party says could cause you to raise or lower that bottom line. A bottom line also inhibits imagination. It reduces the incentive to invent a tailor-made solution which would reconcile differing interests in a way more advantageous for both you and them. Almost every negotiation involves more than one variable. A bottom line — by its very nature rigid — is almost certain to be too rigid. Know your BATNA. The reason you negotiate is to produce something better than the results you can obtain without negotiating. What are those results? What is that alternative? What is your BATNA — your Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement? That is the standard against which any proposed agreement should be measured. That is the only standard which can protect you both from accepting terms that are too unfavorable and from rejecting terms it would be in your interest to accept. Your BATNA not only is a better measure but also has the advantage of being flexible enough to permit the exploration of imaginative solutions. Instead of ruling out any solution which does not meet your bottom line, you can compare a proposal with your BATNA to see whether it better satisfies your interests. The insecurity of an unknown BATNA. As valuable as knowing your BATNA may be, you may hesitate to explore alternatives. You hope this buyer or the next will make you an attractive offer for the house. You may avoid facing the question of what you will do if no agreement is reached. You may think to yourself, "Let's negotiate first and see what happens. If things don't work out, then I'll figure out what to do." But having at least a tentative answer to the question is absolutely essential if you are to conduct your negotiations wisely. Whether you should or should not agree on something in a negotiation depends entirely upon the attractiveness to you of the best available alternative. Formulate a trip wire. Although your BATNA is the true measure by which you should judge any proposed agreement, you may want another test as well. In order to give you early warning that the content of a possible agreement is beginning to run the risk of being too unattractive, it is useful to identify one far from perfect agreement that is better than your BATNA. Before accepting any agreement worse than this trip-wire package, you should take a break and reexamine the situation. Like a bottom line, a trip wire can limit the authority of an agent. "Don't sell for less than $158,000, the price I paid plus interest, until you've talked to me." A trip wire should provide you with some margin in reserve. If after reaching the standard reflected in your trip wire you decide to call in a mediator, you have left him with something on your side to work with. You still have some room to move. Making the most of your assets The better your BATNA, the greater your power. Develop your BATNA. Generating possible BATNAs requires three distinct operations: (1) inventing a list of actions you might conceivably take if no agreement is reached; (2) improving some of the more promising ideas and converting them into practical alternatives; and (3) selecting, tentatively, the one option that seems best. Consider the other side's BATNA You should also think about the alternatives to a negotiated agreement available to the other side. They may be unduly optimistic about what they can do if no agreement is reached. Perhaps they have a vague notion that they have a great many options and are under the influence of their cumulative total. The more you can learn of their options, the better prepared you are for negotiation. Knowing their alternatives, you can realistically estimate what you can expect from the negotiation. If they appear to overestimate their BATNA, you will want to lower their expectations. Their BATNA may be better for them than any fair solution you can imagine. If both sides have attractive BATNAs, the best outcome of the negotiation — for both parties — may well be not to reach agreement. In such cases a successful negotiation is one in which you and they amicably and efficiently discover that the best way to advance your respective interests is for each of you to look elsewhere and not to try further to reach agreement. When the other side is powerful If the other side has big guns, you do not want to turn a negotiation into a gunfight. The stronger they appear in terms of physical or economic power, the more you benefit by negotiating on the merits. To the extent that they have muscle and you have principle, the larger a role you can establish for principle the better off you are. Having a good BATNA can help you negotiate on the merits. You can convert such resources as you have into effective negotiating power by developing and improving your BATNA. Apply knowledge, time, money, people, connections, and wits into devising the best solution for you independent of the other side's assent. The more easily and happily you can walk away from a negotiation, the greater your capacity to affect its outcome. Developing your BATNA thus not only enables you to determine what is a minimally acceptable agreement, it will probably raise that minimum. Developing your BATNA is perhaps the most effective course of action you can take in dealing with a seemingly more powerful negotiator. CHAPTER 7. WHAT IF THEY WON'T PLAY? Use Negotiation Jujitsu Talking about interests, options, and standards may be a wise, efficient, and amicable game, but what if