Book by Daniel Shapiro: Negotiating the Nonnegotiable. How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts (2016)

Section 1: The Tribes Effect

Ch 1: The Hidden Power of Identity

The world exploded at Davos. It happened several years ago at the World Economic Forum's annual summit in the snow-capped mountains of Switzerland. I had convened a meeting of forty-five world leaders in a small room tucked away from the eyes and ears of the reporting press. These leaders had negotiated some of the world's most challenging conflicts, but none were prepared for what would happen next—a negotiation of the strangest kind that would reach beyond the halls of that summit to the epicenter of all our lives.

It all started innocently enough. As the leaders streamed into the room, a young staffer handed each of them a colored scarf and escorted them to one of six tables. I watched as the CEO of a Fortune 50 company made his way to his seat, followed by a deputy head of state, who greeted the CEO with a diplomatic nod. A prominent university president settled next to a security expert, while at a neighboring table an artist chatted with a professor. Soft music played in the background, and the mood was light.

As the clock struck one, the music quieted and I stepped to the center of the room. “Welcome,” I said a bit nervously, taking stock of this esteemed group, who looked at me in anticipation. “It is an honor to be here with all of you today.”

As the word “tribes” appeared on a screen behind me, I launched into the session. “Our world is becoming more and more of a tribal world. As global interdependence and advances in technology intertwine, we have more opportunity to connect with more people. Yet this very thread of connection—this emerging global community—also threatens fundamental aspects of who we are. It is only natural, then, that we tend to withdraw to the security and continuity of tribes.”The group appeared intrigued. I continued. “We all belong to multiple tribes. A tribe is any group to which we see ourselves as similar in kind, whether based on religion or ethnicity or even our place of work. We feel a kinlike connection to the tribe; we emotionally invest in it. This means a religious community or nation can feel like a tribe. A family can be so tightly knit that it feels like a tribe. Even multinational corporations can take on the feel of a tribe. Tribes are all around us.

“Today we'll be exploring the power of tribes. You and the others at your table will have the opportunity to get to know one another—by forming a tribe of your own at your table. You'll have fifty minutes to answer a small set of challenging questions to define the key qualities of your tribe. Please answer all these questions through consensus, not voting.

And be sure to remain true to your own belief system.”

The instructions seemed acceptable to everyone—until I passed out the worksheet containing the questions. The professor's hand darted into the air. “You want us to answer these questions through consensus? In fifty minutes? Come on!”

He was justifiably aggravated, as the participants were being asked to answer such morally divisive questions as “Does your tribe believe in capital punishment?,” “Does your tribe believe in abortion?,” and “What are the three most important values of your tribe?”

“I've facilitated this exercise dozens of times,” I assured the professor,

“and everyone is always somehow able to finish. So just give it your best shot, and be sure to have a response to each question by the end of the allotted time.” He nodded begrudgingly, and the participants set to work.

One tribe spent nearly thirty minutes defining and prioritizing its tribal values, while another got stuck on whether capital punishment should be legal. A tribe in a far corner laughed and joked like friends at a bar while a neighboring table became deeply absorbed in the task.

At the fifty-minute mark, the room went pitch-black. Ominous music began to play—a pipe organ droned a haunting scale of notes. “What's going on?” whispered an eighty-five-year-old venture capitalist. His head swung around as he heard a loud knock on a side door, then a loud bang. Everyone in the room went still, unsure what to expect. In barged a wide-eyed alien with pale green skin and flylike black eyes. It weaved through the tables, passing the gaping venture capitalist, and slowed to rake the professor's hair with its long green tentacles. “You measly earthlings,” the alien growled. “I have come to destroy the Earth! “I will give you one opportunity to save this world from complete destruction,” taunted the alien. “You must choose one of these six tribes as the tribe for everyone here. All of you must take on the attributes of that one tribe. You cannot change any of that tribe's attributes. And if you cannot come to full agreement by the end of three rounds of negotiation,” the alien snarled, “the world will be destrrroyyyyyed!” The creature then raised its arms wide, shrieked with laughter, and left the room.

•••

The lights came back on, and everyone looked around, bewildered. There were a few chuckles, and then the participants sprang into action, huddling at their tables to define their strategy for the upcoming negotiations.

Six barstools stood in the middle of the room, one for a delegate from each tribe. I announced the advent of round one, and the tribes sent their representatives to negotiate. This round was fairly amicable. The six tribes familiarized themselves with one another's key characteristics.

After a few minutes, the CEO of a Dubai-based company said, “We must start by talking about our negotiation process. How are we going to make our decision here?” It was a good, rational question, the kind that virtually any negotiation consultant would advise should be raised. But the CEO was drowned out by a magazine editor from the Happy Tribe, who, feeling pressure to advocate for his own group, complained, “Why is no one listening to our tribe?”

“You'll get your chance,” replied a representative from the Cosmopolitan Tribe. But round one ended before the magazine editor could say another word.

In round two, the emotional temperature of the room intensified.

These leaders were determined to save the world. The charismatic delegate for the Rainbow Tribe, a sharply dressed business executive, proclaimed,

“We believe in all colors, all genders, all ethnicities. Come to our tribe! We will accept you all!” He spread his arms in a welcoming gesture, and two tribes immediately joined with him. A venture capitalist crossed his arms, glared at the Rainbow Tribe delegate, and complained, “If we are all equal, why don't you join our tribe?”

In round three, a frenzy overtook the room. The delegates for this round included five men and one woman, all of whom argued about whether humanitarianism or compassion represented a more important core value. The men yelled over one another and over the woman, who became so enraged that she stood on her stool, her face flushed, and pointed her finger and shouted, “This is just another example of male competitive behavior! You all come to my tribe!” Only one tribe agreed to join hers.

Moments later the world exploded.

The Fundamental Force of Conflict

* The Tribes Exercise evokes emotional dynamics intrinsic to real-world conflict.

* It is hard to notice these dynamics when caught in them.

Key Dimensions of Conflict Resolution

This book provides crucial advice to resolve emotionally charged conflicts.

The world could have been saved at Davos if the leaders had addressed the key dimensions of conflict resolution: rationality, emotions, and identity.

While scholars often treat these dimensions as independent, neuroscience suggests they interrelate. Only by addressing all three can we hope to arrive at a satisfying resolution to an emotionally charged conflict.

Unlocking the Power of Identity

This book reveals a powerful method to navigate the complex landscape of identity. You can know facts with certainty, but you can never fully know yourself. The closest you can get is through reflection. The more you reflect, the more you know. So as you read this book, think about the role of identity in your toughest conflicts. You will come to see hidden forces fueling destructive relations, as well as new possibilities for resolution. At Davos, the leaders stumbled through this process. After the world exploded, they fell silent. I asked, “How are you feeling?” They all looked depressed, save one: the professor. He stood, his face red, and pointed his finger at me. “This is your fault!” he shouted. “You set us up to have the world explode—with all your questions we had to answer, with the short time frame you enforced.” He shook his head, repeating, “This is all your fault.” He sat down, crossed his arms, and glared at me.

I had expected that someone in the group might blame me in the event that the world exploded. I was an easy target—in many ways a fair target— but the professor's anger was more intense than I had anticipated. All eyes turned toward me.

“You're right,” I said. “I did anything and everything in my power to structure this exercise so that the world would explode. I gave you virtually impossible questions to agree upon. I gave you limited time to negotiate. I had the alien force you to choose one tribe over the others. So yes, you're right.”

The professor's face softened as I acknowledged my responsibility.

His arms uncrossed.

“But,” I continued, slowing the pace of my words, “at the end of the day, you had a choice. You could have come to agreement. You could have questioned me and resisted the rules. You could have. But you didn't.

You. . . had . . . a choice.”

