HBR Guide to Emotional IntelligenceSECTION ONE: What Is Emotional Intelligence?

Ch 1. Leading by Feel

Definitions and reflections from experts. 1. Be Realistic From a scientific standpoint, emotional intelligence is the ability to accurately perceive your own and others’ emotions; to understand the signals that emotions send about relationships; and to manage your own and others’ emotions. 2. Never Stop Learning 5 COMPONENTS OF EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE: In 1998, in what has become one of HBR’s most enduring articles, “What Makes a Leader?” Daniel Goleman introduced a framework of five components of emotional intelligence that allow individuals to recognize, connect with, and learn from their own and other people’s mental states, as well as their hallmarks. While there are many frameworks offering varying sets of EI competencies (and other models that conceive of emotional intelligence not as a set of competencies but rather as the ability to abstract and problem solve in the emotional domain), Goleman’s approach, outlined in exhibit 1, can be a helpful way to start building an understanding of emotional intelligence: 3. Get Motivated People can develop their emotional intelligence if they really want to. 4. Train the Gifted Emotional intelligence can be learned, to a degree. It’s like mathematical or musical ability. Can you become a musician if you lack natural aptitude? Yes, you can, if you take lessons and practice enough. But will you ever be a Mozart? Probably not. In the same way, emotional intelligence develops through a combination of biological endowment and training. And people who don’t have that endowment probably won’t become deeply emotionally intelligent just through training. Trying to drum emotional intelligence into someone with no aptitude for it is an exercise in futility. I believe the best way to get emotionally intelligent leaders is to select for people who already show the basic qualities you want. Think about it: That’s how athletic coaches operate. They don’t just work with anyone who wants to play a sport; they train the naturally gifted. Business managers should do the same. 5. Seek Frank Feedback Of all a leader’s competencies, emotional and otherwise, self-awareness is the most important. Without it, you can’t identify the impact you have on others. Self-awareness is very important for me as CEO. At my level, few people are willing to tell me the things that are hardest to hear. We have a CEO advisory counsel—ten people chosen each year from Avon offices throughout the world—and they tell me the good, the bad, and the ugly about the company. Anything can be said. It helps keep me connected to what people really think and how my actions affect them. 6. Engage Your Demons American history suggests not only that emotional intelligence is an indispensable ingredient of political leadership but also that it can be enhanced through sustained effort. George Washington had to work hard to control his fiery temper before he became a role model for the republic, and Abraham Lincoln had to overcome deep melancholia to display the brave and warm countenance that made him a magnet for others. Franklin Delano Roosevelt provides an even more graphic example: In his early adult years, FDR seemed carefree and condescending. Then, at 39, he was stricken with polio. By most accounts, he transformed himself over the next seven years of struggle into a leader of empathy, patience, and keen self-awareness. Richard Nixon thought he might transform himself through his own years in the wilderness, and he did make progress. But he could never fully control his demons, and they eventually brought him down. Bill Clinton, too, struggled for self-mastery and made progress, but he could not fully close the cracks in his character, and he paid a stiff price. Not all people succeed, then, in achieving self-awareness and self-control. What we have been told since the time of the Greeks is that every leader must try to control his own passions before he can hope to command the passions of others. 7. Find Your Voice Authentic leadership begins with self-awareness, or knowing yourself deeply. Self-awareness and other emotional intelligence skills come naturally to some, less so to others—but these skills can be learned. One of the useful techniques in gaining deeper self-awareness is meditation. 8. Know the Score A conductor’s authority rests on two things: the orchestra’s confidence in the conductor’s insightful knowledge of the whole score; and the orchestra’s faith in the conductor’s good heart, which seeks to inspire everyone to make music that is excellent, generous, and sincere. 9. Keep It Honest Keep it honest with friends, family and colleagues. 10. Go for the Gemba Self-awareness, self-control, empathy, humility, and other such emotional intelligence traits are particularly important in Asia. They are part of our Confucian emphasis on wah, or social harmony. When books on emotional intelligence were first translated into Japanese, people said, “We already know that. We’re actually trying to get beyond that.” We’ve been so focused on wah that we’ve built up a supersensitive structure of social niceties, where everyone seeks consensus. In the Japanese hierarchy, everyone knows his or her place, so no one is ever humiliated. This social super-sensitivity—itself a form of emotional intelligence—can lead people to shy away from conflict. But conflict is often the only way to get to the Gemba—the front line, where the action really is, where the truth lies. Thus, effective management often depends not on coolly and expertly resolving conflict—or simply avoiding it—but on embracing it at the Gemba. Japan’s most effective leaders do both. The best example is Nissan’s Carlos Ghosn. He not only had the social skills to listen to people and win them over to his ideas, but he also dared to lift the lid on the corporate hierarchy and encourage people at all levels of the organization to offer suggestions to operational, organizational, and even interpersonal problems—even if that created conflict. People were no longer suppressed, so solutions to the company’s problems bubbled up. 11. Balance the Load Emotional intelligence is powerful—which is precisely why it can be dangerous. For example, empathy is an extraordinary relationship-building tool, but it must be used skillfully or it can do serious damage to the person doing the empathizing. 12. Question Authority Emotional intelligence is necessary for leadership but not sufficient. Many people have some degree of emotional intelligence and can indeed empathize with and rouse followers; a few of them can even generate great charismatic authority. But I would argue that if they are using emotional intelligence solely to gain formal or informal authority, that’s not leadership at all. They are using their emotional intelligence to grasp what people want, only to pander to those desires in order to gain authority and influence. Easy answers sell. Leadership couples emotional intelligence with the courage to raise the tough questions, challenge people’s assumptions about strategy and operations—and risk losing their goodwill. It demands a commitment to serving others; skill at diagnostic, strategic, and tactical reasoning; the guts to get beneath the surface of tough realities; and the heart to take heat and grief.Ch 2. Do You Lead with Emotional Intelligence? Quiz yourself. (BY ANNIE MCKEE)

