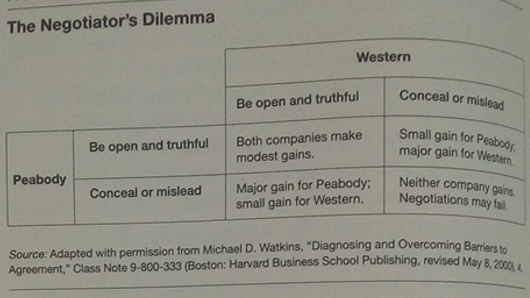

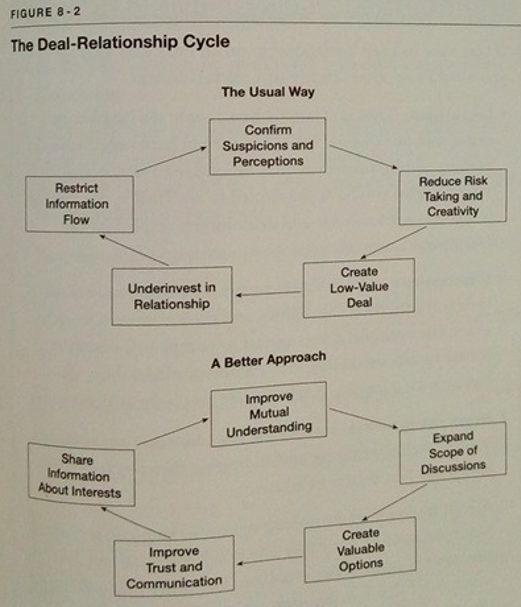

CHAPTER 1: TYPES OF NEGOTIATION The Latin root (negotiatus) of the word 'negotiation' means "to carry on business". In modern Spanish, negocios means "business". ~ ~ ~ THERE ARE two primary kinds of negotiation. Chances are you have been involved in both at one time or another: Distributive: A negotiation in which the patties compete over the distribution of a fixed sum of value. The key question in a distributed negotiation is "Who will claim the most value?". In distributive negotiations, a gain by one side is made at the expense of the other. Integrative: A negotiation in which the parties cooperate to achieve maximum benefits by integrating their interests into an agreement. These deals are about creating value and claiming it. ~ ~ ~ DISTRIBUTIVE NEGOTIATION To achieve success in a distributive negotiation, remember the following: 1. The first offer can become a strong psychological anchor point, one that sets the bargaining range. Studies show that negotiation outcomes often correlate with the first offer. So, start at the right place. 2. Do not disclose any significant information about your circumstances - including why you want to make a deal, your real interests or business constraints, your preferences among issues or options, or the point at which you'd walk away from the table. It is advantageous, however, to let the other side know that you have good options if this deal falls through. 3. Information about the other side can benefit you. Learn as much as possible about the other side's circumstances and preferences - including why they want to make a deal, their real interests and business constraints, and their preferences among issues or options. 4. Exploit what you learn about the other side in setting your first offer or demand. 5. Don't overshoot. If you claim aggressively or greedily, the other side may walk away. You will have lost the opportunity to make a deal. ~ ~ ~ INTEGRATIVE NEGOTIATION In an integrative negotiation, your task is twofold: (1) to create as much value as possible for you and for the other side, and (2) to claim value for yourself. Finding opportunities for mutual benefit naturally requires information sharing. Unlike the distributive situation, in which you deliberately play your cards close to the vest, an integrative negotiation encourages negotiators to do the following: 1) Provide significant information about their circumstances. 2) Explain why they want to make a deal. 3) Talk about their real interests or business constraints. 4) Reveal and explain in general terms their preferences among issues or options. 5) Consider and reveal any additional capabilities or resources they have that might meet the other side's interests and could be added to the deal. 6) Use what they learn to find creative options that will meet the interests of both parties to the greatest extent possible. ~ ~ ~ SUMMING UP 1. A distributive negotiation pits two or more parties in competition for a fixed amount of value. Here, each side's goal is to claim as much value as possible, as in the sale of a rug at a street bazaar. Value gained by one party is unavailable to others. 2. Integrative negotiation is about creating and claiming value. Through collaboration and information sharing, the parties look for opportunities to satisfy the key objectives of each, recognizing that they will probably have to give ground on other objectives. 3. The negotiator's dilemma describes the situation faced by people who enter any type of bargaining situation. They must determine which game to play aggressively claim the value currently on the table (and possibly come out the loser), or work with the other side to create even better opportunities that can be shared. 4. No matter which type of negotiation you're faced with, it's bound to be more complex if it has multiphases or involves multiple parties. If your negotiation is multiphased, use the early phases to build trust and to become familiar with the other parties. If many parties are involved, consider the benefits of forming a coalition to improve your bargaining power. ~ ~ ~ CHAPTER 2: FOUR KEY CONCEPTS 1. Know Your BATNA BATNA is one's preferred course of action in the absence of a deal. Knowing your BATNA means knowing what you will do or what will happen if you fail to reach agreement in the negotiation at hand. % IMPROVING YOUR POSITION: 1. Improve your BATNA. 2. Identify the other side's BATNA. 3. Weaken the other party's BATNA. % A CAUTION ON BATNA VALUES Although it's absolutely essential that you know your own BATNA and try to estimate that of the other side, be aware that most people don't do a good job of estimating BATNA values. For example, Lax and Sebenius describe an experiment involving the value of a company up for sale. "Even given identical business information, balance sheets, income statements, and the like," they write, "those assigned to buy the company typically rate its true value as low, while those assigned to sell it give much higher best estimates. Neutral observers tend to rank the potential someplace in between." The lesson here is that BATNA values can be influenced by your personal perspective. So be as objective as possible. Check your thinking with a neutral third party. % No negotiator is in a weaker position than one with no alternative to a deal. In this case, the other side can dictate the terms. The BATNA-less party is a deal taker, not a deal maker. 2. RESERVATION PRICE The reservation price (also referred to as the walk-away) is the least favorable point at which one will accept a deal. Your reservation price should be derived from your BATNA, but it is not usually the same thing. If the deal is only about money, however, and a credible dollar offer is your BATNA, then your reservation price would be approximately equal to your BATNA. Consider the following example: You are currently paying $20 per square foot for suburban office space. The location is satisfactory, and you believe that the price is fair, but you wouldn't mind paying more to be closer to your downtown customers. While preparing to negotiate with a commercial landlord for an offer lease in a downtown high-rise, you decided that you would not pay more than $30 per square foot. That's your reservation price. If the landlord insists on more, you can walk away and attempt to lease space in a different building. Or you can stay where you are at $20 per square foot (your BATNA). At the end of a lengthy negotiation session, the landlord declares that he will not accept less than $35 per square foot - and he won't budge. You graciously terminate the negotiation and walk away from the deal. In this example your reservation price is different from your BATNA. BATNA in this case is the current rent at the current location: $20 per square foot. But the new location has different characteristics that enter into the equation. It's closer to customers, and it may be a more attractive space with greater workplace utility. You'd be willing to assume the added expense and the hassle of moving, even if it meant paying $30 per square foot. Anything more than that, however, would be unacceptable. Thus, there's a subtle difference between your BATNA and your reservation price. The fact that the prospective landlord would not take less than $35 per square foot suggests that $35 is his reservation price. 3. ZOPA ZOPA, or zone of possible agreement, is the area or range in which a deal that satisfies both parties can take place. Put another way, it is the set of agreements that potentially satisfy both parties. 4. Value Creation Through Trades Another fundamental concept of negotiation is value creation through trades. This concept tells us that negotiating parties can improve their positions by trading the values at their disposal. Value creation through trade occurs in the context of integrated negotiations. It usually takes the form of each party getting something it wants in return for something it values much less. SUMMING UP This chapter has explained the fundamental concepts used by skilled negotiators. 1. BATNA is the best alternative to a negotiated agreement. It is one's preferred course of action in the absence of deal. Knowing your BATNA means knowing what you will do or what will happen if you fail to reach agreement. Don't enter a negotiation without knowing your BATNA. 