The professor nodded, his cheeks flushed. I had revealed the truth he did not want to face: He and the other leaders had possessed full power to save the world, but had failed to do so. They had locked themselves into a narrow definition of identity and let the world go down in flames. The conflict had never been immutable, even if it had felt that way.

Ch 2: The Dual Nature of Identity

In Lewis Carroll's whimsical Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, charming young Alice encounters an enigmatic, hookah-smoking caterpillar, who asks her a seemingly simple question: “Who are YOU?”

Alice hesitantly replies, “I—I hardly know, Sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

Alice stumbles around tricky questions of identity. Who is she, how did she become who she is, and how does she even know she is who she thinks she is? Her musing that she must have changed several times since the morning indicates her conviction that identity is fluid. But what troubles poor Alice is that, despite this belief, she feels a consistency in her lived experience. She knows she has changed but feels the same.

This paradox cuts right to the heart of conflict resolution. If identity is absolutely fixed, then the only way to resolve a conflict is to compromise your own identity or persuade the other side to compromise theirs. Conflict thus becomes a win-lose proposition. Yet if your identity is entirely fluid, you have no assurance that either party will honor an agreement. How can you be held accountable for your actions of yesterday if you are a changed person today?

A Way Out

Alice gets us out of this conundrum with an insight that proves essential for conflict resolution: Some aspects of her identity change—while others remain the same. Her identity is both fluid and fixed. In a conflict, however, it is easy to lose sight of this fact. When your identity is threatened, you hunker down in self-defense and conceive of it as a single, immutable whole. I call this the fixed-identity fallacy—and because of it, you demand the other party acquiesce to your perspectives, your sense of right and wrong, your values. If the other side holds this same egoistic assumption, both of you get stuck in an ever-escalating impasse, until your conflict feels intractable.

But this is an illusion. To assume from the outset that your conflict is insoluble is to bury the possibility of reconciliation deep in the ground.

While an emotionally charged conflict is hard to resolve, it is much more useful to direct attention toward those aspects of identity that you can affect rather than those that appear immutable. In fact, virtually all parts of your identity have a degree of fluidity, though some are much easier to change than others.

This chapter lays the groundwork for the remainder of the book, providing you with foundational tools to overcome the fixed-identity fallacy. Despite the pervasive impact of identity, disputants seldom know what it is or how to address it. Thus this chapter presents a framework to help you discover and leverage the most deeply significant aspects of identity underpinning your conflict.

What Is Identity?

Your identity comprises the full spectrum of persistent and fleeting characteristics that define you. These characteristics integrate to make you one: a unified whole that includes your body and mind, your neurological apparatus and position in society, your unconscious processes and conscious thoughts, and your enduring sense of existence as well as your passing observations.

Though these characteristics define you, you also define them. You are as much the object of analysis as the subject doing the analysis. This reciprocal relationship is vividly illustrated by M. C. Escher's sketch Drawing Hands, which depicts the hands of an artist drawing themselves.

When I asked my then-six-year-old son, Zachary, for his thoughts on this picture, he said, “He's making himself!” When it comes to identity, you make yourself too.

Core Identity: The Biography of Your Being

Your core identity is the spectrum of characteristics that define you as an individual or as a group. It includes everything from your body, personality, and occupation to your spiritual beliefs and cultural practices. The world would spin into chaos if no one had a core identity. Nations would have no constitutions or flags; businesses would have no brands; and people would have no names or personalities. Your core identity is the platform from which you synthesize your experiences into a coherent sense of self with both continuity and clear ideals. Should you feel confused about your core identity—unsure of who you are or what you stand for—decisions of all kinds become problematic.

The multiplicity of identity.

Your core identity includes your personal preferences and personality traits as well as your identification with social groups. Do you see yourself as American, Japanese, Lebanese,

Hispanic, Protestant, Muslim, Jewish, Hindi, or atheist? As a student, parent, executive, liberal, or conservative? Because you belong to multiple groups, you have multiple social identities. A person may be Chinese American, Protestant, a teacher, and conservative.

In a conflict, you must decide which of your social identities to prioritize. You may feel competing loyalties based on your faith, ethnicity, political convictions, and national citizenship. Perhaps your religious identity feels most important to you, but you emphasize your national identity to fit in with your neighbors. Even in casual conversation with a friend, you must decide whether to discuss politics, religion, or work responsibilities, with each decision shaping the contours of your identity.

Just as you identify yourself as a member of specific groups, others pigeonhole you. If you are the only Chinese American executive at your company's meeting on cultural diversity, colleagues may make you feel very aware of that identity, whereas it may fall out of your awareness while you meet with a good friend at a café. But you are not powerless to social labeling—a lesson that Professor Henri Tajfel, founder of social identity theory, learned during World War II. He was a Polish Jew who studied in France and joined the French army during the war. A year into his service, the German army captured him and tossed him into various German prisoner-of-war camps for five years. The Germans repeatedly interrogated him: Are you a Jew? Where are you from? He revealed his Jewish identity, confident that the authorities would discover this information. But he realized that this identity was not entirely fixed. He decided to live under the pretense as a French Jew. Had the Germans discovered his social identity as a Polish Jew, he would have met certain death.

The Five Pillars of Identity

1. Beliefs are your convictions, principles, and morals.

2. Rituals include your meaningful customs and ceremonial acts, whether holidays, rites of passage, regular prayer, or evening dinner with the family.

3. Allegiances are the deep loyalties you feel toward a family member, friend, authority figure, nation, tribe, ancestor, or any other person, place, or thing, whether real or mythical.

4. Values represent your ideals, which can be explicit (“Our nation values liberty and justice”) or embodied in a memorable narrative (“I remember hearing about how grandfather fought day and night for this land”).

5. Emotionally meaningful experiences are intense events, positive or negative, that define a part of your identity. They comprise everything from the day you got married to the hour your first child was born, the moment your parent slapped you to the memory of mass violence conducted against your group.

Core identity is not completely fixed.

My ten-year-old, Noah, competed in a recent soccer match, scoring seven points for his team while the opposition scored none. So with only one minute left in the game, the coaches decided to switch him to the other team. Noah scored two goals for his opponents and ended up “losing” the game two to seven. He felt frustrated the whole evening, for in the course of seconds, his allegiance had shifted from one team to the other.

But Noah's core identity had not undergone a complete makeover. He was at summer camp and felt no strong attachment to either team. Had this been the World Cup and had he been switched to the opposing team, he would have struggled tremendously to redefine his allegiance. Core identity has some fluidity, but the deepest pillars of identity are extremely entrenched.

A group's core identity also can change. A company can redefine its guiding values but remain the “same” company, just as a political party can modify its essential beliefs and remain the “same” political party. In fact, groups are constantly negotiating the boundaries of their identities, deciding who is “in,” who is “out,” and even what it means to be “in.” It is as though there were a circle representing the group, and members negotiate what values, beliefs, and rituals belong within that circle. Political, religious, and social groups often keep their traditional social labels despite redefining the fundamental meanings of those labels.

While your core identity is often resistant to change, another facet of identity is more malleable and provides a powerful pathway for resolving even the most emotionally charged conflicts.

Relational Identity: The Hidden Source of Leverage

Your relational identity is the spectrum of characteristics that define your relationship with a particular person or group. When interacting with your spouse, do you feel distant or close, constrained or free to be as you really are? While your core identity seeks meaning in existence, your relational identity seeks meaning in coexistence. It changes constantly as you negotiate the nature of a relationship, which means that you have tremendous power to shape it.

To illustrate the concept of relational identity, look at the image below.

Before reading on, decide which square is darker, A or B.

The answer: They are the same. Despite the perception that square A is darker than square B, they are in fact identical. (If you remain in doubt, cover everything but squares A and B.) The optical illusion is a result of the fact that you perceive not the objective reality of the boxes but each box relative to the other.

This same perceptual dynamic holds true for differences of identity.