the other side won't play? While you try to discuss interests, they may state their position in unequivocal terms. You may be concerned with developing possible agreements to maximize the gains of both parties. They may be attacking your proposals, concerned only with maximizing their own gains. You may attack the problem on its merits; they may attack you. What can you do to turn them away from positions and toward the merits? There are three basic approaches for focusing their attention on the merits. The first centers on what you can do. You yourself can concentrate on the merits, rather than on positions. This method, the subject of this book, is contagious; it holds open the prospect of success to those who will talk about interests, options, and criteria. In effect, you can change the game simply by starting to play a new one. If this doesn't work and they continue to use positional bargaining, you can resort to a second strategy which focuses on what they may do. It counters the basic moves of positional bargaining in ways that direct their attention to the merits. This strategy we call negotiation jujitsu. The third approach focuses on what a third party can do. If neither principled negotiation nor negotiation jujitsu gets them to play, consider including a third party trained to focus the discussion on interests, options, and criteria. Perhaps the most effective tool a third party can use in such an effort is the one-text mediation procedure. The first approach — principled negotiation — has already been discussed. Negotiation jujitsu and the one-text procedure are explained in this chapter. The chapter ends with a dialogue based on an actual landlord-tenant negotiation that illustrates in detail how you might persuade an unwilling party to play, using a combination of principled negotiation and negotiation jujitsu. Negotiation jujitsu If the other side announces a firm position, you may be tempted to criticize and reject it. If they criticize your proposal, you may be tempted to defend it and dig yourself in. If they attack you, you may be tempted to defend yourself and counterattack. In short, if they push you hard, you will tend to push back. Yet if you do, you will end up playing the positional bargaining game. Rejecting their position only locks them in. Defending your proposal only locks you in. And defending yourself sidetracks the negotiation into a clash of personalities. You will find yourself in a vicious cycle of attack and defense, and you will waste a lot of time and energy in useless pushing and pulling. If pushing back does not work, what does? How can you prevent the cycle of action and reaction? Do not push back. When they assert their positions, do not reject them. When they attack your ideas, don't defend them. When they attack you, don't counterattack. Break the vicious cycle by refusing to react. Instead of pushing back, sidestep their attack and deflect it against the problem. As in the Oriental martial arts of judo and jujitsu, avoid pitting your strength against theirs directly; instead, use your skill to step aside and turn their strength to your ends. Rather than resisting their force, channel it into exploring interests, inventing options for mutual gain, and searching for independent standards. How does "negotiation jujitsu" work in practice? How do you sidestep their attack and deflect it against the problem? Typically their "attack" will consist of three maneuvers: asserting their position forcefully, attacking your ideas, and attacking you. Let's consider how a principled negotiator can deal with each of these. 1. Don't attack their position, look behind it. When the other side sets forth their position, neither reject it nor accept it. Treat it as one possible option. Look for the interests behind it, seek out the principles which it reflects, and think about ways to improve it. 2. Don't defend your ideas, invite criticism and advice. A lot of time in negotiation is spent criticizing. Rather than resisting the other side's criticism, invite it. Instead of asking them to accept or reject an idea, ask them what's wrong with it. Another way to channel criticism in a constructive direction is to turn the situation around and ask for their advice. Ask them what they would do if they were in your position. 3. Recast an attack on you as an attack on the problem. When the other side attacks you personally — as frequently happens — resist the temptation to defend yourself or to attack them. Instead, sit back and allow them to let off steam. Listen to them, show you understand what they are saying, and when they have finished, recast their attack on you as an attack on the problem. 