How would you describe yourself? The images above are cropped to separate 'questions' column from 'answers' column. Without editing the table would look like this:SECTION TWO: Self-Awareness: Understand Your Emotions, Know Your Behaviors Ch 3. You Can’t Manage Emotions Without Knowing What They Really Are (BY ART MARKMAN) Don’t just try to ignore your negative feelings.

At this point, everybody knows emotional intelligence matters in the workplace. Yet there are two aspects of emotions that make it hard for people to exercise their emotional intelligence. First, most people are still not completely clear about what emotions actually are. Second, even when we understand emotions conceptually, it can still be hard to deal with our own emotional states. To tackle the first problem: While in everyday speech, emotion and feeling are often used interchangeably, psychologists distinguish between them. Emotions are interpretations of feelings. The feelings you have (what psychologists call affect) emerge from your motivational system. You generally feel good when you’re succeeding at your goals and bad when you’re not. The more deeply your motivational system is engaged with a situation, the stronger your feelings. The motivational system, however, is not that well connected to the brain regions that help you to tell stories about the world. In order to make sense of what you’re feeling, you use information about what’s going on around you to help you translate those feelings into emotions—emotions help to guide your actions by giving you explicit feedback on how well you are currently achieving the goals the motivational system has engaged. Often, that interpretation is easy. If you are crossing the street and suddenly have to leap out of the way of an oncoming car, it is clear that the strong negative feeling you are having is fear from nearly getting hit by the car. If a colleague compliments you on a job well done, it is obvious that the positive feeling you are having is pride. But things are not always so clear. You might have a bad interaction with a family member before getting to work. As the day wears on, you may interpret your negative feelings as frustration with the project you’re working on rather than lingering negative affect from the events of the morning. Many people try to power through their negative feelings rather than attempting to understand them. But this is a lost opportunity. Emotions provide valuable information about the state of your motivational system. Ignoring them is like driving around lost, not only refusing to ask for directions but refusing to consult the map or the GPS—or even to look through the windshield. You will still be moving forward, but who knows where you will end up? Conversely, paying too much attention to your feelings is also bad. That’s like staring at your road atlas without ever turning on the car: You can’t get anywhere that way. When you have negative feelings, slow down and pay some attention to what you are feeling and why you are feeling the way you are. When you find yourself stressed, anxious, or angry, take five or 10 minutes for yourself during the day. Sit alone and breathe deeply. The deep breaths help to take some of the energy or arousal out of the feelings you are having. That can help you to think more clearly. Then start to think about some of the events of your day. Pay attention to how those thoughts influence what you are feeling. Are there particular events that increase or decrease the intensity of those feelings? You may not completely understand the source of your feelings the first time you do this. Over time, you will become more adept at paying attention to when and where you start to feel bad. Of course, once you have figured out what’s bothering you, it’s time to plan a course of action. If you keep thinking about things that bother you, you run the risk of solving nothing while getting yourself more upset. Instead, use your knowledge about the source of the bad feeling to figure out how to deal with it. Finally, if you’re really upset about something, hold off on actually executing your plan until you have given yourself a chance to calm down. Responses that seemed like a good idea in the moment may seem less ideal to a cooler head. Being willing to understand your feelings will have two benefits in the long term. First, it will help you to discover some of the aspects of your life that trigger negative feelings. That is useful, because you don’t want to misinterpret your negative feelings and attribute them to something else. For example, you would like to be able to recognize when events in your personal life are spilling over into work and are causing you to feel badly about the work you do. Second, by understanding the sources of your own emotions, you will become more expert in understanding the people around you as well. We often ignore our own feelings—and then also ignore those of our colleagues. Once you can better understand what emotions are and where your own emotions come from, you’ll have a much better ability to practice emotional intelligence.Ch 4. A Vocabulary for Your Emotions (BY SUSAN DAVID) Get precise.