2. If your BATNA is weak, do what you can to improve it. Anything that strengthens your BATNS improves your negotiating position. 3. Identify the other side's BATNA. If it is strong, think of what you can do to weaken it. 4. Reservation price is the price at which the rational negotiator will walk away. Don't enter a negotiation without a clear reservation price. 5. ZOPA is the zone of possible agreement. It is the area in which a deal will satisfy all parties. This area exists when the parties have different reservation prices, as when a home buyer is willing to pay up to $275K and the home seller is willing to take an offer that is at least $250K. 6. Value creation through trades is possible when a party has something he or she values less than does the other party - and vice versa. By trading these values, the parties lose little but gain greatly. ~ ~ ~ CHAPTER 3: PREPARATION NINE STEPS TO A DEAL Every important endeavor benefits from preparation. Negotiating is no different. People who know what they want, what they are willing to settle for, and what the other side is all about stand a better chance of negotiating a favorable deal for themselves. STEP 1: CONSIDER WHAT A GOOD OUTCOME WOULD BE FOR YOU AND THE OTHER SIDE Never enter into a negotiation without first asking yourself, "What would be a good outcome for me? What are my needs, and how do I prioritize them?" Then ask the same question from the perspective of the other side. % The interests of the two sides are sometimes revealed through dialogue at the negotiating table. But not always - particularly in win-lose distributive deals. If you cannot identify the other side's interests, use every communication opportunity to probe for them. STEP 2: IDENTIFY POTENTIAL VALUE CREATION OPPORTUNITIES STEP 3: IDENTIFY YOUR BATNA AND RESERVATION PRICE, AND DO THE SAME FOR THE OTHER SIDE STEP 4: SHORE UP YOUR BATNA STEP 5: ANTICIPATE THE AUTHORITY ISSUE "Car dealer" trick: where just as you are about to reach agreement with the salesman, he says, "I will have to clear this with my manager." In other words, the negotiation with the salesman is used to bring you to your bottom line; the second negotiation, with the manager, aims to push you beyond it. There are real advantages to negotiating with the person who has the power to sign on the dotted line: a) All of your reasoning is heard directly by the decision maker. b) The benefits of the good relationship built at the bargaining table are likely to be reflected in the deal and its implementation. c) There are fewer chances of disputes or misrepresentation of particular provisions. d) You avoid the "car dealer" trick described previously. e) If your aim is to make the person on the other side of the table hungry for a deal with you, your efforts will do no good if the real decision maker is somewhere in the background. STEP 6: LEARN ALL YOU CAN ABOUT THE OTHER SIDE'S PEOPLE AND CULTURE, THEIR GOALS, AND HOW THEY'VE FRAMED THE ISSUE STEP 7: PREPARE FOR FLEXIBILITY IN THE PROCESS - DON'T LOCK YOURSELF INTO A RIGID SEQUENCE Here are some things you can do to be more flexible in negotiations: a) Start with the assumption that the process will not unfold in a predictable, linear fashion. b) Be prepared for changes on both sides: new people and unanticipated developments. c) Treat every change as an opportunity for learning. STEP 8: GATHER EXTERNAL STANDARDS AND CRITERIA RELEVANT TO FAIRNESS STEP 9: ALTER THE PROCESS IN YOUR FAVOR Have you ever felt that your ideas were being ignored during meetings or formal negotiations? Does it ever appear that these meetings are rigged to produce a particular result - in spite of input by you or others? If you have, consider these possible explanations: a) Whoever set the agenda did so with a particular outcome in mind - one that benefits that person or entity. b) People are deferring to someone with greater organizational clout - your arguments notwithstanding. c) Yours is a 'lone voice in the wilderness' and out of step with others. Any of these explanations can shut you out and steer results in a direction favored - if not rigged - by someone else. The antidote is to work away from the table to change the process. "Process moves," as described by Deborah Kolb and Judith Williams, "do not address the substantive issues in a negotiation." Instead, they directly affect the hearing those issues receive. "The agenda, the pre-negotiation groundwork, and the sequence in which ideas and people are heard - all these structural elements influence other's receptivity to opinions and demands." If you've ever followed international conflict negotiations on the evening news, you've probably noticed that experienced diplomats don't jump right into the issues. Instead, they spend months trying to agree where the meeting will take place, who will participate, and even the shape of the negotiating table. These are all process moves, and effective preparation includes attention to these away-from-the-table issues. Kolb and Williams make these specific recommendations about process moves: a) WORK BEHIND THE SCENES TO EDUCATE OTHERS ON YOUR IDEAS A formal meeting is not always a good venue for making a detailed case, or for holding dialogue about a complex issue - especially when opponents control the agenda. So, educate other participants one on one outside formal meetings. Concentrate on people who are respected centers of influence. Convince these people that your ideas have merit, and they will back you when opponents try to ignore your position during meetings. Better still, form a coalition of support outside the negotiations. b) REFRAME THE PROCESS If you're been marginalized in a series of meetings or negotiations, the process may be the reason. Consider this example: A loud and brash department head has framed an upcoming meeting in terms of her need for more resources - resources that will have to come from your department. She's prepared to wrestle for as much as she can get, confident that others at the meeting will be neutral because they will not be affected. You could counter by reframing the discussion from "her needs" to "the company's needs". This would make you appear levelheaded and statesmanlike and would help others recognize that the department head's resource grab also affects them. SUMMING UP If your aim is to be an effective negotiator, take the time and make the effort needed to become fully prepared. This chapter has offered nine preparatory steps: 1. Know what a good outcome would be from your point of view and that of the other side. 2. Look for opportunities to create value in the deal. 3. Know your BATNA and reservation price. Make an effort to estimate those benchmarks for the other side. 4. If your BATNA isn't strong, find ways to improve it. 5. Find out if the person or team you're dealing with has the authority to make a deal. 6. Know those with whom you're dealing. Learn as much as you can about the people and the culture on the other side and how they've framed the issue. 7. If a future relationship with the other side matters, gather the external standards and criteria that will show your offer to be fair and reasonable. 8. Don't expect things to follow a linear path to a conclusion. Be prepared for bumps in the road and periodic delays. 9. Alter the agenda and process moves in your favor. ~ ~ ~ CHAPTER 4: TABLE TACTICS HOW TO PLAY THE GAME WELL Getting the Other Side to the Table Before we get into actual negotiating tactics, let's consider some tactics for getting the other side to negotiate. In many cases, issues you may want to negotiate cannot move forward because one or more parties simply aren't interested - they are satisfied with the status quo. They see no point in negotiating with you. And if they have greater organizational power than you, they may brush you off with these types of comments: "I don't think there is any reason to consider this - things are fine," or "We're so tied up with the budget that I won't be able to consider that until next spring at the earliest." Kolb and Williams note: "Such resistance is natural part of the informal negotiation process. A concern will generally be accorded a fair hearing only when someone believes two things: the other party has something desirable, and one's own objectives will not be met without giving something in return. Willingness to negotiate is, therefore, a confession of mutual need." More precisely, resisters must conclude that they will be better off if they negotiate and worse off if they do not. Kolb and Williams suggest three things you can do to help reluctant bargainers reach this conclusion: 1. Offer incentives. What are the reluctant person's needs: money, time, your support? Determine those needs and then pose them as potential benefits of negotiation. For example, if your boss, the sales manager, is reluctant to give you time to work on a redesign of the company's inventory system, explain how an improved system will help solve one of his problem - lost sales from out-of-stock conditions. 