You have a core identity that remains distinct, yet what matters in reconciling a conflict is not just your core identity but also your relational identity—how you perceive who you are in relation to others, and how they perceive their relation to you.

Affiliation: How Close or Distant Do You Feel to the Other?

Affiliation denotes your emotional connection with a person or group.

Stable, constructive connections tend to produce positive emotions and a desire to cooperate, even in times of war.

The flip side of affiliation is rejection.

Neuroscientists have discovered that the anguish of social rejection registers in the anterior cingulate cortex, the same part of the brain that processes physical pain. Your brain responds to rejection much as it does to a punch in the gut: Once hit, you resist cooperating, even if doing so goes against your rational interests, and attempts to resolve your conflict become far more difficult.

Autonomy: How Free Are You to Be Who You Want to Be?

“Autonomy” refers to your ability to exercise your will—to think, feel, do, and be as you would like without undue imposition from others.

In everyday life, there are differences of opinion about how much autonomy is appropriate or to be expected, just as there are variations in how much affiliation is acceptable.

The race car driver wants to drive one hundred miles per hour on local roads because he loves to feel the rush of speed; families who live in the area want slow and cautious driving. A girl wants to wear a headdress to school; administrators demand everyone wear a standard uniform. The very same laws, policies, and norms formulated to hold the fabric of society together can also tear it apart at the seams, generating what Freud called the discontent of civilization.

The Bottom Line: Making One from Two

In a conflict, the core relational challenge is to figure out how to satisfy your desire to be simultaneously one with the other party (affiliation) and one apart from the other party (autonomy). Fundamentally, how can you coexist as both two ones and one set of two? Both autonomy and affiliation are intrinsic to any relationship, and your ability to keep them in equilibrium is paramount to harmonious relations. Children, for example, try to fit into their families and find their own independent voices as they mature. A romantic couple tries to balance the desire to cultivate their relationship while preserving some “alone time.”

In a merger, senior management seeks to create a singular organizational corpus as individual departments struggle to maintain cultural and political autonomy. Even more broadly, international organizations such as the United Nations work to advance a global ethos of peace and at the same time to respect the unique values of member states. At a deeper level, the ability to transcend the tension of autonomy and affiliation represents life's central ethical challenge—a point that Confucius understood well. It is told that he conceived of heaven, earth, and humankind as parts of a singular universe, a Great Whole. He observed that as we live our lives, we have the opportunity to pass through deepening spheres of existence. The shallowest is to live in the natural world, governed only by instinct. Once we discover our ego, we realize we have the autonomy to enhance our place in the world; we can self-actualize.

Eventually we come to perceive not only our own ego, but also the greater social order; we enter the moral sphere of existence and feel obliged to serve humanity. Finally, we realize that social order itself is but a part of the Great Whole, which transcends autonomy and affiliation in pursuit of the good of all.

Ch 3: A Way Forward

Only those who attempt the absurd will achieve the impossible.

I think it's in my basement . . . let me go upstairs and check. —M. C. ESCHER

How Do You Know When You Are in It?

The Tribes Effect is fundamentally an adversarial, self-righteous, closed mindset.

(1) Adversarial.

The Tribes Effect causes us to view our relationship with the other side through an adversarial lens, magnifying differences between us and minimizing similarities. Even if we feel close to the other person, the Tribes Effect instigates a kind of relational amnesia, in which we forget all the good things about our relationship and recall only the bad.

At Davos, for example, the leaders walked into our workshop as colleagues with innumerable commonalities, but quickly became adversaries and stuck to a divisive disposition. Philosopher Martin Buber describes this as a transformation from an “I-thou” to an “I-it” relationship. The other is no longer a fellow human but a savage it.

(2) Self-righteous.

The Tribes Effect breeds the self-serving conviction that our perspective is not only right but also morally superior.

Legitimacy stands on our side, and we prepare a rationale to defend it. Even when a warring group commits an act as violent as a massacre, “the butchers often have a clear conscience and are amazed to hear themselves described as criminals.” Indeed, in the Tribes Exercise I often observe each group contemptuously blaming the others: “How could you choose yourtribe over global survival?” Tribes rarely acknowledge their own critical role in bringing about the world's demise. Self-righteousness is easy to recognize in others, but less obvious in our own behavior.

(3) Closed.

The Tribes Effect molds our identity into a fixed entity. In this closed system, we come to characterize ourselves and the other side as immutable. Rather than listening to the other side to learn about their concerns, we critique their perspective and condemn their character. But we dare not criticize our own perspective, for we fear being disloyal to our own identity.

What Triggers the Tribes Effect?

When our identity feels threatened, we tend to react with a rigid set of behaviors that neuroscientists call a threat response. This response can be simple, such as instinctually retreating when we see a snake slither before us, or more complex, such as the Tribes Effect itself, which aims to protect not only our body, but our mind and spirit.

The Tribes Effect triggers when a meaningful aspect of our identity feels threatened. This means that even a seemingly small disagreement can elicit a strong emotional reaction, a dynamic that Freud termed the narcissism of minor differences. The more alike we are—whether siblings, neighbors, or religious brethren—the more we will compare ourselves with one another and feel threatened by minor differences. At Davos, for example, delegates argued over whether “humanitarianism” or “compassion” represented a more important core value. While an outsider might perceive this distinction as insubstantial, insiders viewed it as an existential threat. Backing down to another tribe would have deflated their own tribe's significance.

This same dynamic leads marital couples to fume chronically over “trivial” differences, just as it leads brother to turn his back on brother during civil war. Humanity's infinite commonalities pale in comparison to a singular difference that takes on outsized importance. In short, the trivial can become more than a matter of trivial concern.While a threat to identity triggers the Tribes Effect, respect of identity produces harmonious relations. We feel the freedom to be who we want to be and enjoy our emotional connection with others. But when our sense of autonomy and affiliation feels endangered, protective emotional forces swoop in, and self-protection trumps collaboration.

Counteract the Five Lures of Your Tribal Mind

Overcoming the Tribes Effect requires a strategy much like that adopted by the Greek hero Odysseus. As he navigated his ship home after ten long years of fighting in the Trojan War, he met the goddess Circe, who warned him of a danger he would face on his journey: beautiful Sirens with enchanting voices who bewitched sailors, compelling them to steer toward the Sirens' island, where their ships would crash against the shoreline's sharp rocks and leave “heaps of bodies.” Before he set sail, Odysseus ordered his crew to put wax in their ears and tie him to the mast. If he begged to be released, they were to refuse his orders and bind him even tighter. With this plan in place, Odysseus and his men sailed safely past the Sirens.

The Tribes Effect, like the Sirens, draws you toward it. The more deeply you are enveloped in its emotional folds, the more difficult it becomes to resist its pull. In an emotionally charged conflict, this attraction originates in a powerful set of emotional dynamics, which I call the Five Lures of the Tribal Mind. The chart below provides an overview of them.

The Five Lures of the Tribal Mind 1. Vertigo is a warped state of consciousness in which a relationship consumes your emotional energies.

2. Repetition compulsion is a self-defeating pattern of behavior you feel driven to repeat.

3. Taboos are social prohibitions that hinder cooperative relations.

4. Assault on the sacred is an attack on the most meaningful pillars of your identity.

5. Identity politics is the manipulation of your identity for another's political benefit.

Section 2: The Five Lures of the Tribal Mind

Ch 4: Vertigo

The Disorienting World of Vertigo

The psychological force drawing the professor and his wife toward the Tribes Effect is something I call vertigo: a warped state of consciousness in which a relationship consumes your emotional energies. As the couple slipped into vertigo, a hypnosislike state overcame them; each fixated on the other's angry words, determined not to resolve the argument but to win it.

The word “vertigo” derives from the Latin vertere, meaning “to turn.”