Dealing effectively with emotions is a key leadership skill. And naming our emotions—what psychologists call labeling—is an important first step in dealing with them effectively. But it’s harder than it sounds: Many of us struggle to identify what exactly we are feeling, and oftentimes the most obvious label isn’t actually the most accurate. There are a variety of reasons why this is so difficult: We’ve been trained to believe that strong emotions should be suppressed. We have certain (sometimes unspoken) societal and organizational rules against expressing them. Or we’ve never learned a language to accurately describe our emotions. Broaden Your Emotional Vocabulary Words matter. If you’re experiencing a strong emotion, take a moment to consider what to call it. But don’t stop there: Once you’ve identified it, try to come up with two more words that describe how you are feeling. You might be surprised at the breadth of your emotions—or that you’ve unearthed a deeper emotion buried beneath the more obvious one. Exhibit 2 shows a vocabulary list of emotion terms; you can find much more by searching Google for any one of these. It’s equally important to do this with “positive” emotions as well as “negative” ones. Being able to say that you are excited about a new job (not just “I’m nervous”) or trusting of a colleague (not just “He’s nice”), for example, will help you set your intentions for the role or the relationship in a way that is more likely to lead to success down the road. Consider the Intensity of the Emotion We’re apt to leap to basic descriptors like “angry” or “stressed” even when our feelings are far less extreme. I had a client, Ed (not his real name), who was struggling in his marriage; he frequently described his wife as “angry” and often got angry in return. But as the vocabulary chart suggests, every emotion comes in a variety of flavors. When we talked about other words for his wife’s emotions, Ed saw that there were times that she was perhaps just annoyed or impatient. This insight completely changed their relationship, because he could suddenly see that she wasn’t just angry all the time—and so could actually respond to her specific emotion and concern without getting angry himself. Similarly, it matters in your own self-assessment whether you are angry or just grumpy, mournful or just dismayed, elated or just pleased. As you label your emotions, also rate them on a scale of 1–10. How deeply are you feeling the emotion? How urgent is it, or how strong? Does that make you choose a different set of words? Write It Out James Pennebaker has done 40 years of research into the links between writing and emotional processing. His experiments revealed that people who write about emotionally charged episodes experience a marked increase in their physical and mental well-being. Moreover, in a study of recently laid-off workers, he found that those who delved into their feelings of humiliation, anger, anxiety, and relationship difficulties were three times more likely to have been reemployed than those in control groups. These experiments also revealed that over time those who wrote about their feelings began to develop insights into what those feelings meant (or didn’t mean!), using phrases such as “I have learned...”; “It struck me that... ”; “The reason that...”; “I now realize...”; and “I understand...” The process of writing allowed them to gain a new perspective on their emotions and to understand them and their implications more clearly. Here’s an exercise you can use to reflect through writing. You could do this every day, but it’s particularly important when you’re going through a tough time or a big transition, or if you’re feeling emotional turmoil. • Set a timer for 20 minutes. • Using either a notebook or computer, write about your emotional experiences from the past week, month, or year. • Don’t worry about making it perfect or readable; go where your mind takes you. • At the end, you don’t have to save the document; the point is that those thoughts are now out of you and on the page. You can also use these three approaches—broadening your vocabulary, noting the intensity of an emotion, and writing it out—when trying to better understand another person’s emotions. As we saw with the example of Ed and his wife, we are just as likely to mislabel someone else’s emotions as our own, with similarly complicating consequences. By understanding what they are feeling more precisely, you will be better equipped to respond in a constructive way. Once you understand what you are feeling, then you can better address and learn from those more accurately described emotions.Ch 5. Are You Sure You Show Respect? (BY CHRISTINE PORATH) No other leadership behavior has a bigger effect on employees.

There are times when leaders know that showing respect is critical, but many struggle to demonstrate it. If you’re one of those leaders, consider the following steps: % Ask for focused feedback on your best behaviors % Discover your shortcomings: Gather candid feedback from your colleagues and friends not only on what you’re doing that conveys respect, but also on how you can improve. Specifically, what are your shortcomings? % Work with a coach % Ask, specifically, how you can improve Once you have clarity on which behaviors you want to improve, gather information from others about how best to go about this. This “feedforward” method, originated by author Marshall Goldsmith, is a terrific way to gather specific ideas for improving your behavior. The process consists of five steps: 1. Describe your goal clearly and simply to anyone you know. 2. Ask for two suggestions. Encourage creative ideas. 3. Listen carefully. Write the suggestions down. 4. Respond with “thank you.” Nothing more. No excuses or defensiveness. 5. Repeat by asking additional people. % Enlist your team in keeping you accountable: Choose one change that could improve your behavior and then experiment, asking your team to help you by letting you know when they see improvement. % Make time for reflection: Keep a journal to provide insight into when/where/why you are your best and when you are uncivil. Identify situations that cause you to lose your temper. % Consider tracking your own energy through the day via an energy audit tool, such as “Energy Audit—Awareness and Action,” which is available from the University of Michigan. The energy audit is available at http://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/GrantSpreitzer-EnergyAudit.pdfSECTION THREE: Manage Your Emotions Ch 6. Make Your Emotions Work for You (BY SUSAN DAVID) Use them as data.

We often hear tips and tricks for helping us to “control” our emotions, but that’s the wrong idea. Strong emotions aren’t bad; they don’t need to be pushed down or controlled; they are, in fact, data. Our emotions evolved as a signaling system, a way to help us communicate with each other and to better understand ourselves. What we need to do is learn to develop emotional agility, the capacity to mine even the most difficult emotions for data that can help us make better decisions. What’s the Function of the Emotion? To make the most of that data, ask yourself what the function of your emotion is. What is it telling you? What is it trying to signal? Is Your Reaction Aligned with Your Values? Our emotions can also help us understand our deepest values. They can often signal what is more important to us: You feel love for your family. You feel ambition at work and appreciate achievement and self-worth. You feel fulfilled when you’ve been able to help a direct report achieve their goals. You feel peace and satisfaction on a mountain summit. It’s far better to focus on these deeper values rather than your immediate emotions, which can spur poor decisions. Managing emotions isn’t just doing away with them; it’s putting strategies in place that let you use them effectively rather than letting them govern your behaviors and actions. Your emotions are your natural guidance system—and they are more effective when you don’t try to fight them.Ch 7. Defuse a Challenging Interaction Reframe negative thoughts and neutralize bad behavior.