2. Put a price on the status quo. Spell out the cost of not negotiating. Kolb and Williams use the example of a woman whose boss promoted her and had her take on additional work but was forever delaying any discussion of a pay raise. Frustrated by his inaction, she found a way to get his attention - she secured a job offer from another company. The boss was suddenly very interested in dealing with her long overdue pay raise. He had to negotiate or face the costly and time-consuming process of replacing an effective subordinate. In other words, he realized the price of the status quo. 3. Enlist support. Allies can sometimes accomplish what other measure cannot. For example, if the sales manager described earlier still will not give you time off to improve the inventory system, look for allies who have organizational power and a reason to favor your goal. The chief financial officer, for instance, will likely favor any plan to improve inventory management. The CFO knows that better inventory management means lower working capital requirement, which makes her look good. Once the sales manager realizes that the issue has risen to the senior management level, he's likely to bargain. Making a Good Start Once you've gotten the other side to the bargaining table, it's important to get things off to a smooth start. That begins with relieving the tension that is often present. In your opening remarks, try to relieve that tension: 1. Express respect for the other side's experience and expertise. 2. Frame the task positively, as a joint endeavor. 3. Emphasize your openness to the other side's interests and concerns. Tips for Establishing the Right Tone The negotiation environment can affect the level of tension and openness that prevails. If you're interested in lowering tension and seeking collaborative discussion, follow these tips: 1. Never underestimate the value of "breaking bread". In practically every culture, breaking bread is a bonding ritual. So have coffee, soft drinks, and light snacks available. 2. Use small talk at the beginning to dispel tension, lower people's natural defenses, and begin the process of building relationships. Even is a win-lose negotiation, small talk helps the different sides know each other better and gauge each other's truthfulness. It may also loosen people up to the point of seeking value-creating opportunities. 3. Learn from what the small talk reveals about the other negotiator's style and manner. 4. If the other side is very formal, don't speak too casually - they may interpret this as a lack of seriousness on your part. If the other side is decidedly informal, speak in a more casual way, perhaps using metaphors with which they are comfortable. ~ ~ ~ After these opening remarks, start with the agenda, making sure both parties have a common understanding of the issues to be covered. Then, explicitly discuss the process, especially since people often hold different assumptions about how the negotiation should work. Some assume that there will be haggling. Some expect proposals to be make at the outset, while others expect an open discussion of the issues to come first. Listen carefully to the discussion of process - it will tell you a great deal about the other side's negotiating style. Offer to explain some of your interests and concerns first. This is a good-faith demonstration that you are prepared to disclose information, provided that the exchange is reciprocal. If the other side does not reciprocate with information, be very cautious about providing more information. ~ ~ ~Tactics for Win-Lose Negotiations

1. Anchoring Anchoring is an attempt to establish a reference point around which negotiations will make adjustments. In some cases, you can gain an advantage by putting the first offer on the table. That first offer can become a strong psychological anchor: It becomes the reference point of subsequent pulling and pushing by the participants. Initial positions affect each side's perception of what outcomes are possible. When should you anchor? It may be tactically smart to anchor when you have a reasonably good sense of the other side's reservation price. If you are very uncertain about the other side's reservation price, you might encourage him or her to make the first move. Where should you place your anchor? In a negotiation in which claiming maximum value is the primary goal, your first offer or proposal should be at or just a bit beyond what you believe is the other side's reservation price, which may be determined through pre-negotiation investigation or through direct probing of the other side. Wherever you place the anchor, be prepared to articulate why your offer or proposal is reasonable or justifiable. Anchoring with a price (or a proposal) creates two risks. First, if you are too aggressive, the other side may conclude it will be impossible to make a deal with you. They may also feel personally insulted by your offer. Second, if you've made an erroneous estimate of the other side's reservation price, your offer will be outside the zone of possible agreement. If you fall afoul of either of these risks, have a different line of reasoning ready to support your shift to a less aggressive offer. "Because of the owner's desire to conclude the sale sooner than later, he has authorized me to reduce the price to..." Putting a price or proposal on the table is not the only way to gain advantage through anchoring. If you can define the issues, establish the agenda, or somehow impose your conceptual framework on the debate, you will have accomplished something very similar, and very beneficial to you. Negotiations will then proceed along a path that you have determined. 2. Counteranchoring If the other side makes the first offer, you should recognize and resist that offer's potential power as a psychological anchor. Remember that anchors are most powerful when uncertainty is highest - for example, when no one has a clear idea what the price of a company or a piece of equipment should be. When no one has a clue as to the appropriate price, there is no basis for disputing the merits of the first offer. You can reduce the other side's anchoring power by reducing the uncertainty that surrounds the issue. That means gathering and bringing objective information to the bargaining table. Don't let the other side set the bargaining range with an anchor unless you think it's a sensible starting point. If you think the anchor suggests an unfavorable or unacceptable starting point. If you think the anchor suggests an unfavorable starting point, steer the conversation away from numbers and proposals. Focus instead on interests, concerns, and generalities. Then, after some time has passed and more information has surfaced, put your number or your proposal on the table, and support it with sound reasoning. To see how this might be done, let's replay the example of Jake and his lake house. But this time, let's assume that only one potential buyer, Carla, steps forward. The real estate agent had just listed Jake's lakefront summer house for $395,000, confident that that number would be a firm anchor point for all incoming bids. But he hadn't counted on dealing with Carla. Carla had had her eye on the lakefront property market in the Deer Tail Lake area for the past two years, so she was familiar with all the current property listings and the dozens that had sold over that time period. During her first meeting with Jake's agent, Carla explained how she had been tracking property prices on Deer Tail Lake and neighboring lakes for the past two years. Without making any reference to Jake's $395,000 asking price, she cited three sales of comparable properties that had occurred on Deer Tail Lake during the past year, indicating how those properties were more or less similar to Jake's. "These three are very comparable to your listing in terms of shoreline frontage, lot sizes, and house