You may know the term from Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo, which depicted it as dizziness brought on by a fear of heights. Modern medicine differentiates a variety of disorders in which people experience a spinning sensation. I have borrowed the term to describe the unique condition in which one feels trapped within a dizzying state of adversarial relations. The argument between the professor and his wife started benignly enough. But as egos were bruised, each spouse passed an emotional threshold and fell into the spiraling state of vertigo.

Picture vertigo as a tornado surrounding you and the other side. Its swirling walls prevent you from seeing anything beyond the boundaries of your conflicted relationship, just as the professor and his wife saw nothing beyond the frenzy of their squabble. Strong gusts of wind blow at you and the other side, heightening the intensity of your emotional experience and turning anger to rage, sadness to despair. Standing at the center of this tornado, you can see the sky above, a vivid image of your greatest fears for the future, while the uprooted ground beneath you reveals your painful past.

This tornado can keep you trapped in the Tribes Effect for hours, days, or even generations.

Obstacles

1. Vertigo Afflicts You Outside Your Awareness

2. Vertigo Diminishes Your Capacity to Self-Reflect

- You mindlessly reenact a conflict script.

- You suffer diminished capacity for self-conscious emotions.

- You stereotype the other party.

3. Vertigo Constricts Your Perception of Time and Space

In a very literal sense, vertigo warps your sense of time and place. Your focus narrows to exclude all else but the situation immediately before you —without your realizing that this is happening. The professor and his wife were so consumed by their conflict that they failed to notice either the onlookers who had gathered or the lengthy passage of time. Vertigo affects your state of consciousness to such an extent that while your world spins upside down, you still believe you are right side up.

4. Vertigo Fixates You on the Negative

- Past pain haunts you.

- Memories of a feared future consume you.

How can you have memories of the future? Aren't memories an artifact of past experience? Not always. In an emotionally charged conflict, you tend to imagine worst- case scenarios about what the other side might do to you in the future, such as to humiliate or attack you. If such an imagined scenario possesses sufficient emotional charge, it can imprint in your memory, until over time you may forget that it is something you invented. Consequently, your brain houses a freestanding memory as a frightening eventuality, and you experience the remembered narrative as though it actually occurred. Your feared future becomes a de facto past, and this “reality” pulls you toward the Tribes Effect. Now you have “proof” that the other side cannot be trusted.

Psychologically, a chosen trauma from the past is no different from a memory of a feared future; they have the same effect, because both involve incorporating an emotionally significant scenario into a current conflict. An ethnic group might conceivably go to war based upon a chosen trauma from five hundred years ago or one they fear will occur five hundred years from now. Strikingly, no member of the group actually experienced either event.

But to them it is a story that evokes an emotional response powerful enough to motivate a call to arms.Vertigo creates an echo chamber of negative sentiment. Because you immerse yourself in a closed system of noxious memories, trivial issues can magnify in importance. In the Tribes Exercise, for example, the world commonly explodes because a tribe feels excluded. When the planet's very survival is at stake, concerns about exclusion should not be such a significant matter. But within the distorted realm of vertigo, exclusion is a potent threat to the tribe's identity. The argument over the bedspread is equally trivial, but from the distorted vantage point of vertigo, the professor's identity felt battered, heightening the issue's resonance.

Breaking Free of Vertigo

| Obstacle | Strategy |

| 1. Vertigo afflicts you outside your awareness. | 1. Be aware of the symptoms of vertigo. |

| 2. Vertigo diminishes your ability to self-reflect. | 2. Jolt your relationship out of its trancelike state. |

| 3. Vertigo constricts your perception of time and space. | 3. Expand your field of vision. |

| 4. Vertigo fixates you on negative memories. | 4. Externalize the negative. |

Step 1: Be Aware of the Symptoms of Vertigo

First, learn to identify the symptoms of vertigo.

Are you consumed by the conflict? Do you view the other as an adversary? Are you fixated on the negative?

Second, stop. The moment you become aware that you are slipping into vertigo, take a breath. Then take another. Slow down. Wait until you regain perspective before continuing the discussion.

Third, name it. The simple act of naming vertigo can profoundly reduce its power over you. By giving it a label, you turn your abstract swirl of emotions into a discrete “it” to discuss and surmount, reactivating your capacity for self-reflection. When my wife and I recently got into an argument that threatened to lose its bearings, she said, “I feel like we're slipping into vertigo. Do we really want to spend the afternoon arguing?”

Merely recognizing the onset of vertigo helped us resist its allure. We agreed to discuss the issue at hand for a few more minutes and, should we not reach a resolution, to take a break, which would keep us from getting lost in the muddled space between us.

Step 2: Jolt Your Relationship Out of Its Trancelike State

Remember your purpose.

Use the power of surprise. A second strategy to jolt your relationship is to draw on the power of surprise. Imagine what might have happened if, during that ugly scene in the mall, the professor had cast aside his conflict script and startled his wife out of her anger. Suppose, for example, that after she snapped that she was no longer even sure why they had ever gotten married, he had responded, “In my case, because I loved you. And I love you now. Should we go back and look at the bedspread?” His wife's anger might well have begun to deflate in response to his solicitude. Soon they would have felt their sense of perspective returning, along with their ability to think rationally and generously. They might even have laughed about the absurdity of it all: Was a bedspread really enough to tear them apart like this? The well-placed jolt can be equally effective in international relations.

Consider the famous visit of Egypt's President Sadat to Israel. Until 1977, no Arab leader had ever made an appearance in the Jewish state. Israel and Egypt had fought four wars, and Israel maintained control over the Sinai Peninsula, a region of Egypt it had captured in the 1967 conflict. Israelis felt little hope that peace could ever exist between the two nations. Then, in an act that surprised the world, President Sadat landed at Ben Gurion Airport and spent thirty-six hours in Israel, addressing the Knesset and meeting with key leaders. Sadat's visit jolted the Israeli public into seeing Egyptians not as adversaries but as partners, leading to a peace agreement between the two countries.

An unexpected apology may be the most powerful jolt of all. As the couple argued in the mall, the professor could have taken a deep breath,paused, and told his wife, “I've said a lot of mean things to you just now.

I'm sorry. I spoke without thinking.” That admission would have been likely to stop her in her tracks, surprised at this sudden turn of events. If she felt her husband's apology was a sincere expression of remorse, the space between them would have opened for constructive conversation.

- Summon a legitimate authority.

- Change the subject.

Step 3: Expand Your Field of Vision

Broaden Your Sense of Space

- Alter your physical environment.

- Look at the conflict from a new vantage point.

In vertigo, the issues at hand can take on such gravity that backing down from your position feels like a crushing defeat. You can counter this by examining your situation from a broader vantage point.

Imagine taking a spaceship to the moon, looking down at the Earth, and realizing just how small your conflict is in the grand scheme of things.

Frank White, a colleague at Harvard, studied the psychology of astronauts and discovered that after they return to Earth, they share a profound cognitive shift in their view of human relations: To them, all the world's troubles seem secondary to the goal of embracing the Earth as a whole. He calls this expansive perspective the overview effect. Even if you never make it into space, you can still benefit from this exercise in perspective.

You also can change your vantage point in more modest ways.

Imagine your conflict is a twelve-story building, and both parties are on the top floor. Up there the situation is intense, gut-wrenching, an emotional whirlwind. Now imagine telling the other party in your conflict to wait there on the twelfth floor for a few minutes. You enter the elevator. As you travel downward, floor by floor, you take a deep breath and feel the calm that arrives as you exhale. You begin to perceive the other party's feelings of vulnerability and can better appreciate your own. By the time you reach the ground floor, you more clearly understand each side's contribution to the conflict. Now press the button to return to the twelfth floor and finish your conversation.

Reorient Your Sense of Time

Slow down.