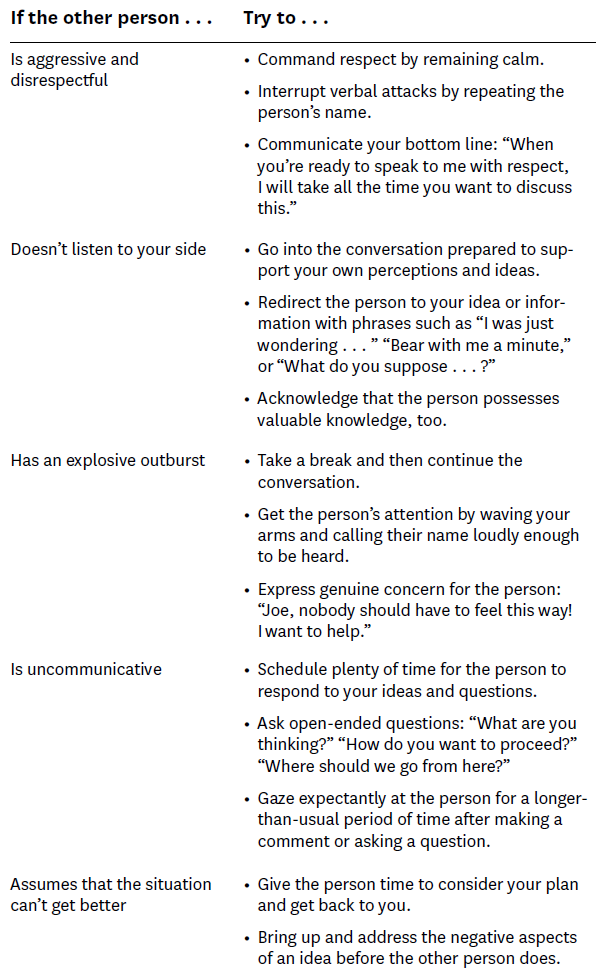

Conflicts stir up many emotions, especially negative thoughts and feelings. To successfully manage these disagreements in the moment, you need to address your own emotions as well as those of the other person. Reframe Negative Thoughts During difficult interactions, you may begin to question your perceptions about yourself. For example, suppose a direct report says, “I didn’t attend the meeting because I didn’t think you valued my ideas.” In response, you wonder to yourself, “Maybe I’m not a competent manager after all.” For many people, the sense that their self-image is being challenged creates intense emotions. These feelings can become overwhelming, making it virtually impossible to converse productively about any subject. To experience —and then let go of— difficult feelings: • Focus on the other person’s intentions and on the facts. If you discover that your employee had legitimate reasons for not showing up at a weekly meeting, your annoyance may fade away. • Examine your contributions to the problem. If you realize that you’ve accidentally advised an employee to focus on an unnecessary task, your frustration may dissipate. • Question your assumptions. If you find your belief that a colleague doesn’t value product quality is mistaken, you may feel less anger over her tendency to take shortcuts. Your goal in reframing negative thoughts is to be able to express your complete range of emotions without judging or blaming the other person. Neutralize Unproductive Behaviors Although you can work to manage your own reactions, you can’t control those of the other person in the conflict. Try the techniques in exhibit 3 for dealing with unproductive behaviors:Ch 8. Stay Grounded in Stressful Moments (BY LEAH WEISS) Use your body to take a break from your mind’s chatter.