characteristics," she told the agent as she showed him the listing sheets. "They sold for $325,000, $330,000 and $345,000, respectively, within the past ten months. Factoring in inflation, that makes your client's property worth about $350,000 at the most, which is what I'm prepared to offer you today." Here, Carla placed her own anchor on the board. Instead of focusing on what Jake wanted from the deal, she ignored his initial price, substituting in its place a new price supported by market data. That relevant data gave her anchor greater authority than Jake’s and made it easier to push his aside. In the absence of other buyers - particularly buyers who hadn't done their homework - Jake and his agent had to deal with Carla in terms of her stated offer. She effectively substituted her anchor for Jake's. The lesson of this tale is to avoid direct comparison between the other side's initial offer and your own. If the initial offer is not serious or realistic, you can safely ignore it; there's a good chance that the other side will do the same. If the initial offer was serious, and the other side refers to it again, you should respectfully ask them to explain why the offer is reasonable. "Why are you asking for $395,000 in this market? Could you explain how you are justifying that price?" 3. Be Prepared for Concessionary Moves Once an anchor point is on the table, the parties generally engage in a set of moves and countermoves that they hope will end in an agreeable price or set of arrangements. For example, if Carla in the previous example offered $350,000 for Jake's lakefront property, Jake more than likely would respond with a counteroffer through his agent, say, $385,000: "We appreciate the research you've done on recent lake property sales, Carla, but we don't feel that the properties you've used as benchmarks are really comparable to Jake's place. After all, he has that big pier and boathouse - and the house itself has been recently renovated. Taking those factors into account, we think that Jake's property is worth substantially more than your offer, and we believe that other buyers will share our view. However, in the interest of getting things wrapped up, Jake is willing to lower his price by $10,000 to $385,000." Negotiation experts generally interpret a large concessionary move as an indication of significant additional flexibility. Give a large concession, and the other side will think that you're capable of making additional large concessions. Thus, Carla may think "If Jake is willing to come down $10,000 in this first counteroffer, he's probably prepared to come down at least another $10,000." A small move, on the other hand, is generally perceived as an indication that the bidding is approaching that party's reservation price, and that further pushing will result in smaller and smaller concessions. These assumptions are not always true, especially when the other side is in no hurry, and when it has confidence that other parties may come forward with attractive prices or conditions - that is, when it has a strong BATNA. This may be the case in our example. A $10,000 concession on Jake's property isn't a huge concession, even though Carla's bid has satisfied his $350,000 reservation price. We can almost hear Jake's voice as he speaks with his agent over the phone: "I'm happy that we have an offer of $350,000 already. I could live with that. But we may get a better offer in the next week or so, either from Carla or from another buyer. Actually, I'd expect Carla to up her bid to $360K. If she does that, should we push for a bit more? Should we say, 'Give us $365K and we'll have a deal?' Or should we sit on her offer and hope to get a better one?" Jake's uncertainty about how far to push Carla in this example is a function of his uncertainty about her BATNA and reservation price. If he could estimate these with confidence, he could drive a harder bargain. In this case, Carla's BATNA may be the price of similar properties on Deer Tail Lake or other nearby lakes. He could ask his agent to come up with a list of other similar properties on those lakes. Those might represent the set of Carla's alternatives. The best advice about concessions is to avoid the impulse to make them. Few of us like negotiating, so we want to get it over as quickly as possible. And as social creatures we want other people to like us, and to view us as reasonable. These factors often make inexperienced negotiators too ready to make concessions. If you find yourself in this category, here are a few tips: 1% Look to your BATNA before you consider making a concession. If your BATNA is very strong (especially relative to the other side's), a concession may be unnecessary in making a deal. 2% If you're impatient to get it over with because negotiating is stressful, take a break before you consider a concession. If the other side is expecting a $10,000 concession on the price of the home you're selling, think about how difficult it was for you to earn that $10,000. Think about the good things you could do with the $10,000 the other would like you to give away. Ask yourself, "Is getting rid of a little stress worth $10,000?" 3% If your need to be liked or seen as a reasonable person is urging you to make a concession, forget about it. The other side is more likely to view you as a chump or an easy mark if you concede too readily. Remember, too, that deal making isn't about making friends. 4. The Ticking Clock In a buyer-seller negotiation, such as the Jake and Carla example, time can be an important tool. From the buyer's perspective, the seller should never be allowed to feel that he can indefinitely sit on the buyer's most recent bid while he awaits a better offer. The seller will simply use the offer to improve his BATNA. The remedy is to attach an expiration date to the offer to buy. Negotiators sometimes refer to this tactic as an exploding offer. If Carla decided to counter Jake's latest offer ($385,000) with a bid of $360,000, she might stipulate that "this offer is good until 9PM on this coming Saturday, September 23." That expiration date would put a fire under Jake and force him to make a decision. In the absence of an expiration date, Jake would simply tell himself, "Now that I have an option to sell at $360,000, I can wait for a better offer." 5. Package Options for a Favorable Deal Offering alternative proposals (two or more) is often an effective deal-making tactic. Consider this example: Joe is negotiating with Robert and Sharon for the purchase of their small sailboat and trailer. The trailer is of minimal importance to Joe because he expects to secure a permanent mooring. But it wouldn't be a bad thing to own, as he may have to tow the boat some day. So, he makes alternative proposals: "I'm willing to pay $18,000 for the boat and trailer as a package, or $16,000 for the boat alone. You could sell the trailer separately. What's your preference?" Package options have dual benefits. First, people don't like to feel pushed into a corner. A single proposal may feel like an ultimatum - take it or leave it. But when presented with alternative proposals, people may compare the proposals to each other instead of to their original goals. In addition, when the other negotiators won't discuss their interests, you can often infer them by noticing which proposal they prefer. Before presenting alternative proposals, however, do the following: 1. Assess the value of each option to each side. 2. Consider whether the diminution of one option would be offset by an enhancement of another. 3. If you prefer one of the alternatives, adjust at least one of the proposals so that you feel equally positive about at least two of them. 6. Closing the Deal Assuming that things go well, you'll eventually reach a point where you're fairly satisfied with the negotiation and you want to wrap things up. The other side may or may not be at the same point. Here are four recommended steps for closing the deal: 6.1. Signal the end of the road before you get there. If you have been negotiating back and forth, showing flexibility on various issues, and then suddenly announce you're at your bottom line, you are likely to be challenged or not taken seriously. So, as you approach the parameters of what you would like in a final deal, say so. Repeat the warning, not as a threat but as a courtesy, particularly if the other negotiator seems to expect a lot more movement in his or her direction. 