4. Ask questions and pause. Those engaged in negotiation jujitsu use two key tools. The first is to use questions instead of statements. Statements generate resistance, whereas questions generate answers. Questions allow the other side to get their points across and let you understand them. They pose challenges and can be used to lead the other side to confront the problem. Questions offer them no target to strike at, no position to attack. Questions do not criticize, they educate. Silence is one of your best weapons. Use it. If they have made an unreasonable proposal or an attack you regard as unjustified, the best thing to do may be to sit there and not say a word. If you have asked an honest question to which they have provided an insufficient answer, just wait. People tend to feel uncomfortable with silence, particularly if they have doubts about the merits of something they have said. Silence often creates the impression of a stalemate which the other side will feel impelled to break by answering your question or coming up with a new suggestion. When you ask questions, pause. Don't take them off the hook by going right on with another question or some comment of your own. Some of the most effective negotiating you will ever do is when you are not talking. Consider the one-text procedure You will probably call in a third party only if your own efforts to shift the game from positional bargaining to principled negotiation have failed. One process designed to enable a third party to mediate a negotiate is known as the one-text procedure. Perhaps the most famous use of the one-text procedure was by the United States at Camp David in September 1978 when mediating between Egypt and Israel. The United States listened to both sides, prepared a draft to which no one was committed, asked for criticism, and improved the draft again and again until the mediators felt they could improve it no further. After thirteen days and some twenty-three drafts, the United States had a text it was prepared to recommend. When President Carter did recommend it, Israel and Egypt accepted. As a mechanical technique for limiting the number of decisions, reducing the uncertainty of each decision, and preventing the parties from getting increasingly locked into their positions, it worked remarkably well. The one-text procedure is a great help for two-party negotiations involving a mediator. It is almost essential for large multilateral negotiations. One hundred and fifty nations, for example, cannot constructively discuss a hundred and fifty different proposals. Nor can they make concessions contingent upon mutual concessions by everybody else. They need some way to simplify the process of decision-making. The one-text procedure serves that purpose. You do not have to get anyone's consent to start using the one-text procedure. Simply prepare a draft and ask for criticism. Again, you can change the game simply by starting to play the new one. Even if the other side is not willing to talk to you directly (or vice versa), a third party can take a draft around. CHAPTER 8. WHAT IF THEY USE DIRTY TRICKS? Taming the Hard Bargainer Principled negotiation is all very well, but what if the other negotiator deceives you or tries to throw you off balance? Or what if he escalates his demands just when you are on the verge of agreement? There are many tactics and tricks people can use to try to take advantage of you. Everyone knows some of them. They range from lies and psychological abuse to various forms of pressure tactics. They may be illegal, unethical, or simply unpleasant. Their purpose is to help the user "win" some substantive gain in an unprincipled contest of will. Such tactics may be called tricky bargaining. If they recognize that a tricky bargaining tactic is being used against them, most people respond in one of two ways. The first standard response is to put up with it. It is unpleasant to rock the boat. You may give the other side the benefit of the doubt or get angry and promise yourself never to deal with them again. For now, you hope for the best and keep quiet. Most people respond this way. They hope that if they give in this time, the other side will be appeased and will not ask for more. Sometimes this works, more often it fails. This is how Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, responded in 1938 to Hitler's negotiating tactics. After Chamberlain thought he had an agreement, Hitler raised his demands. At Munich, Chamberlain, hoping to avoid war, went along. A year later, World War II started. The second common response is to respond in kind. If they start outrageously high, you start outrageously low. If they are deceptive, so are you. If they make threats, you make counterthreats. If they lock themselves into their position, you lock yourself even more tightly into yours. In the end either one party yields or, all too often, negotiation breaks off. Such tricky tactics are illegitimate because they fail the test of reciprocity. They are designed to be used by only one side; the other side is not supposed to know the tactics or is expected to tolerate them knowingly. Earlier we argued that an effective counter to a one-sided65 substantive proposal is to examine the legitimacy of the principle that the proposal reflects. Tricky bargaining tactics are in effect one-sided proposals about negotiating procedure, about the negotiating game that the parties are going to play. To counter them, you will want to engage in principled negotiation about the negotiating process. How do you negotiate about the rules of the game? There are three steps in negotiating the rules of the negotiating game where the other side seems to be using a tricky tactic: (1) recognize the tactic, (2) raise the issue explicitly, and (3) question the tactic's legitimacy and desirability — negotiate over it. You have to know what is going on to be able to do something about it. Learn to spot particular ploys that indicate deception, those designed to make you uncomfortable, and those which lock the other side into their position. Often just recognizing a tactic will neutralize it. Realizing, for example, that the other side is attacking you personally in order to impair your judgment may well frustrate the effort. After recognizing the tactic, bring it up with the other side. Discussing the tactic not only makes it less effective, it also may cause the other side to worry about alienating you completely. Simply raising a question about a tactic may be enough to get them to stop using it. The most important purpose of bringing the tactic up explicitly, however, is to give you an opportunity to negotiate about the rules of the game. This is the third step. This negotiation focuses on procedure instead of substance, but the goal remains to produce a wise agreement (this time about procedure) efficiently and amicably. Deliberate deception Perhaps the most common form of dirty trick is misrepresentation about facts, authority, or intentions. 