Because vertigo causes a chain of reactive emotions, it may be helpful to slow the tempo of the conversation and just listen—not to register incoming attacks, but to detect underlying emotions. You might also slow communication: Wait a few hours before responding to the e-mail that angered you. Speak more slowly, reminding yourself to take a momentbefore responding. Or, if you are involved in an extended conversation, take breaks periodically to maintain some distance between the conflict and your emotions.

Fast-forward.

In our mall example, the professor might have said to his wife, “Pretend it's ten years from now, and we're looking back on this fight about the bedspread. What advice do you think those older, wiser versions of ourselves would give us?”

I drew on this fast-forwarding technique several years ago when designing and co-facilitating a private negotiation workshop for Israeli and Palestinian negotiators. Rather than asking them to discuss ways to break their impasse—which would have quickly brought them into a state of vertigo—I challenged them to imagine what a peaceful state of coexistence between them would look like twenty years in the future, from an economic, social, and political perspective. That question transformed a potential battleground into a collaborative brainstorming session.

Envisioning a specific future made that future more tangible than the abstract fears brought on by vertigo. That session planted the seeds for a major peace initiative.

Rewind.

When my wife and I get into a conflict, vertigo regularly tempts us to turn a short-lived argument into a long-term fiasco. On those occasions, I get myself to remember our relationship at its happiest: the first time I flirted with her, the day we got married on Block Island, the feeling of laughing at the ridiculous jokes of our three boys. These memories open up space in my mind to decide whether I want to walk down the path toward vertigo—and I almost always choose not to.

I say “almost always” for two reasons: First, I am human, and sometimes the pull of vertigo is too strong for me to resist. Second, vertigo, when properly controlled, does sometimes have its merits. For example, you might think to yourself, I'm in vertigo now, but it feels good to express myself. However valuable that may be at a given moment, I recommend that you set a specific time limit at which to end it: Let me look at my clock, and in ten minutes I'll propose that we take a break. While such deliberateness of purpose may sound unnatural, it helps you establish an important mechanism to break through vertigo's hold on your sense of time.

Step 4: Externalize the Negative

You need a strategy to combat vertigo's obsessive focus on the negative— one that enables you to reveal distressing emotions without reveling in them. But how do you formulate one?

Name the Dynamic

Oscar Wilde once remarked that “man is least himself when he talks in his own person; give him a mask and he will tell the truth.” In a conflict, talking directly about distressing emotions can feel combative, especially if you see your pain as a result of the other's words or behavior. You need a technique to allow you to talk about emotional obstacles without specifically talking about emotions—in other words, to help you have a direct conversation in an indirect fashion. You need to externalize the negative—that is, to use symbolic communication to discuss the emotional forces weighing down your relationship.

Rather than reacting to conflictual dynamics at play in a conversation and heading straight toward vertigo, you can identify those dynamics and strategize aloud about how best to deal with them. By objectifying your subjective experience, you give a name and concrete reality to the intangible forces driving your conflict.

Ch 5: Repetition Compulsion

We are, all of us, creatures of the repetition compulsion.

—DANIEL SHAPIRO,

NEGOTIATING THE NONNEGOTIABLE

The Anatomy of the Repetition Compulsion

Repetition is a fundamental aspect of human life. You wake up at the same time each morning, eat the same types of food, and laugh at the same kinds of jokes. Some repetitive behaviors are helpful—but others, like the repetition compulsion, can do harm.

Sigmund Freud initially presumed that human beings are fundamentally driven by the pleasure principle, which leads them to seek pleasure while avoiding pain. This theory made sense—until Freud encountered a series of paradoxes. Why, he wondered, do some people repeatedly engage in relationships that result in “unpleasure”? Is it a mere accident that each of an individual's friends eventually betrays him? That his protégés all angrily abandon him? That his romantic relationships always begin with a bang but fizzle out at the three-month mark? Freud conceived of the repetition compulsion as a way of explaining this “demonic force” that is “more primitive, more elementary, more instinctual than the pleasure principle which it overrides.”

I view the repetition compulsion as a dysfunctional pattern of behavior that you feel driven to repeat. It is a more complex form of a habit, which springs to life when a stimulus produces a desired response. (For example, you crave caffeine, so you mindlessly walk to a café and order a latte. The stimulus produces the response you wished for—and soon you develop aserious espresso habit.) The repetition compulsion goes deeper, luring you to repeat that which you would rather not. You unwittingly place yourself in a self-defeating situation, unconsciously repeating an age-old pattern of behavior while assuming that it is a product of present circumstance.

To break free of the repetition compulsion, it is important to first understand how it distorts your perceptions during a conflict.

First, you suffer an emotional wound. When your identity feels violated—whether by aggression, abuse, or a catastrophic change in circumstance—the experience leaves a painful emotional wound. Consider the experience of my friend Jen. When she was seven, her father left home and never returned. His abandonment affected her deeply and gave rise to a lasting emotional scar. When she was growing up, she would play outdoors with friends but look incessantly toward the top of the street, hoping to see her father's car approaching. It never came.

Second, you exile painful emotions to your unconscious. You lock those emotions in a cell within the back corridors of your mind, hoping never to see them again. When I first met Jen, she was thirty years old, but her father's abandonment remained the most painful event of her life. She had never sought therapy, however, and rarely discussed her childhood with friends, instead confining her sadness, shame, and rage within that chamber in her unconscious, pretending those emotions did not exist.

Third, you scan hypervigilantly for any stimuli that may produce a similar emotional wound. Though Jen repressed her emotions, they refused to stay sequestered in her unconscious. They pounded the walls, banged the ceiling, and shouted incessantly. Whenever she unconsciously detected a conflict situation in her life that was even modestly suggestive of abandonment, she drew on the only experience she knew. Despite evidence to the contrary, she held firm to the belief that her husband would eventually betray her, her boss would fire her, and her best friend would end their relationship. In situation after situation, Jen cast herself as a victim of desertion. The pain of her childhood wound regularly resurfaced, turning even unrelated conflicts into painfully familiar scenarios.

Fourth, you unconsciously attempt to alleviate your painful feelings. While the most effective way to address painful emotions is to unearth them and work through them head-on, facing them can befrightening. The repetition compulsion offers an alternative route—it attempts to help you master them without dealing directly with them.

But it has limited effectiveness, because it restricts your behavioral repertoire. On the one hand, the repetition compulsion may encourage you to unconsciously “act out” painful emotions, repeating the very conditions that hurt you initially in the hope that this time you will “master” your age- old trauma. Whenever Jen's husband traveled on a business trip, she felt deeply abandoned, and when he would return home, she would pick fights with uncharacteristic intensity, with the secret hope that this time she would be able to achieve command of her situation. But of course the more she yelled, the more distanced her husband felt, leaving her repeatedly promoting the very abandonment she so deeply feared.

On the other hand, you may avoid situations in which your repressed emotions will emerge. For example, Jen remained alert to any context in which someone might abandon her. When she believed she had identified such a prospect, she would take preemptive action, distancing herself before the other party could do the same to her. The result of her premature withdrawal was predictable: Her friends felt rejected—and abandoned her.

Once again Jen recreated the very circumstances of abandonment she was attempting to master.

While the repetition compulsion can cause you ongoing grief due to its self-defeating nature, it is in some respects well intentioned and a necessary part of the healing process. It prompts you to wonder, Do I really need to endure this pain again? And ultimately it is that very question that will help you finally halt the repetition compulsion.

Barriers to Breaking Free

1. The Repetition Compulsion Happens Automatically

2. The Repetition Compulsion Feels Education-Resistant

3. The Repetition Compulsion Takes Control of Your Feelings

4. The Repetition Compulsion Feels Ingrained

Strategy for Breaking the Repetition Compulsion

1. Catch the repetition compulsion at the earliest possible moment.

2. Resist the pull to repeat the same patterns.

3. Reclaim power over your feelings.

4. Add a new routine to your repertoire.

1. Catch the Repetition Compulsion at the Earliest Possible Moment: The TCI Method

Just as the police are better able to catch a bank robber if they have a mug shot, you will be more effective at halting the repetition compulsion with a picture of your typical pattern of conflict.