Mindfulness should be as much a physical practice as it is a mental one. Given its name, you might think mindfulness is something you do only with your mind. In fact, lots of research, including my own, has shown that paying attention to our bodies is often an easy way into mindfulness and helps us reduce stress while it’s happening. This may seem counterintuitive because when our mind is overwhelmed, our body is often the last thing we’re thinking about. If we notice our bodies at all in moments of stress, most likely it is as they interrupt our normal activities: carpal tunnel syndrome, back pain, breast pumping, dental appointments, sore feet, sick days, or simply the routine hunger that forces us to stop what we’re doing multiple times a day and eat. Yet if we focus our attention on our bodies, they can be our anchor in what’s happening right now, even if the sensations are unpleasant. This is how anchoring works: We bring our attention into our bodies, noticing—rather than avoiding—the tension, circulation, pain, pleasure, or just neutral physical experience of, say, our right shoulder or the arch of our left foot. This practice helps us snap back to reality. In fact, our bodies are the quickest, surest way back to the present moment when our minds are lost in rehashing the past or rehearsing the future. We cause ourselves a lot of unnecessary suffering when our minds aren’t paying attention. The amygdala, located in the brain’s medial temporal lobe, is the part of the brain that detects and processes fear. When our amygdala is activated by a situation that is interpreted as a potential threat, even if we are just reading an unpleasant email, it initiates physiological changes such as increased muscle tension and accelerated breathing. This association becomes so strong that we take the body’s reaction as evidence of danger, just as Pavlov’s dogs took the sound of the bell as evidence of dinner. As a result, a vicious cycle can develop wherein the increased muscle tension and rapid breathing caused by an activated amygdala further activates the amygdala. Thankfully, we can use anchoring to break out of it. Here are some simple, effective anchoring practices you can use: • Take a single breath. It takes just one intentional breath to change our perspective. A single breath gives you a break from the mind’s chatter and a chance for your body to regulate after amping up in response to a perceived threat. Most of the time, when you’re in distress, you’re in the middle of telling yourself a story and you fully believe it. A breath can take you out of the story, making you less gullible. You can follow the breath into your body, where you gain just enough distance to judge whether your head is with you (in line with your current intentions and greater purpose) or against you, and then consciously choose which way you want to go. • Pay attention to emotions. Another reason to anchor in your body is that it’s where you feel your emotions, which are important to acknowledge even if they may seem like a liability, especially at work. I’ve studied the downsides of emotional suppression and I can assure you—it’s not beneficial. It’s paradoxical, but nonjudgmentally engaging with negative emotions negatively correlates with negative emotions and mood disorder. In other words, if you acknowledge and recognize unpleasant emotions, they have less power to cause you distress. In one study, participants wrote every day for four days about either a traumatic experience or a neutral event. Those who wrote about trauma made fewer health center visits in the following six months than those who wrote about a neutral event. When you pay attention to your body, you can catch emotional information upstream, before it hijacks your whole system—once it does, it’s too late to use it to your advantage. • Remember that your colleagues have bodies too. Annoyed with your boss? Think you can’t last another day with an impossible colleague? If you let it, your body can connect you to other people— even difficult ones—since the body is a major fundamental part of what we have in common. This sounds obvious, but the implications are profound. Our bodies and the pleasure and pain that come with them—their attendant aches and illnesses, their needs and indignities, the impossibility of choosing the one we want, the fear of losing it someday, and the ways we fight our bodies or pretend they don’t exist—are shared experiences. When you ignore your body (or try to), you miss out on a part of what we have in common. The empathy gained from this awareness helps you to have productive professional relationships, rather than suffering from ongoing frustration and pain. • Magnify little pleasures. Don’t underestimate the joy of taking that first sip of afternoon coffee. It’s human nature to notice pain more than pleasure, but with reminders and practice you can experience joy throughout the day in the simple, reliable pleasures of having a body. It might be from sitting when you’ve been standing for too long, or standing up and stretching when you’ve been sitting; holding a new pen with a particularly cushy, ergonomic grip; laughing hard when something’s funny; eating when you’re hungry; the relative quiet of the office after a morning with screaming kids; slipping out of uncomfortable shoes under your desk. Every day, no matter how lousy, affords countless opportunities like these to feel good. Recently, I had a meeting at the VA hospital in Palo Alto and came across two veterans as I was walking. They were sitting in front of the building, both in wheelchairs. One man leaned over to his companion and said, “Well, it’s great that we can move our hands.” The other responded, “Yes, you are right. That is great!” Their perspective provides a powerful reminder that most of us can, if we choose, find within our daily routine a small joy worthy of being celebrated.Ch 9. Recovering from an Emotional Outburst (BY SUSAN DAVID) You can’t just apologize and move on.

It happens—we all get emotional at work. You might scream, or cry, or pound the table and stamp your feet. This is not ideal office behavior, of course, and there are ramifications to these outbursts, but they don’t have to be career-killers either. If you take a close look at what happened, why you acted the way you did, and take steps to remedy the situation, you can turn an outburst into an opportunity. If you tend to suppress your emotions, you’re likely to just ignore your tantrum and move on. If you are prone to ruminating over your mistakes, you’ll overthink your outburst and beat yourself up about it. Neither of these strategies is productive; they don’t help you solve the problem or promote your own wellbeing. Instead, treat your outburst for what it is: data. A key emotional intelligence skill is being able to manage your emotion, but you can’t manage what you can’t recognize and understand. So first, be open to emotions. What was I feeling here? Emotions are signals, beacons that show you that you care about something. To recognize your emotions, you have to be able to differentiate between feelings—sadness, anger, frustration (see chapter 4 in this guide). In many work environments, people suffer from what psychologists call alexithymia—a dispositional difficulty in accurately labeling and expressing what they’re feeling. These people tend to be vague about their emotions. So a manager will say to herself, for example, “Gee, I yelled because I was really stressed out.” But that gives her no information about what was really going on. Once you’ve recognized the emotion—fear, disappointment, anger—your next step is to understand what, exactly, caused it: “Why is it that I reacted in this particular way?” “What was happening in this situation that I found upsetting?” “What values of mine may have been transgressed or challenged?” For example, maybe you lost it and screamed at a colleague when you found out that your project was cut. If you dig deeper, you may find that it wasn’t exactly about the project but rather how the decision was made—that you didn’t feel it was made fairly. The research on emotions shows that there are general triggers that you should be aware of. When your outburst is anger—yelling, stomping your feet—it’s typically because you’re frustrated or feel thwarted. You’ve been stopped from doing something that’s important to you. When you feel sadness or cry, it’s usually because of a loss. Acting out on anxiety is prompted by a sense of threat. It’s helpful to think about these universal triggers, and then ask, “What is it specifically that was important to me in this situation?” Once you’ve recognized how you feel, and why you feel it, you can focus on what to do to make things better—to manage the situation. It goes without saying that you should apologize if you yelled or lost your cool, but that’s not enough. Your goal isn’t just to repair the relationship, but to strengthen it. After you’ve calmed down and you return to your team the following day or week, instead of saying, “Gee, I’m so sorry about what I did; now let’s move on,” address what really happened for you. You might say something like, “I got really mad and I’m not proud of my behavior. I’ve been thinking long and hard about what it was that I found so upsetting and I’ve realized that my sense of fairness was challenged because of how the defunding decisions were made.” There’s research that shows that when you appropriately disclose your emotions in this way, people are more likely to treat you with compassion and forgiveness than if you had just offered an apology. From there you start a shared conversation about what’s important to each of you and how you can work better together. No one wants to earn a reputation as a crier or a screamer at work. Instead of running and hiding or wallowing in self-pity when you’ve lost it, bring a good dose of compassion and curiosity to the situation. To be kind and compassionate toward yourself—especially in the moments you are least proud of—is not the same as letting yourself off the hook. In fact, studies show that people who are self-compassionate are much more likely to hold themselves to high standards and work to make things right. And treating yourself that way is more likely to inspire others to do the same.SECTION FOUR: Everyday Emotional Intelligence Ch 10. Writing Resonant Emails (BY ANDREW BRODSKY) Human communication for the digital age.