6.2. Allow flexibility if you anticipate going beyond the final round. If you are aware that the other negotiator lacks final authority, leave yourself some flexibility, or wiggle room, in the final terms. More specifically, don't give the other side your best and last offer - save that in case you have to bend during the final round. However: A. Don't create so much flexibility that the deal will be rejected by the other side's decision maker. B. Consider whatever final trade you would be willing to make if you end up requesting significant adjustment in the final terms. 6.3. Discourage the other side from seeking further concessions. If you appear to have reached a final deal that is acceptable to the other side (and perhaps also favorable to you), discourage further tweaking in their favor: % Express your willingness to accept the total package, without changes. % Explain that adjustment in their favor on one term would have to be balanced by adjustment in your favor on another. For example, "If we open that issue, then I'm afraid we'll have to reopen the whole deal for it to work for me." 6.4. Write down the terms. If your negotiation time has been well spent, don't risk ruining it by failing to record and sign your agreement. People's memories of their agreement will inevitably diverge; recording the terms of the agreement avoids future disputes and confusion. It also provides closure. Even if counsel will draft the official documents, write an informal agreement in principle. Decide whether it is binding or not, and say so in the document. Even if your informal agreement is nonbinding, it will serve as a common reference by both parties as future, good-faith questions arise.Tactics for Integrative Negotiations

Getting Started Here also we begin by learning about other side's concerns and interests. Don't make a proposal too quickly; a premature offer won't benefit from information gleaned during the negotiation process itself. Instead of hastily throwing out an offer, try these techniques: 1. Ask open-ended questions about the other side's needs, interests, concerns, and goals. 2. Probe the other side's willingness to trade off one thing for another. For example, "Do you care more about X or Y?" 3. Inquire about the other side's underlying interests by asking why certain conditions - for example, a particular delivery date - are important. 4. Listen closely to the other side's responses without jumping in to cross-examine, correct, or object. 5. Be an active listener. The more they talk, the more information you're likely to get. 6. Express empathy for the other side's perspective, needs, and interest. Empathy is especially important in highly charged situations. It takes active listening one step further, confirming that you can connect with the speak and the underlying tensions or emotional issues. 7. Adjust your assumptions based on what you've learned. The assumptions that you've make about the other side's interests and circumstances when preparing for the negotiation may be wrong, in which case you'll need to revisit your strategy. 8. Be forthcoming about your own business needs, interests, and concerns. It is just as important to assert what you need and want (and why) as it is to listen carefully to the other side. Indeed, striking a balance between empathy and assertiveness is essential to effective negotiating. If you are too empathetic and insufficiently assertive, you may shortchange your own interests. If you are too assertive and insufficiently empathetic, you risk missing a deal and escalating emotions. But don't barrage the other side with all of your interests and concerns at once. 9. Work to create a two-way exchange of information. Stay flexible about who asks questions and who states concerns first. If the other side seems uncomfortable with your initial questions, offer to talk about one or two of your most important points - and explain why they are important. 10. Continue your relationship-building efforts even after the negotiating has begun. Show empathy, respect, and courtesy throughout the proceedings. Always remember that the other side consists of human beings with feelings, limits, and vulnerabilities. 11. Refrain from personal attacks. Don't accuse or blame. Maintain a sense of humor. 12. When an issue seems to make another negotiator tense, acknowledge the thorniness of the issue. 13. Don't feel pressured to close a deal too quickly. Instead, generate options that offer mutual gain. Tips for Active Listening There's a big difference between keeping your mouth shut while the other party is talking and what communication experts refer to as "active" listening. Active listening helps you capture what the other side has to say while signaling that you are alert and eager to hear what the other side has on its mind. Here are some tips for being an active listener. They will help you in any type of negotiation. 1. Keep your eyes on the speaker. 2. Take notes as appropriate. 3. Don't allow yourself to think about anything but what the speaker has saying. 4. Resist the urge to formulate your response until after the speaker has finished. 5. Pay attention to the speaker's body language. 6. Ask questions to get more information and to encourage the speaker to continue. 7. Repeat in your own words what you've heard to ensure that you understand and to let the speaker know that you've processed his or her words. 1. Look for Options That Exploit Differences During the negotiation, you are confronted with the other side's positions and come to understand the interests underlying those positions. It is hoped that the other side will understand your positions. It is hoped that the other side will understand your positions and interests just as well. The challenge now is to arrive at an outcome that satisfies both parties' interests. One place to look for a mutually satisfying outcome is in the differences between the parties. People know intuitively to build upon their shared interests. Less obvious sources of value are in the differences between them. By trading on differences, you create value that neither party could have created on its own. In particular, look for differences in these places: 1. Access to resources. For example, Martha, who owns both a retail store and a restaurant, is negotiating with an interior designer for his services in renovating the restaurant. She agrees to pay a somewhat higher price than planned for the restaurant design in exchange for the designer ordering fixtures and furnishings for the retail store at his trade discount. The owner would not otherwise have ready access to these discounts - yet providing them costs the designer nothing. Value has been created for both sides. 2. Future expectations. For example, the current owner of a business is selling. He demands a high price because he predicts that the market for his will increase over time. The potential buyer is unwilling to pay that high price; she does not share the owner's rosy outlook. Within this difference of opinion, they see an opportunity. They agree to a base sale price, plus 20 percent of the company's increased revenues over the next five years - if any - with the current owner providing advice and assisting with marketing and distribution plans over that period. Under this arrangement, the buyer will get a lower price and the seller will be able to capture the upside growth in the business he anticipates. 3. Time preference. The timing of a deal can be a barrier to a mutually satisfactory conclusion. For example, Jonathan is happy with the CEO's plan to promote him to vice president of marketing, but unhappy that he must play a waiting role until the incumbent retires six months hence. The CEO, however, has arranged for the current marketing VP to use that time to finalize the company's strategic distribution agreement with its dealers. "He engineered this strategy and has close personal ties to key players on the other side. I want him to conclude the deal." Within these differences, however, the CEO finds a solution: He will put Jonathan in charge of a team that is working on the plan to implement the new distribution contract. That satisfies Jonathan and benefits the company. 