Start by identifying a relationship that repeatedly comes under strain from conflict. Do you bicker time and again with your spouse, your kids, or a colleague? Conflict is inevitable—you can expect to have differences with other people—so look specifically for patterns of recurrent mayhem, situations in which you repeatedly avoid, confront, accuse, blame, or otherwise sabotage straightforward resolution. If you keep finding yourself having the same sort of disagreements with the same unsatisfying results, the repetition compulsion is likely at play.

Once you identify this recurring conflict, map out the key pattern that you tend to repeat, including the trigger, cycle of discord, and impact (“the TCI method”). Awareness of this pattern empowers you to stop its repetition. The chart here provides a guide to get you started.

The Lure of the Compulsion Do You Repeatedly Fear Being . . .

Abandoned Alienated Dependent Emasculated Empty Enmeshed Helpless Inferior Insignificant Patronized Powerless Rejected Subordinate Used Weak Worthless

3. Reclaim Power over Your Feelings

Clarify the Emotional Contours of Your Current Conflict While some of your emotions will undoubtedly be stirred by the circumstances of your current conflict, others will likely be a product of the repetition compulsion. To detect the latter, ask yourself three powerful questions: 1. Are these issues mine, or are they yours? Distinguish the ones that drive each of you to conflict.

2. Is this now, or is this then? Attune to past wounds affecting your present experience.

3. Did I do this, or did you? Notice what you each contributed to the conflict—and whether any blame may be misplaced.

Work Through Emotional Wounds

First, identify a deeply sensitive issue that repeatedly triggers strong emotions, such as fear of rejection, abandonment, or inferiority.

Second, trace the origins of that issue.

Third, explore painful feelings that accompany the wound.

Fourth, release the pain. This requires both a conscious decision and conscious effort. Once your pain has been “heard,” you can let it go; it has said what it needs to say. Jen realized she could decide whether to hold on to the emotional burden of abandonment—and chose to release it. The process was emotionally wrenching but purifying.

Fifth, turn your wound into a source of strength. The scars of Jen's abandonment will remain with her forever, even though she has released the pain of her childhood memories. Rather than seeing herself as a victim of those circumstances, however, she has reframed her perspective, vowing to be a beacon of love to her own family and friends and to never abandon a friend or relative in need.

4. Add a New Routine to Your Repertoire

While you cannot change the other's behavior, modifying your own routine can productively affect the relationship. To devise a new routine, recall your typical pattern of conflict, which you mapped out in the chart here. Now conceive a constructive alternative to this behavioral repertoire, considering what steps you might take to do the following.

Preempt the trigger.

When you know what sets you off, you are better equipped to halt it. If you and your spouse frequently fight over finances, you might agree to discuss money matters only with a financial adviser present, or commit to uphold a monthly budget.

Replace a behavior in the cycle of discord.

Review your cycle of discord and choose one behavior to alter. For example, imagine a typical cycle of discord between you and a colleague over project plans. She criticizes you, you criticize her, she criticizes you again, and you withdraw. One alternative approach would involve you empathizing with her situation after her initial attack.

Replace the entire cycle of discord.

Envision a constructive cycle of dialogue to replace your current one. The two founding partners of a technology start-up company heeded this advice. As investments in their company increased, the intensity of their arguments escalated. Realizing that their deteriorating relations might jeopardize their company, they sat down and articulated an alternative process to deal with their differences. Rather than engage in a cycle of attack and counterattack, they agreed to shareperspectives and search for common ground, an approach that proved much more effective for their company and their relationship.

Guard Against Relapse

The decision to change your fundamental patterns of behavior requires a reconceptualization of your identity—a task that can be extremely difficult.

I remember watching my loving grandmother, whom I called Nan, struggle to quit smoking. As the years wore on, the habit took its toll. Even with an oxygen tank helping her to breathe and lung cancer spreading, she would still sneak an occasional cigarette. The habit cost her her life.

While addiction certainly was a contributing element to my grandmother's behavior, I believe identity was her core obstacle. She identified herself as a smoker—I saw her that way too—and she could not envision herself otherwise; it had been part of who she was for nearly fifty years.

Revise Your Self-Image Breaking free of the repetition compulsion requires you to envision a new self-image and visualize yourself enacting it. You might even choose a role model and channel that person's qualities in your next conflict. What will it feel like to act as that person? What might you say if the other side offends you? What can you do to generate their goodwill? Rehearse your response in your mind again and again until it becomes second nature.

Devise a Plan to Guard Against Relapse William James wrote, “Accumulate all the possible circumstances which shall reinforce the right motives; put yourself assiduously in conditions that encourage the new way; make engagements incompatible with the old; takea public pledge, if the case allows; in short, envelop your resolution with every aid you know.” Perhaps the most powerful way to live up to James's exhortation is to enlist help in guarding against the repetition compulsion's return. Jen, for example, knew that while she was ultimately responsible for pulling herself out of its hold, the combined effort of Mark's assisting her in achieving that goal was ultimately more effective than Jen's attempting it alone.

Guard Against the Unguarded Moment Before engaging with the other side, reflect on what they might say or do that could trigger you to repeat a destructive pattern of behavior. Then consider the most important question: What might you say or do to avoid the repetition compulsion? When I mediate a heated dispute, I establish norms to prevent the disputants from returning to the repetition compulsion: “The goal of our session is to help you come to a better understanding of each other's perspectives and to explore ways to reconcile your differences. I recognize you are in a rut—and it's easy to fall back into your same old conflict dynamics. So our goal today is to have a different conversation, a more productive one in which you listen to learn rather than to defend.” During the mediation, I listen carefully to ensure that each disputant treats the other with respect. If either party offends the other, I immediately interrupt to remind both parties of our norms—and redirect discussion toward constructive dialogue.

There are times, however, when you are likely to let down your guard and no mediator is there to rescue you. With a little bit of forethought, you often can anticipate these situations and make a plan to prevent them. For example, during vacations with extended family, my wife and I used to engage repeatedly in an emotionally draining pattern of conflict, in which we felt angry over some perceived offense, then felt embarrassed and ashamed that our relationship was not “perfect,” at which point we would pretend our connection was fine, which merely exacerbated our tension.

Once we realized this pattern, we made a plan to guard against it, agreeingto talk privately each evening to vent any frustrations and emotionally reconnect, in effect keeping the repetition compulsion at bay.

Ch 6: Taboos

What Are Taboos?

Taboos are social prohibitions—actions, feelings, or thoughts that a community deems unacceptable. The word “taboo” was introduced into the English language in 1777, when British explorer James Cook sailed the HMS Resolution across the Pacific to what were then known as the Friendly Islands and are now known as Tonga. Cook discovered that the island's inhabitants used the word tabu to refer to all that was forbidden, and the term soon found its way into English parlance—perhaps because it handily describes a dynamic familiar to people in just about every culture.

Every taboo has three components—a prohibition, a punishment for breaking it, and protective significance.

Prohibition

A taboo identifies certain feelings, thoughts, or actions as being off-limits, creating a boundary between what is acceptable and what is forbiddenwithin a community to which you belong, whether your family, your workplace, or broader society. For example, premarital sex is acceptable in some cultures but taboo in others. A taboo is thus a social construction and is prohibitive only to the extent that we tacitly agree on its restriction. Curse words hold no inherent power: If you were to say an English obscenity calmly to someone who speaks no English, he would stare at you just as blankly as if you had said the word “chair.” We attach prohibitive meanings to words, thoughts, and actions—which means we can also attach new meanings to them.