Imagine sending a detailed question to your boss and getting a one-word response: “No.” Is she angry? Offended by your email? Or just very busy? When I conduct research with organizations on the topic of communication, one of the most common themes raised by both employees and managers is the challenge of trying to communicate emotional or sensitive issues over email. Email, of course, lacks most normal cues for relaying emotion, such as tone of voice and facial expressions. But in many cases, using email is simply unavoidable. So how can you balance the need to communicate with avoiding the potential pitfalls of using emotion in email? Here are three concrete, research-based recommendations: 1. Understand what drives how emails are interpreted It is clear that people often misinterpret emotion in email, but what drives the direction of the misinterpretation? For one, people infuse their emotional expectations into how they read messages, regardless of the sender’s actual intent.1 Consider the email, “Good job on the current draft, but I think we can continue to improve it.” Coming from a peer, this email will seem very collaborative; coming from a supervisor, it may seem critical. In addition to relative position (emails from people high in power tend to be perceived as more negative), there are other contextual factors to consider: the length of a relationship (emails from people we know well tend to be perceived as less negative), the emotional history of the relationship, and the individual’s personality (negative people tend to perceive messages as more negative). The first step in avoiding miscommunication is to try to stand in the recipient’s shoes, and imagine how they are likely to interpret your message. Doing so can help you to prevent misunderstandings before they ever occur. 2. Mimic behaviors What is the best way to convey emotions via email? Emoticons? Word choice? Exclamation points? There is no single correct answer; the proper cues will vary based on the context. For instance, you likely wouldn’t want to send a smiley face emoticon to a client organization that is known for having a very formal culture. Alternatively, you wouldn’t want to send an overly formal email to a very close colleague. One strategy that has been found to be very effective across settings is to engage in behavioral mimicry—using emoticons, word-choice, and slang/jargon in a similar manner to the person with whom you are communicating. In a set of studies of American, Dutch, and Thai negotiators, using behavioral mimicry in the early stages of text-based chat negotiations increased individual outcomes by 30%. This process of mimicry increases trust because people tend to feel an affinity toward those who act similarly to them. 3. State your emotions While mimicking behaviors can be effective, it is still a rather subtle strategy that leaves the potential for emotional ambiguity. The simplest solution to avoid any confusion is to just explicitly state the emotion that you want to relay in your email. One excellent example of how this works comes from a media organization I recently worked with. I asked employees for an email that they felt was written very poorly, and one employee provided me with the following message from a manager: The intro of the commercial needs to be redone. I’m sure that’s the client’s doing and you will handle it :). Warm Regards, [Manager’s Name]. To me as an outsider (and I’m guessing to the manager as well), this email seemed well crafted to avoid offending the employee. However, the employee felt differently and explained: “She knows perfectly well that I made the terrible intro, and she was saying, ‘Well, I’m sure the client made that segment and that you will tackle it,’ and then she put a little smiley face at the end. So overall, a condescendingly nasty tone.” If the manager had avoided subtlety and stated her meaning directly, there might have been less room for interpretation. For example, what if she had written: I am very happy with your work so far. I think the intro could be improved, though; would you mind giving it another shot? The employee would have had far less ambiguity to fill in with her own emotional expectations. Yet people rarely state their intended emotions, even when the stakes are high. Research from NYU has shown that many people are overconfident in their ability to accurately relay emotions when it comes to email. It may seem obvious to the message sender that a coworker who never takes sick days will realize a comment about them leaving early is humorous rather than serious. However, that coworker might be particularly concerned about being seen as lazy and will feel hurt or offended. Given the constantly evolving nature of organizational communication, there is still a lot to learn about effective email use. However, there are some clear areas where we can improve. In reality, we all have the same flaw: We tend to be overly focused on ourselves and our own goals, while failing to amply account for other people’s perspectives. Using these methods for bridging your and your email recipient’s perspectives, by both increasing message clarity and building trust, will help you to ensure effective communication.Ch 11. Running Powerful Meetings (BY ANNIE MCKEE) Use empathy to understand potential conflicts.