4. Risk aversion. What is highly risky for one party is often less risky for another. Parties often have different risk tolerances. In these cases, value can be created by shifting risk to the party better able to bear it - in exchange, of course, for higher potential returns for the party assuming the risk. For example, Jeff and Jessica are negotiating with Jones Properties, a developer, for the purchase of a newly built condominium. For Jeff and Jessica, newcomers to the housing market, the condo would be by far their largest investment. "What if I got transferred and had to sell sometime soon?" Jeff ponders. "If the condo market were depressed at the time of sale, we'd take a heavy loss." Jones Properties, on the other hand, owns hundreds of properties in dozens of buildings scattered around the country. Its risk of ownership is highly diversified. And so, it posed a solution: As part of the sales agreement, it will agree to buy back Jeff and Jessica's condo at any time within two years of purchase at 95 percent of the purchase price less transaction costs. Take Your Time Few more suggestions for generating integrative solutions: 1. Move from a particular issue to a more general description of the problem, then to theoretical solutions, and finally back to the specific issue. 2. Pay special attention to shared interests and opportunities for cooperation. 3. Consider joint brainstorming with the other side - it can be a very fruitful way of generating creative alternatives. Set ground rules that encourage the participants to express any and all ideas, no matter how wild or impractical. Be careful not to criticize or express disapproval of any suggestion. At this stage, such judgements inhibit creativity, making people reluctant to make further suggestions - and more likely to criticize any idea you volunteer as well.General Tactics: Framing and Continual Evaluation

Whether you're engaged in a distributive or integrative negotiation, your results will be better if you adopt any one of the three following tactics: 1. Framing 2. Process moves 3. Continual evaluation These tactics may be used at or away from the table. Process moves were discussed in chapter 3, so this section focuses on the other two tactics.Framing

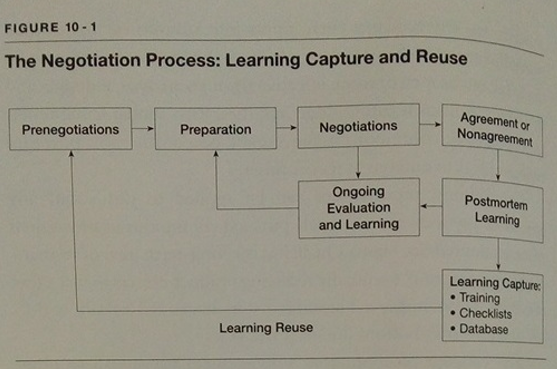

Fill a glass of water halfway to the top. Now, if you describe this glass to someone else, would you say it was half empty or half full? Whichever way you describe the glass, you are framing the situation. If the other person accepts that frame without question, subsequent discussion will proceed within that frame. This could be advantageous to you. Consider these examples. 1. The glass is half empty. A labor negotiator tries to frame upcoming wage and benefit talks with a company. "During the past three years, hard work by our members has helped this company to triple its revenues and almost double its profits. Management salaries have grown substantially as a result, and key executives have rewarded themselves with record-breaking bonuses. And what is management willing to share with rank-and-file employees? A mere 25 percent increase in wages over the next three years! That, we contend, is a slap in the face to the people who have created this company's good fortunes." In other words, a fair sharing of the wealth created by the employees should frame negotiations. 2. The glass is half full. Management makes its pitch to labor. "We are pleased to offer our rank-and-file employees a salary increments of 25 percent over the next three years. That increase is one-third higher than what our main market competitors have offered their employees. It will put the average annual wage of our people some $3,000 above the industry average and will allow the company to retain sufficient funds to reinvest in the technology it needs to ensure job security and future wage increases." In other words, wage negotiations should be made with a frame that emphasizes financial constraints and the company's desire to ensure job security and higher future incomes. ~ ~ ~ Marjorie Corman Aaron, a consultant and trainer with many years of experience in mediation, negotiation, and dispute resolution, gives the example of a bank officer faced with demands by local community activists to provide more generous lending arrangements. In advising the bank's board on a course of action, the officer could adopt any one of several frames: He could frame the demands to the board of directors as a "shakedown," thereby invoking a mental model that resists "knuckling under to pressure". But if he framed it as a business problem - the need to earn the goodwill of the community - the board might be persuaded to fund some programs. If he framed the bank's circumstances as "wrestling with a 500-pound gorilla", the board would probably do whatever it would take to get the gorilla off its back, and quickly. So, if you frame your position in terms of a mental model the other side can embrace, you'll have less trouble moving toward agreement. More generally, you can use these frames: 1. Frame your proposal in terms that represent a gain instead of a loss. Instead of saying "My current offer is only 10 percent less than what you are asking," say "I've already increased my offer by 10 percent." 2. Tap into people's natural aversion to risk. Risk aversion has two consequences: 2.a. People who are very risk averse will often accept larger potential losses in the future rather than incur smaller losses today. This explains why many people will seek remedies in court and possible suffer paying a larger settlement in the future rather than pay a smaller settlement today. 2.b. Most people prefer a bird in the hand rather than two in the bush. In other words, they prefer the certainty of a smaller offer to the uncertainty of a larger future gain. "I know that you want $400,000 for that property, and you may get it someday. However, I'm willing to pay $340,000 for it today. Can we make a deal?" Continual Evaluation and Preparation Normally we think of negotiating as linear process of preparation, negotiation, and eventual agreement or failure. The first step takes place away from the table; the rest take place at the table. In simple interactions, this model often holds true. But many other negotiations are complex and can take place in succeeding rounds and involve several different parties. New information can appear at various points, casting new light on the issues at stake. Different parties can offer concessions or heighten their demands. This more complex dynamic suggests a nonlinear approach to the preparation process, as shown in figure 4-1. Here preparation is followed by negotiation, which produces outcomes and information that require evaluation. The outputs of evaluation then feed into a new round of preparation and subsequent negotiation. Round and round it goes until agreement is reached or the parties call it quits. Michael Watkins, author and expert on the subject of negotiations, suggests that the ambiguities and uncertainties associated with complex deals should caution negotiators to give less attention to pre-negotiation preparation and more attention to what he calls "planning to learn". Learning must be ongoing. After all, the information available to negotiators before going to the table is bound to be limited and may even be inaccurate. So instead of setting your course based on pre-negotiation information, consider doing the following: 1. Take small steps, gathering better information as you proceed. 2. Continually learn from new information and the behavior of the other side. 3. Use that learning to adjust and readjust your course as you move forward. Evaluation is another important element of the process and should be part of your tactics. Periodically, you should put a little distance between yourself and the negotiations and ask: How are things going? Are negotiations proceeding along a track that will eventually serve my goals? Are they playing my game, or am I playing theirs? Whose frame dominates the talks? If I were representing the other side, how would I answer these same questions? Answering these questions objectively isn't natural or easy. A person must take the perspective of a neutral stranger and adopt an outside-looking-in stance. This is essential to mastering the game. Summing Up The first challenge in negotiation is to get the other side to the table. This won't happen unless the other side sees that it is better off negotiating than going with the status quo. Encourage negotiation by offering incentives, making the status quo expensive, and by enlisting the help of allies. Once you've gotten the other side to the table, get things off to a good start by relieving tension, making sure that all parties agree with the agenda and the process, and setting the right tone. Several tactics are particularly useful in distributed (or win-lose) deals: 1. Establish an anchor, an initial position around which negotiations make adjustments. 