Punishment Every taboo comes with punishment for violation. The more intense the punishment, the more likely you are to feel pressure to comply with the taboo. You either hang together or get hanged. Typical penalties for breaking a taboo:

Don't talk about that issue . . . or I will walk out the door.

Don't negotiate with those people . . . or we will ostracize you from our community.

Don't eat that type of food . . . or you will break a religious covenant.

Don't touch that dead body . . . or you will contaminate your body and soul.

Protection

Taboos act as unwritten social rules guarding you from saying or doing things that offend values deemed important by society, or by the powerful members within it. Some taboos protect you from committing sacrilege. For example, in the Jewish religion it is taboo to drop the Torah, with one tradition commanding the violator and those who witness the act to fast for forty days. Other taboos shield you from dangers both moral and practical —the taboo against adultery helps maintain a stable social and familial order and also reduces the spread of sexually transmitted disease. Still others may protect your identity from criticism, as when rules of politeness inhibit people from disparaging one another's views.

Taboos bear a close functional resemblance to the repetition compulsion: Both are imperfect systems designed to defend your identity from harm. The repetition compulsion uses psychological mechanisms such as repression to protect you from undesirable thoughts, feelings, and behavior, whereas taboos use social mechanisms such as ostracism to protect you from unacceptable thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. And just as attempts to break the repetition compulsion are met with psychological resistance, attempts to break a taboo are often met with social resistance. In Marrakesh, as BBC host Nik Gowing requested that Dahlan speak English,

Dahlan refused; the harder Gowing pushed, the more strongly Dahlan resisted.

Why Do We Stumble over Taboos?

Several obstacles often make it difficult to deal with taboos.

1. We Are Unaware of a Taboo

2. We Fear Discussing the Taboo Issue

3. We Have No Framework

How to Navigate Taboos

| Stumbling Block | Strategy |

| 1. We are unaware of a taboo. | 1. Become aware of taboos. |

| 2. We fear discussing the taboo. | 2. Establish a safe zone. |

| 3. We have no framework to decide how to treat a taboo issue. | 3. Make an action plan: the ACT System. |

Ch 7: Assault on the Sacred

Welcome to the World of the Sacred

When your deepest beliefs feel threatened, you may find yourself mired in the fourth lure of your tribal mind, an assault on the sacred. This is an attack on the most meaningful pillars of your identity: any matters so deeply significant that they feel sacrosanct, exempt from debate. Spouses passionately disagree over which values to instill in their children.

Employees reject a colleague who criticizes core institutional values.

International negotiators deadlock over who should control sacred land.

An assault on what you hold as sacred triggers a powerful emotional reaction that to the outsider may seem an overreaction, irrational. But that is not the case from your own vantage point. The central purpose of identity is to help you make meaning of your experience in the world—and the sacred represents your deepest form of meaning. An assault on the sacred cuts you to the quick, shaking the most sensitive pillars of your identity and raising fears that it will not withstand the blow.

What Is the Sacred? I define the sacred as that which we perceive to be imbued with divine significance. The “divine” need not refer to a specifically religious entity.

While the object of one's veneration can be a deity, prophet, or holy text, it also can be a family member, beloved place, or cherished event. Just as a religious person holds hallowed scripture as sacred, a nationalist views his country's flag as a sacred object never to be defaced, and a widow holds sacred her departed spouse's ashes.

We revere as divine whatever we view as imbued with infinite, intrinsic, and inviolable significance.

Infinite

My love for my children, and their worth to me, is boundless. But love that is nonquantifiable presents problems in conflict resolution. When negotiators are forced to quantify the sacred, the act feels both morallyoffensive and practically impossible. After a deadly act of terrorism, how should a government distribute compensation to the families of the victims? Should the amount vary by recipient, based on such criteria as the victim's age and income? Asking such questions is discomfiting, and making the resulting decisions is enormously difficult.

Intrinsic

The divine holds intrinsic significance. It is not just that I feel my children are sacred; from my perspective they are sacred in their very being. Their infinite value resides in them, not in my belief about them. We perceive the significance of the divine to be an innate feature of the object of our reverence.

Inviolable

Because every aspect of the divine possesses infinite worth, to insult one part of a sacred entity is to insult its entirety. It is immaterial whether someone burns ten pages from the Bible or Koran or crosses out a single word; the offense is sacrilegious. To dismiss an assault on the sacred as “minor” neglects the fact that any offense committed against a revered object, however slight, can feel enormous to the offended party.

Obstacles to Negotiating the Sacred

1. We Are Unaware of the Sacred

2. We Conflate the Sacred and the Secular

3. We Fail to Give Due Respect to the Sacred

4. We Refuse to Compromise on Sacred Issues

| Obstacle | Strategy |

| 1. We are unaware of the sacred. | 1. Sensitize to the sacred. |

| 2. We conflate the sacred and the secular. | 2. Disentangle the sacred from the secular. |

| 3. We fail to give due respect to the sacred. | 3. Acknowledge what each side holds sacred. |

| 4. We refuse to compromise on sacred issues. | 4. Problem solve within each side's sphere of identity. |

A Strategy for Negotiating the Sacred

1. Sensitize to the Sacred

Do You Feel a Threat To . . .

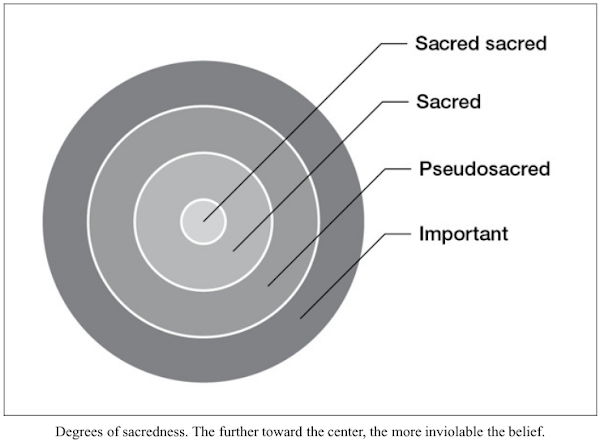

1. Sacred beliefs—vital cultural, religious, or social convictions? 2. Sacred rituals—meaningful activities or spiritual practices? 3. Sacred allegiances—intense loyalty to close friends, family members, or political allies?4. Sacred values—deeply held ideals or principles? 5. Sacred experiences—emotionally meaningful experiences that integrally define your identity?

Ch 8: Identity Politics

There is no history of mankind, there are only many histories of all kinds of aspects of human life. And one of these is the history of political power. This is elevated into the history of the world.

—KARL POPPER

Consider what the following three scenarios have in common:

1. The rocky marriage.

A friend named Kathy calls me up in tears.

Her marriage to Joe is falling to pieces. From a distance, I can see the dynamic at play: While their differences are not insurmountable, their parents unwittingly mobilize them to battle. Every time Kathy calls up her mother for consolation, her response is “You are absolutely right, Kathy.

Joe is wrong—and as self-centered as ever. I honestly don't know how you live with him.” Meanwhile, Joe's mother supports his perspective and dismisses Kathy as “difficult” and “stubborn.” The parental support is tearing their marriage apart.

2. The company clash.

A multinational company is in the midst of a turf war between the research and marketing divisions. Each fears the other is out to sabotage its productivity and “steal” resources. As preparations begin for next year's budget, each division's leader meets discreetly with the CEO to advocate for her own division as the “soul” of the company and a wiser investment of the company's resources.

3. The turbulent state. Serbian president Slobodan Milošević stands before a huge crowd in Gazimestan, Kosovo, invoking Serbia's defeat in Kosovo six hundred years earlier as a nationalistic call to arms. “Let the

memory of Kosovo heroism live forever!” he exclaims. “Long live Serbia! Long live Yugoslavia! Long live peace and brotherhood among peoples!”

Many observers credit this speech as the breaking point leading to the Kosovo war.