1. Phony facts. The oldest form of negotiating trickery is to make some knowingly false statement. The dangers of being taken in by false statements are great. What can you do? Separate the people from the problem. Unless you have good reason to trust somebody, don't. This does not mean calling him a liar; rather it means making the negotiation proceed independent of trust. Do not let someone treat your doubts as a personal attack. No seller is likely to give you a watch or a car simply in exchange for your statement that you have money in the bank. Just as a seller will routinely check on your credit ("because there are so many other people around that can't be trusted"), you can do the same for statements of the other side. A practice of verifying factual assertions reduces the incentive for deception, and your risk of being cheated. 2. Ambiguous authority. The other side may allow you to believe that they, like you, have full authority to compromise when they don't. After they have pressed you as hard as they can and you have worked out what you believe to be a firm agreement, they announce that they must take it to someone else for approval. This technique is designed to give them a "second bite at the apple." This is a bad situation to fall into. If only you have authority to make concessions, only you will make concessions. Do not assume that the other side has full authority just because they are there negotiating with you. An insurance adjuster, lawyer, or a salesman may allow you to think that your flexibility is being matched by flexibility on their side. You may later find that what you thought was an agreement will be treated by the other side as simply a floor for further negotiation. Before starting on any give-and-take, find out about the authority of the other side. It is perfectly legitimate to inquire, "Just how much authority do you have in this particular negotiation?" If the answer is ambiguous, you may wish to talk to someone with real authority or to make clear that you on your side are reserving equal freedom to reconsider any point. If they do announce unexpectedly that they are treating what you thought was an agreement as a basis for further negotiation, insist on reciprocity. "All right. We will treat it as a joint draft to which neither side is committed. You check with your boss and I'll sleep on it and see if I come up with any changes I want to suggest tomorrow." Or you might say, "If your boss approves this draft tomorrow, I'll stick by it. Otherwise each of us should feel free to propose changes." 3. Dubious intentions. Where the issue is one of possible misrepresentation of their intention to comply with the agreement, it is often possible to build compliance features into the agreement itself. Suppose you are a lawyer representing the wife in a divorce negotiation. Your client does not believe her husband will pay child support even though he may agree to do so. The time and energy spent in going to court every month may make her give up the effort. What can you do? Make the problem explicit and use their protestations to get a guarantee. You could say to the husband's lawyer, "Look, my client is afraid those child support payments simply aren't going to be made. Rather than monthly payments, how about giving her equity in the house?" The husband's lawyer may say, "My client is perfectly trustworthy. We'll put it in writing that he will pay child support regularly." To which you might respond, "It's not a matter of trust. Are you certain that your client will pay?" "Of course." "A hundred percent certain?" "Yes, I'm a hundred percent certain." "Then you won't mind a contingent agreement. Your client will agree to make child support payments. We'll provide that if, for some inexplicable reason which you estimate at zero percent probability, he misses two payments, my client will get the equity in the house (minus of course the amount your client has already paid out in child support) and your client will no longer be liable for child support." It is not easy for the husband's lawyer to object. Less than full disclosure is not the same as deception. Deliberate deception as to facts or one's intentions is quite different from not fully disclosing one's present thinking. Good faith negotiation does not require total disclosure. Perhaps the best answer to questions such as "What is the most you would pay if you had to?" would be along the following lines: "Let's not put ourselves under such a strong temptation to mislead. If you think no agreement is possible, and that we may be wasting our time, perhaps we could disclose our thinking to some trustworthy third party, who can then tell us whether there is a zone of potential agreement." In this way