2. If an initial anchor is unacceptable to you, steer the conversation away from numbers and proposals. Focus instead on interests, concerns and generalities. Then, after some time has passed and more information has surfaced, put your number or proposal on the table, and support it with sound reasoning. 3. Make concessionary moves if you must. But remember, many interpret a large concessionary move as an indicator that you're capable of conceding still more. A small concession, on the other hand, is generally seen as an indication that the bidding is approaching the reservation price and that any succeeding concessions will be smaller and smaller. Tactics for distributive (win-win) negotiations are fundamentally different from those just described since value creation is one of the goals. So, concentrate on these tactics: 1. Active listening 2. Exploiting complementary interests 3. Packaging options for more favorable deals Finally, the chapter offered tactics useable in any context: 1. Framing 2. Continual evaluationCHAPTER 5: FREQUENTLY ASKED TACTICAL QUESTIONS

FAQs About Price Q1. Should I ever state my acceptable range? A1: Some negotiators will ask you to state a monetary range of what you're willing to pay. Do not comply. This would give away your reservation price. For example, if you tell someone that you would pay $20,000 to $25,000 for piece of property, rest assured that you will pay at least $25,000. The other side will think, "That's the reservation price," and it is the only number he or she will pay attention to. It is much better to work in terms of your bottom line, or "the best I can do." The only reason to mention a range occurs toward the end of the negotiating process, to discourage the other side from pushing you beyond it. For example, after several rounds of back and forth on a dollar figure, you are at $23,000, and the other side is at $30,000 and seems to be pushing for a deal at $28,000. You could say, "My range walking in here today was $20,000 to $23,000, but not above $25,000." Revealing your range may make it easier for the seller to accept $25,000 because he will feel that he has pushed you to the top. Q2: Should I ever tell the other side my real bottom line? A2: You can reveal your bottom line, but only if you've reached it (or are about to). If you do reveal your bottom line, make sure you call it just that, with appropriate emphasis or firmness. Otherwise, the other side may not take you seriously, and may view that number or proposal as just another step on the way to a final deal. Q3: Suppose that the other side opens with an incredibly unreasonable number. Should I counter with an equally unreasonable number, or decline to counter at all? A3: Consider one of the following strategies: 1. Make a joke to indicate that you don't consider the other side's number a serious offer: "Right, and the moon is made of green cheese. Now, let's get serious." 2. Clearly state that the other side's number is entirely out of the range you had imagined for the deal. Go back to talking about interests. Ask about a specific issue for some importance. Explain your perspective on the deal - how it might have value to you, or others similarly situated. (You will, of course, be describing value that falls in entirely different ballpark.) Let some time and discussion go by. Then you might suggest a number or proposal that you can justify as reasonable and that is in the favorable end of your range (or close to what you estimate their reservation price is, whichever is better). Do not refer to their initial number or proposal. Ignore it. If you counter with an equally unreasonable number, you will either contribute to the impasse or make the road to agreement longer and more difficult. 3. Indicate that the offer is entirely out of range. Then express your concern that a deal may not be possible. Try to get the other side to bid against itself as follows: "That offer is so low that, we will not even consider it. Why don't you confer with people and get back to me with something more realistic? I'll be in my office all afternoon." FAQs About Process Q1. Is it ever acceptable to bid against myself-to make two moves in a row? A1: It's not a good idea. Just say, "Wait, you seem to be asking me to make another move here. I made the last offer; I don't want to bid against myself. Give me your offer." This usually elicits at least a token move on the other side. If it doesn't, if they are stuck and the only way to make progress is for you to move again, you should announce your awareness of what you are doing, and state that it should not be considered a precedent. Make your next move in good faith, to a proposal or number you can justify as reasonable, explain your reasoning, and ask the other side to do the same. If they don't, you may have reached an impasse. To bridge the gap, consider broadening the discussion of the parties' interests, and formulating other creative options, perhaps through joint brainstorming. You might bring in a third-party facilitator. Q2. Is it smart or fair to bluff? A2: Is it okay to bluff or puff during a negotiation? Sure. One man's puff is another's positive spin. One woman's bluff is another's best foot forward. Lying about material fact, however, is almost certainly grounds for legal action. In certain circumstances, creating a false impression or failing to disclose material information may be a formal legal breach. Nevertheless, as long as what you bring to the table has real value, you need not real all the circumstances that make you willing to conclude a deal. Thus, if you are negotiating the terms of a job offer, there is nothing wrong with describing the major projects for which you have been responsible and your likely next step on the corporate ladder in your current company. There is no shame in describing your achievements in a positive light. You need not mention that the new division president is impossible to deal with. Q3: In a complex deal, is it better to reach agreement issue by issue or wait until the end? A3: Every deal is different, but it's generally better to aim for tentative agreements, or agreed-upon ranges, for each issue, one at a time. This will give you the necessary flexibility to make value-creating trade-offs between issues later on and to create alternative packages of different options. The risk of negotiating each issue in serial fashion is that you lose opportunities to create value through trades. Q4: Is it better to deal with difficult or easy issues first? A4: In general, dealing with easier issues will build momentum, deepen the parties' commitment to the process, and enable the parties to become familiar with each other's negotiation and communication styles before hitting the tough stuff. In some instances, however, you may want to deal with a more difficult issue as a threshold matter. If you cannot reach tentative agreement on the difficult issues, then you will not have wasted time on the smaller issues. It is also true that once the most difficult issue is resolved, smaller issues often fall more easily into place. Q5: What if there is an unexpected turn in the road - before or after an agreement? A5: Unexpected developments can endanger potential agreements. They can also undermine agreements already made. Consider this example: You have entered a fixed price contract with a general contractor to build new office suites and conference rooms in an older brick building purchased by your company. The suites and conference rooms are to be paneled in a lovely pear wood. But after the contract is signed, a pear wood blight is discovered, which triples the cost of pear wood. Under your negotiated agreement, the contractor is to bear the risk of fluctuation in material costs. If you insist on that term, the contractor may try to make up some of the cost in other ways, perhaps by shorting the detail work. If you agree to renegotiate, absorbing some or all of the additional cost (or choosing a different wood), the contractor is more likely to do a high-quality job. The next month, you discover that the bottom floor of the building is sinking, and walls are cracking because of settling in the foundation. This was not part of the original contract, but you want the contractor to take it on as soon as possible and at a reasonable price. What goes around comes around. Similar events can happen while you're in the process of negotiating a deal. In both cases, analyze how the unexpected development affects the decision to go forward. Determine if a deal still makes sense, or if you need to undo the deal that has been negotiated. Also: 1. Contact the negotiators on the other side immediately. 