If you want to improve how people work together at meetings, you’ll need two key emotional intelligence competencies: empathy and emotional self-management. Why empathy? Empathy is a competency that allows you to read people. Who is supporting whom? Who is pissed off, and who is coasting? Where is the resistance? This isn’t as easy as it seems. Sometimes, the smartest resisters often look like supporters, but they’re not supportive at all. They’re smart, sneaky idea killers. Carefully reading people will also help you understand the major and often hidden conflicts in the group. Hint: These conflicts probably have nothing to do with the topics discussed or decisions being made at the meeting. They are far more likely to be linked to very human dynamics like who is allowed to influence whom (headquarters versus the field, expats versus local nationals) and power dynamics between genders and among people of various races. Empathy lets you see and manage these power dynamics. Many of us would like to think that these sorts of concerns—and office politics in general—are beneath us, unimportant, or just for those Machiavellian folks we all dislike. Realistically, though, power is hugely important in groups because it is the real currency in most organizations. And it plays out in meetings. Learning to read how the flow of power is moving and shifting can help you lead the meeting—and everything else. Keep in mind that employing empathy will help you understand how people are responding to you. As a leader you may be the most powerful person at the meeting. Some people, the dependent types, will defer at every turn. That feels good, for a minute. Carry on that way, and you’re likely to create a dependent group—or one that is polarized between those who will do anything you want and those who will not. This is where emotional self-management comes in, for a couple of reasons. First: Take a look at the dependent folks in your meetings. Again, it can feel really good to have people admire you and agree with your every word. In fact, this can be a huge relief in our conflict-ridden organizations. But again, if you don’t manage your response, you will make group dynamics worse. You will also look like a fool. Others are reading the group, too, and they will rightly read that you like it when people go along with you. They will see that you are falling prey to your own ego or to those who want to please or manipulate you. Second: Strong emotions set the tone for the entire group. We take our cue from one another about how to feel about what’s going on around us. Are we in danger? Is there cause for celebration? Should we be fed up and cynical or hopeful and committed? Here’s why this matters in meetings: If you, as a leader, effectively project out your more positive emotions, such as hope and enthusiasm, others will “mirror” these feelings and the general tone of the group will be marked by optimism and a sense of “we’re in this together, and we can do it.” And there is a strong neurological link between feelings and cognition. We think more clearly and more creatively when our feelings are largely positive and when we are appropriately challenged, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote in his classic Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. The other side of the coin is obvious. Your negative emotions are also contagious, and they are almost always destructive if unchecked and unmanaged. Express anger, contempt, or disrespect, and you will definitely push people into fight mode—individually and collectively. Express disdain, and you’ll alienate people far beyond the end of the meeting. And it doesn’t matter who you feel this way about. All it takes is for people to see it, and they will catch it—and worry that next time your target will be them. This is not to say that all positive emotions are good all the time or that you should never express negative emotions. The point is that the leader’s emotions are highly infectious. Know this and manage your feelings accordingly to create the kind of environment where people can work together to make decisions and get things done. It may go without saying, but you can’t do any of this with your phone on. As Daniel Goleman shares in his book Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence, we are not nearly as good at multitasking as we think we are. Actually we stink at it. So turn it off and pay attention to the people you are with today. In the end, it’s your job to make sure people leave your meeting feeling pretty good about what’s happened, their contributions, and you as the leader. Empathy allows you to read what’s going on, and self-management helps you move the group to a mood that supports getting things done—and happiness.Ch 12. Giving Difficult Feedback (BY MONIQUE VALCOUR) Spark growth rather than frustration.

Powerful, high-impact feedback conversations share the following elements: 1. An intention to help the employee grow, rather than to show him he was wrong. The feedback should increase, not drain, the employee’s motivation and resources for change. When preparing for a feedback conversation as a manager, reflect on what you hope to achieve and on what impact you’d like to have on the employee, perhaps by doing a short meditation just before the meeting. 2. Openness on the part of the feedback giver, which is essential to creating a high-quality connection that facilitates change. If you start off feeling uncomfortable and self-protective, your employee will match that energy, and you’ll each leave the conversation frustrated with the other person. 3. Inviting the employee into the problem-solving process. You can ask questions such as: What ideas do you have? What are you taking away from this conversation? What steps will you take, by when, and how will I know?Ch 13. Making Smart Decisions (BY ANDREW CAMPBELL, JO WHITEHEAD, AND SYDNEY FINKELSTEIN) Emotional tagging both helps and hinders our ability to choose.

IDEA IN BRIEF • Leaders make decisions largely through unconscious processes that neuroscientists call pattern recognition and emotional tagging. These processes usually make for quick, effective decisions, but they can be distorted by bias. • Managers need to find systematic ways to recognize the sources of bias—what the authors call “red flag conditions”—and then design safeguards that introduce more analysis, greater debate, or stronger governance. The authors identify three of these red flag conditions as the presence of: – Inappropriate self-interest, which, according to research, can bias even well-intentioned professionals such as doctors and auditors. – Distorting attachments to people, places, and things—for example, an executive’s reluctance to sell a business unit they’ve worked in. – Misleading memories, which may seem relevant and comparable to the current situation but lead our thinking down the wrong path by obscuring important differentiating factors. • By using the approach described in this article, companies will avoid many flawed decisions that are caused by the way our brains operate. IDEA IN PRACTICE Leaders make quick decisions by recognizing patterns in the situations they encounter, and then responding to the emotional associations attached to those patterns. Most of the time, the process works well, but it can result in serious mistakes when those emotional associations are biased. To guard against distorted decision making and strengthen the decision process, get the help of an independent person to identify which decision makers are likely to be affected by self-interest, emotional attachments, or misleading memories. If the risk of distorted decision making is high, build safeguards into the decision process. Expose decision makers to additional experience and analysis, design in more debate and opportunities for challenge, add more oversight, and monitor whether the decision is generating the expected results. IDENTIFYING RED FLAGS Red flags are useful only if they can be spotted before a decision is made. How can you recognize them in complex situations? We have developed the following seven-step process: 1. Lay out the range of options. It’s never possible to list them all. But it’s normally helpful to note the extremes. These provide boundaries for the decision. 2. List the main decision makers. Who is going to be influential in making the judgment calls and the final choice? There may be only one or two people involved. But there could also be 10 or more. 3. Choose one decision maker to focus on. It’s usually best to start with the most influential person. Then identify red flag conditions that might distort that individual’s thinking. Discuss with the individual if needed. 4. Check for inappropriate self-interest or distorting attachments. Is any option likely to be particularly attractive or unattractive to the decision maker because of personal interests or attachments to people, places, or things? Do any of these interests or attachments conflict with the objectives of the decision? 5. Check for misleading memories. What are the uncertainties in this decision? For each area of uncertainty, consider whether the decision maker might draw on potentially misleading memories. Think about past experiences that could mislead, especially ones with strong emotional associations. Think also about previous judgments that could now be unsound, given the current situation. 6. Repeat the analysis with the next-most influential person. In a complex case, it may be necessary to consider many more people, and the process may bring to light a long list of possible red flags. 7. Review the list of red flags you have identified for bias. Determine whether the balance of red flags is likely to bias the decision in favor of or against some options. If so, put one or more safeguards in place. Biases can cancel each other out, so it is necessary to assess the balance taking account of the likely influence of each person involved in the decision.Ch 14. An Emotional Strategy for Negotiations (BY ALISON WOOD BROOKS) How to avoid the pitfalls of anxiety and anger.