it is possible to behave with full candor about information that is not being disclosed. Psychological warfare These tactics are designed to make you feel uncomfortable, so that you will have a subconscious desire to end the negotiation as soon as possible. Stressful situations. Much has been written about the physical circumstances in which negotiations take place. You should be sensitive to such modest questions as whether a meeting takes place at your place or theirs, or on neutral territory. Contrary to the accepted wisdom, it is sometimes advantageous to accept an offer to meet on the other side's turf. It may put them at ease, making them more open to your suggestions. If necessary, it will be easier for you to walk out. If, however, you do allow the other side to choose the physical environment, be aware of what that choice is and what effects it may have. Ask yourself if you feel under stress, and if so, why. If the room is too noisy, if the temperature is too hot or cold, if there is no place for a private caucus with a colleague, be aware that the setting might have been deliberately designed to make you want to conclude negotiations promptly and, if necessary, to yield points in order to do so. If you find the physical surroundings prejudicial, do not hesitate to say so. You can suggest changing chairs, taking a break, or adjourning to a different location or another time. In every case your job is to identify the problem, be willing to raise it with the other side, and then negotiate better physical circumstances in an objective and principled fashion. Personal attacks. In addition to manipulating the physical environment, there are also ways for the other side to use verbal and nonverbal communication to make you feel uncomfortable. They can comment on your clothes or your appearance. "Looks like you were up all night. Things not going well at the office?" They can attack your status by making you wait for them or by interrupting the negotiations to deal with other people. They can imply that you are ignorant. They can refuse to listen to you and make you repeat yourself. They can deliberately refuse to make eye contact with you. (Simple experiments with students have confirmed the malaise many feel when this tactic is used; and they are unable to identify the cause of the problem.) In each case recognizing the tactic will help nullify its effect; bringing it up explicitly will probably prevent a recurrence. The good-guy/bad-guy routine. One form of psychological pressure which also involves deception is the good-guy/bad-guy routine. This technique appears in its starkest form in old police movies. The first policeman threatens the suspect with prosecution for numerous crimes, puts him under a bright light, pushes him around, then finally takes a break and leaves, The good guy then turns off the light, offers the suspect a cigarette, and apologizes for the tough policeman. He says he'd like to control the tough guy, but he can't unless the suspect cooperates. The result: the suspect tells all he knows. Similarly in a negotiation, two people on the same side will stage a quarrel. One will take a tough stand: "These books cost $8,000, and I won't accept a penny less." His partner looks pained and a little embarrassed. Finally he breaks in: "Frank, you are being unreasonable. After all, these books are two years old, even if they haven't been used much." Turning to the other side, he says reasonably, "Could you pay $7,600?" The concession isn't large, but it almost seems like a favor. The good-guy/bad-guy routine is a form of psychological manipulation. If you recognize it, you won't be taken in. When the good guy makes his pitch, just ask him the same question you asked the bad guy: "I appreciate that you are trying to be reasonable, but I still want to know why you think that's a fair price. What is your principle? I am willing to accept $8,000 if you can persuade me it's the fairest price." Threats. Threats are one of the most abused tactics in negotiation. A threat seems easy to make — much easier than an offer. All it takes is a few words, and if it works, you never have to carry it out. But threats can lead to counterthreats in an escalating spiral that can unhinge a negotiation and even destroy a relationship. Threats are pressure. Pressure often accomplishes just the opposite of what it is intended to do; it builds up pressure the other way. Instead of making a decision easier for the other side, it often makes it more difficult. In response to outside pressure, a union, a committee, a company, or a government may close ranks. Moderates and hawks join together to resist what they may perceive as an illegitimate attempt to coerce them. The question changes from "Should we make this decision?" to "Shall we cave in to outside pressure?" Good negotiators rarely resort to threats. They do not need to; there are other ways to communicate the same information. If it seems appropriate to outline the consequences of the other side's action, suggest those that will occur independently of your will rather than those you could choose to bring about. Warnings are much more legitimate than threats and are not vulnerable to counterthreats: "Should we fail to reach agreement, it seems highly probable to me that the news media would insist on publishing the whole sordid story. In a matter of this much public interest, I don't see how we could legitimately suppress information. Do you?" For threats