2. Acknowledge the unexpected nature of what has happened. 3. Affirm your commitment to working on the problem (if that is so). 4. Jointly discuss the underlying principles and intent of the deal as originally negotiated and agree upon what issues or provisions are affected. 5. Pick up the negotiations again. FAQs About People Problems Q1: What happens when you pit a collaborative negotiator against a positional hard bargainer? A1: A positional bargainer aims to win at the other side's expense. He will agree that "compromise is what will get us to a deal," then expect all the compromises to come from the other side. An effective collaborative negotiator should be able to deal with this type of negotiator if she recognizes the situation for what it is. After all, she will have analyzed her BATNA, set a reservation price, and considered both opening and first-offer strategies. If the positional hard bargainer refuses to disclose information and begins to use any disclosures against the cooperative bargainer, that's a clear signal that this is not likely to be a win-win proposition. The negotiator should seek reciprocity or refrain from providing additional information. The real question is whether the collaborative negotiator will be able to "convert" the hard bargainer, at least sufficiently to create some value in the deal. The answer is "maybe". If the collaborative negotiator is effective and resourceful, she should be able to tease out some of the interests underlying the hard bargainer's positions. She may then suggest different options and packages for meeting both parties' interests. Even the most recalcitrant hard bargainer can recognize when it benefits his interests to join in creating value. Q2: How should I respond if the other side seeks to change something in its offer after a deal has been reached? A2: Chances are the other side afflicted with the "winner's curse": Whenever they reach a deal, they are cursed with the thought that they could have gotten more. If the other side tries to change one item, express surprise or disappointment. Explain that if they must make a change, then they must understand that you will want to open up other issues as well. "I agreed to a total package. A change on one issue affects the entire package. Are you willing to renegotiate other issues?" If the answer is yes, then the other side was sincere, and you should proceed with the renegotiation. If they reconsider and withdraw the request for a change, then assume that they were just testing you. If they insist that they must have this change and no others, express dismay, then decide whether the adjusted deal has sufficient value for you to agree. Q3: What should I do when the negotiator on the other side has a temper tantrum? A3: Don't respond in kind. Instead, help him regain control. The right response will depend upon how angry or upset you fell, the value of the deal, and whether it is your choice to proceed. Here are some alternatives: % Sit quietly. Say nothing. After a few moments, resume the negotiation with a calm voice. % Stop. Say, "This is getting us nowhere. I'm inclined to leave and let you cool off. Is that what you want?" If his shouting was intended to get you upset and off-balance, you certainly shouldn't reward that strategy by negotiating in that less-than-top-form condition. Also, keep in mind that you have some control over who you will deal with. Consider contacting someone else on the other side to suggest that another negotiator be assigned to the deal. Q4: I don't believe what the other side is saying. What should I do? A4: You suspect the other side is lying or bluffing. At best, they are just telling you what they think is needed for an agreement and have no intention of following through on their promises. Here's how you could respond: 1. Make sure they understand that deal is predicated on their accurate and truthful representation of the situation. For example: "If you can't provide shipping on the schedule we've described, it's best to tell me right now." 2. Require that they provide back-up documentation, and that the deal be explicitly contingent on its accuracy. 3. Insist on enforcement mechanisms, such as a penalty for non-compliance (or perhaps positive incentives for early performance). Example: "We expect the final agreement to contain a late fee of $1,000 per day for every day that construction milestones are not met. On the other hand, we are willing to pay you a bonus of $20,000 if you can have the building ready for occupancy on or before July 20 of the coming year." Q5: When, if ever, is it appropriate to negotiate over the telephone or by email? Or is it essential to insist on a face-to-face meeting? A5: It is far better to negotiate face to face when personal, nonverbal cues matter. For example, is this a deal in which the other side might be tempted to lie or shade the truth? Are the parties professionally or emotionally invested in what's at stake? These situations often reveal themselves through nonverbal cues. Some research indicates that people are less likely to lie in person, perhaps because they fear that the other side will detect their deception. Indeed, in a face-to-face negotiation we see the sideways glances of the other negotiating team, we sense when they are becoming uncomfortable, and we pick up the nonverbal cues that indicate something is more important than their words indicate. Anecdotal evidence indicates that email or other written messages may have a greater tendency to result in disputes and impasses. The person who receives an email or fax may interpret a comment negatively when the sender did not intend it that way. Because the sender is not there to read the facial expression or hear the exclamation of the recipient, he or she can't correct the impression. The original sender is surprised and feels unjustifiably attacked when the return message carries a nasty tone and responds in kind. On the other hand, email communication is devoid of emotions. For an inexperienced negotiator, this can be a big plus. He or she is less likely to emotionally whipsawed by an aggressive negotiator on the other side. And since email makes it possible to reflect on a message before hitting the "Send" button, one is less likely to give away vital information to the other side. Unwarranted disclosure can be a problem in face-to-face discussions. Some people talk too much. Either through thoughtlessness or an effort to make themselves seem important, they give away vital information. The chance of doing this is lessened when email is the medium of communication. Some, but not all, of these problems of email are partially solved by using the telephone. You can use and interpret tone of voice of keep communications on track. However, it is more cumbersome to propose creative ideas. You can't put them on a chalkboard or easel. And some recent research indicates that people are more likely to bluff over the telephone. On the other hand, if the negotiation is over a simple issue, where personal communication is not likely to matter, the most efficient method works best. Q6: How should I react when the other side challenges my credentials, status, or authority to make a deal? A6: Why are they challenging you? Are they just trying to make you defensive, put you off-balance? Or do they have genuine concerns? The best approach is to shift the discussion to general ground rules. Say something like this: "Right. We should be clear about whose approval is needed for a deal - both on my side and yours. I am authorized to complete the deal with these parameters: x, y and z. I need formal approval for any agreements outside those parameters. Now, what about you? What are you authorized to do?" If the challenge to your authority was posed to make you feel defensive, you will have demonstrated that such strategies will not be successful.CHAPTER 6: BARRIERS TO AGREEMENT. HOW TO RECOGNIZE AND OVERCOME THEM.