In each of the previous examples, the fifth of the lures—identity politics—is at play. Identity politics can jeopardize the emotional life of a marriage, the efficiency of an organization, or the security of a region.

Unlike the other lures, it is often deliberately used to manipulate and divide people, fueling the Tribes Effect. But armed with the right strategies, you can use identity politics to improve your relationships and reach mutually satisfying outcomes to conflicts.

What Is Identity Politics?

Humans are, by their nature, political animals—an observation made by Aristotle more than two thousand years ago. Your every word and action conveys a message about your political standing in relation to others. You may nestle yourself in good relations with your boss or compliment a friend to strengthen your bond. Simply put, politics is about “who gets what, when, and how.”

Identity politics, then, refers to the process of positioning your identity to advance a political purpose. You ally with specific individuals or groups within a power structure to better your odds of reaching your goals. But you also may pay a price for associating with one particular group and not another. This whole process occurs within a political space—a social circle in which people interact to make decisions. A government is the most familiar such space, but others include a marriage, friendship, or workplace.

Each of these spaces presents opportunity for discord over who gets what— and at what price.

Looking back at the three examples at the beginning of this chapter, we can now see how people positioned their identities to serve some sort of political purpose—and paid the price:

In the rocky marriage of Kathy and Joe, each mother sought to cocoon her child from emotional distress (the purpose), allying herself as a loyal advocate for her child (positioning). Each mother delegitimized the other spouse's concerns, strengthening her own child's sense of righteousness but inadvertently fracturing the couple's relations (the price).

In the company example, the research and marketing leaders aspired to gain greater financial resources (the purpose) and each met privately with the CEO to argue for her own division's superior importance to the organization (positioning). But their actions reinforced their long-standing rift and reduced organizational productivity (the price).

In the Serbia example, Milošević aspired to mobilize support for his vision of a greater Serbia (the purpose), rallying Serbian nationalism through his speech on the former battlegrounds in Kosovo (positioning). But he also sharpened the lines of division between the region's ethnopolitical groups; the subsequent violence contributed to a massive loss of lives and brought Milošević before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, where he was indicted for crimes against humanity (the price).

The Pitfalls of Politics

| Pitfall | Strategy |

| 1. Ignorance of the political landscape. | 1. Map the political landscape. |

| 2. Clinging to a negative identity. | 2. Build a positive identity. |

| 3. Reliance on an exclusive decision-making process. | 3. Design an inclusive decision-making process. |

| 4. Treated like a political pawn. | 4. Protect yourself from being exploited. |

1. Map the Political Landscape

Look for Two Levels of Political Influence

The Ladder: Who's the boss?

The Network: Who are your allies?

Stay Actively Aware of the Political Landscape

Notice when others seek to shape your identity.

Attune to the other side's political pressures.

Be alert for spoilers. Spoilers are people who try to undermine your efforts to resolve a conflict—and identity politics is a key tool in their arsenal, for conflict suits their political interests more than resolution.

2. Build a Positive Identity

Emphasize the Relentless 'We'

Define Identity in Positive Terms

3. Design an Inclusive Decision-Making Process

The ECNI Method

This process provides a template for inclusive decision making while also accounting for differences in authority. Begin by considering three key questions:

(1) What is the decision to be made?

(2) Whom does this decision affect?

(3) How much input should each stakeholder have in the decision-making process? If you believe that a stakeholder is likely to be a spoiler, you may even want to exclude them from part or all of the negotiation process—but weigh that against the risk that they may feel rejected and seek retribution.

Now draw three columns on a sheet of paper. In the first column, write the decision to be made. In the second column, list the key stakeholders the decision affects. To complete column three, employ the ECNI method, deciding which stakeholders to exclude from the decision-making process; consult before making the decision; negotiate with to reach a decision; and inform after a decision has been made.

Mia and I sat down one evening and discussed who should be part of the vacation negotiation and who should merely be consulted or kept informed. The chart here illustrates the results of our thinking. I consulted with my department chair on the date of our trip to ensure there was no major academic meeting scheduled for that time; Mia and I then consulted with our parents and kids on their interests; and finally the two of us negotiated the location and informed everyone: We would head to Block Island in the summer to catch the sun, sand, and hiking trails, and then join the in-laws over the winter holidays at Disney World. We decided topostpone any international travel until all our kids passed the toddler stage.

And we agreed that, should any of the stakeholders oppose our suggestions, we would negotiate with them. Using the ECNI Method—exclude, consult, negotiate, inform—we streamlined the politics of decision making and enjoyed a great vacation.

In Multiparty Conflicts: Clump

4. Protect Yourself from Being Exploited

Name the Dynamic—and Propose an Alternative

Enhance Your Structural Power

Forge Good Political Relations

In Sum

Identity politics is a matter of power, and power is relational: You acquire it through your relations with others. Negative identity politics traps you in adversarial relations that can spiral your conflict toward the Tribes Effect.

Positive identity politics, on the other hand, can foster cooperative relations.

The underlying strategy of positive identity politics is straightforward: Define who you are, not who you are not. Then persistently position yourself to maximize partnership and minimize resentment.

Section 3: Bridging the Divide

Ch 9: Integrative Dynamics—a Four-Step Method

There is nothing quite like listening to the late, great jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie. As he brings the trumpet to his mouth, puckering his lips and expanding his cheeks like two balloons, the sound that flows through his instrument feels rhythmic and melodious, then as choppy as a car hitting bumps in the road, then flowing again like water in a stream. As a drum sizzles softly in the background and a piano accents three off notes, Dizzy hits a potent staccato—bop-ditti-bop-bop-BOOM—disrupting the rhythm once again and then striking a downward scale with penetrating speed and bravado. This wild array of sounds and beats, discordant and discombobulated, frenzied and fanciful, weaves together in a strikingly integrated whole, a harmonious trail of musical whims.

Jazz finds harmony in dissonance. The dissonance remains, but is held together by a deeper, integrative force.

This insight is crucial to resolving an emotionally charged conflict. To heal broken relations, you need to find transcendent unity. While your core identity and the other's may feel completely incompatible, do not let the Five Lures undermine your sense of what is possible. You have the capacity to create harmony within yourself and in your relations with others. Once you believe in the possibility of transcendent unity, you open yourself up to finding it. Dizzy Gillespie undoubtedly had off nights, searching in vain for that elusive well of creative energy. At times he undoubtedly was dissatisfied with his own performance; transcendent unity can be elusive.

But his “on nights” were flawless. He integrated Afro-Cuban rhythms with Afro-American jazz, bopping up and down scale after scale in lightning-fast tempo and creating a musical whole much larger than the sum of its discordant parts.

Conventional Methods of Conflict Resolution Are Insufficient

Two conventional methods of conflict resolution—positional bargaining and problem solving—are insufficient to achieve transcendent unity in an emotionally charged conflict.

Positional Bargaining?

In positional bargaining, you and the other side take firm, opposing stances, cling tightly to them, and stubbornly refuse to concede. This method works best in straightforward transactions. When purchasing a new car, for example, the buyer requests a lowball price, the dealer responds with a higher one, and both sides volley back and forth until finally agreeing on a number somewhere in the middle. Everyone walks away relatively happy.

Positional bargaining falls short, however, when issues of identity are at stake. Identity implicates indivisible issues of meaning, memory, and narrative. To reduce identity to a tradable commodity that can be compromised is to undermine its very essence. For almost anyone, such existential compromise would seem repugnant. Imagine two leaders negotiating a sacred piece of land:

Politician A: If you sacrifice 20 percent of your religious values, we'll give you 20 percent more land.

Politician B: I will never agree to that! I suggest we do an even 10 percent sacrifice on religious values. You add a 20 percent increase in respect for my people, and we will guarantee a 5 percent decrease in humiliation of your people for two years.