to be effective they must be credibly communicated. Sometimes you can interfere with the communication process. You can ignore threats; you can. take them as unauthorized, spoken in haste, or simply irrelevant. You can also make it risky to communicate them. At a coal mine where one of the authors was recently mediating, a large number of false but costly bomb threats were being received. These dropped off dramatically when the company's receptionist began answering all phone calls with "Your voice is being recorded. What number are you calling?" Sometimes threats can be turned to your political advantage. A union could announce to the press: "Management has such a weak case that they are resorting to threats." Perhaps the best response to a threat, however, is to be principled. "We have prepared a sequence of countermoves for each of management's customary threats. However, we have delayed taking action until we see whether we can agree that making threats is not the most constructive activity we could engage in just now." Or "I only negotiate on the merits. My reputation is built on not responding to threats." Positional pressure tactics This kind of bargaining tactic is designed to structure the situation so that only one side can effectively make concessions. Refusal to negotiate. When the American diplomats and embassy personnel were taken hostage in Tehran in November 1979, the Iranian government announced its demands and refused to negotiate. A lawyer will often do the same, simply telling opposing counsel, "I'll see you in court." What can you do when the other side refuses to negotiate altogether? First, recognize the tactic as a possible negotiating ploy: an attempt to use their entry into negotiation as a bargaining chip to obtain some concession on substance. A variant on this ploy is to set preconditions for negotiations. Second, talk about their refusal to negotiate. Communicate either directly or through third parties. Don't attack them for refusing to negotiate, but rather find out their interests in not negotiating. Are they worried about giving you status by talking to you? Will those who talk with you be criticized for being "soft"? Do they think negotiation will destroy their precarious internal unity? Or do they simply not believe that an agreement is possible? Suggest some options, such as negotiating through third parties, sending letters, or encouraging private individuals like journalists to discuss the issues (as happened in the Iranian case). Finally, insist on using principles. Is this the way they would want you to play? Do they want you to set preconditions as well? Will they want others to refuse to negotiate with them? What are the principles they think should apply to this situation? Extreme demands. Negotiators will frequently start with extreme proposals like offering $75,000 for your house which is apparently worth $200,000. The goal is to lower your expectations. They also figure that an extreme initial position will give them a better end result, on the theory that the parties will ultimately end up splitting the difference between their positions. There are drawbacks to this approach, even for tricky bargainers. Making an extreme demand that both you and they know will be abandoned undermines their credibility- Such an opening may also kill the deal; if they offer too little, you may think they are not worth bothering with. Bringing the tactic to their attention works well here. Ask for principled justification of their position until it looks ridiculous even to them. Escalating demands. A negotiator may raise one of his demands for every concession he makes on another. He may also reopen issues you thought had been settled. The benefits of this tactic lie in decreasing the overall concession, and in the psychological effect of making you want to agree quickly before he raises any more of his demands. The Prime Minister of Malta used this tactic in negotiating with Great Britain in 1971 over the price of naval and air base rights. Each time the British thought they had an agreement, he would say, "Yes, agreed, but there is still one small problem." And the small problem would turn out to be a £10 million cash advance or guaranteed jobs for dockyard and base workers for the life of the contract. When you recognize this, call it to their attention and then perhaps take a break while you consider whether and on what basis you want to continue negotiations. This avoids an impulsive reaction while indicating the seriousness of their conduct. And again, insist on principle. When you come back, anyone interested in settlement will be more serious. Lock-in tactics. This tactic is illustrated by Thomas Schelling's well-known example of two dynamite trucks barreling toward each other on a single-lane road. The question becomes which truck goes off the road to avoid an accident. As the trucks near each other, one driver in full view of the other pulls off his steering wheel and throws it out the window. Seeing this, the other driver has a choice between an explosive crash or driving his truck off the road into a ditch. This is an example of an extreme commitment tactic designed to make it impossible to yield. Paradoxically, you strengthen your bargaining position by weakening your control over the situation. In labor-management and international negotiations this tactic is common. A union president makes a rousing speech to his constituency pledging that he will never accept less than a 15 percent salary increase. Since he stands to lose face and credibility if he does agree to anything less, he can more convincingly persuade management the union must have 15 percent. But lock-in tactics are gambles. You may call the other side's bluff and force them to make a concession which they will then have to explain to their constituency. Like threats, lock-in tactics depend on communication. If the other truck driver does not see the steering wheel fly out the window, or if he thinks the truck has an emergency steering mechanism, the act of throwing the steering wheel out the window will not have its intended effect. The pressure to avoid a collision will be felt equally by both drivers. In response to a commitment tactic, therefore, you may be able to interrupt the communication. You can so interpret the commitment as to weaken it. "Oh I see. You told the papers your goal was to settle for $200,000. Well, we all have our aspirations, I guess. Do you want to know what mine are?" Alternatively, you can crack a joke and not take the lock-in seriously. You can also resist lock-ins on principle: "Fine, Bob, I understand you made that statement publicly. But my practice is never to yield to pressure, only to reason. Now let's talk about the merits of the problem." Whatever you do, avoid making the commitment a central question. Deemphasize it so that the other side can more gracefully back down. Hardhearted partner. Perhaps the most common negotiating tactic used to justify not yielding to your requests is for the other negotiator to say that he personally would have no objection but his hardhearted partner will not let him. "It's a perfectly reasonable request, I agree. But my wife absolutely refuses to go along with me on it." Recognize the tactic. Rather than discussing it with the other negotiator, you may want to get his agreement to the principle involved — perhaps in writing — and then if possible speak directly with the "hardhearted partner." A calculated delay. Frequently one side will try to postpone coming to a decision until a time they think favorable. Labor negotiators will often delay until the last few hours before a strike deadline, relying on the psychological pressure of the deadline to make management more malleable. Unfortunately, they often miscalculate and the strike deadline passes. Once the strike begins, management, in turn, may decide to wait for a more favorable time, such as when the union's strike fund has run out. Waiting for the right time is a high-cost game. In addition to making delaying tactics explicit and negotiating about them, consider creating a fading opportunity for the other side. If you represent one company negotiating a merger with another, start talks with a third company, exploring the possibility of merging with them instead. Look for objective conditions that can be used to establish deadlines, such as the date on which taxes are due, the annual trustees meeting, the end of the contract, or the end of the legislative session. "Take it or leave it." There is nothing inherently wrong with confronting the other side with a firm choice. In fact, most American business is conducted this way. If you go into a supermarket and see a can of beans marked 75 cents, you don't try to negotiate with the supermarket manager. This is an efficient method of conducting business, but it is not negotiation. It is not interactive decision-making. Nor is there anything wrong after long negotiations to conclude them when you mean to do so by saying, "Take it or leave it," except that you should probably phrase it more politely. As an alternative to explicitly recognizing the "Take it or leave it" tactic and negotiating about it, consider ignoring it at first. Keep talking as if you didn't hear it, or change the subject, perhaps by introducing other solutions. If you do bring up the tactic specifically, let them know what they have to lose if no agreement is reached and look for a face-saving way, such as a change in circumstances, for them to get out of the situation After management has announced its final offer, the union could tell them, "A $1.69 raise was your final offer before we discussed our cooperative efforts to make the plant more productive." Don't be a victim It is often hard to decide what it means to negotiate in "good faith." People draw the line in different places. It may help to ask yourself such questions as: Is this an approach I would use in dealing with a good friend or a member of my family? If a full account of what I said and did appeared in the newspapers, would I be embarrassed? In literature, would such conduct be more appropriate for a hero or a villain? These questions are not intended to bring external opinion to bear so much as to shed light on your own internal values. You must decide on your own whether you want to use tactics you would consider improper and in bad faith if used against you. It may be useful at the beginning of the negotiation to say, "Look, I know this may be unusual, but I want to know the rules of the game we're going to play. Are we both trying to reach a wise agreement as quickly and with as little effort as possible? Or are we going to play 'hard bargaining' where the more stubborn fellow wins?" Whatever you do, be prepared to fight dirty bargaining tactics. You can be just as firm as they can, even firmer. It is easier to defend principle than an illegitimate tactic. Don't be a victim.