Here are coping strategies for—many of the emotions people typically feel over the course of a negotiation. Anxiety is most likely to crop up before the process begins or during its early stages. We’re prone to experience anger or excitement in the heat of the discussions. And we’re most likely to feel disappointment, sadness, or regret in the aftermath. Avoiding Anxiety Anxiety is a state of distress in reaction to threatening stimuli—in particular, novel situations that have the potential for undesirable outcomes. In contrast to anger, which motivates people to escalate conflict (the “fight” part of the fight-or-flight response), anxiety trips the “flight” switch and makes people want to exit the scene. Because patience and persistence are often desirable when negotiating, the urge to exit quickly is counterproductive. But the negative effects of feeling anxious while negotiating may go further. In my recent research, I wondered if anxious negotiators also develop low aspirations and expectations, which could lead them to make timid first offers—a behavior that directly predicts poor negotiating outcomes. In 2012, with Francesca Gino and Maurice Schweitzer, I conducted eight experiments to explore how anxious people behaved in situations in which they could seek advice from others. We found that relative to people who did not feel anxious, they were less confident, more likely to consult others when making decisions, and less able to discriminate between good and bad advice. In the most relevant of these experiments, we found that anxious participants did not discount advice from someone with a stated conflict of interest, whereas subjects feeling neutral emotions looked upon that advice skeptically. Although this research didn’t directly address how the subjects would negotiate, it suggests that people who express anxiety are more likely to be taken advantage of in a negotiation, especially if the other party senses their distress. The takeaway from both research and practice is clear: Try your utmost to avoid feeling anxious while negotiating. How can you manage that? Train, practice, rehearse, and keep sharpening your negotiating skills. Anxiety is often a response to novel stimuli, so the more familiar the stimuli, the more comfortable and the less anxious you will feel. Indeed, although many people enroll in negotiation classes to learn strategies and increase skills, one of the primary benefits is the comfort that comes from repeatedly practicing deal making in simulations and exercises. Negotiation eventually feels more routine, so it’s not such an anxiety-inducing experience. Managing Anger Like anxiety, anger is a negative emotion, but instead of being self-focused, it’s usually directed toward someone else. In most circumstances, we try to keep our tempers in check. When it comes to negotiating, however, many people believe that anger can be a productive emotion— one that will help them win a larger share of the pie. This view stems from a tendency to view negotiations in competitive terms rather than collaborative ones. Researchers call this the fixed-pie bias: People, particularly those with limited experience making deals, assume that a negotiation is a zero-sum game in which their own interests conflict directly with a counterpart’s. (More experienced negotiators, in contrast, look for ways to expand the pie through collaboration, rather than nakedly trying to snatch a bigger slice.) Anger, the thinking goes, makes one seem stronger, more powerful, and better able to succeed in this grab for value. In fact, there’s a body of research—much of it by Keith Allred, a former faculty member at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government—that documents the consequences of feeling angry while negotiating. This research shows that anger often harms the process by escalating conflict, biasing perceptions, and making impasses more likely. It also reduces joint gains, decreases cooperation, intensifies competitive behavior, and increases the rate at which offers are rejected. Angry negotiators are less accurate than neutral negotiators both in recalling their own interests and in judging other parties’ interests. And angry negotiators may seek to harm or retaliate against their counterparts, even though a more cooperative approach might increase the value that both sides can claim from the negotiation. Tamping down any anger you feel—and limiting the anger you express—is a smarter strategy. This may be hard to do, but there are tactics that can help. PREPARING YOUR EMOTIONAL STRATEGY Preparation is key to success in negotiations. It’s vital to give advance thought to the objective factors involved (Who are the parties? What are the issues? What is my best outside option if we don’t reach a deal?), but it is perhaps even more important to prepare your emotional strategy. Use the following questions and tips to plan ahead for each stage of the negotiation. Building rapport before, during, and after a negotiation can reduce the odds that the other party will become angry. If you seek to frame the negotiation cooperatively— to make it clear that you’re seeking a win-win solution instead of trying to get the lion’s share of a fixed pie—you may limit the other party’s perception that an angry grab for value will work well. If the other party does become angry, apologize. Seek to soothe. Even if you feel that his anger is unwarranted, recognize that you’re almost certainly better positioned tactically if you can reduce the hostility. Perhaps the most effective way to deal with anger in negotiations is to recognize that many negotiations don’t unfold all at once but take place over multiple meetings. So if tensions are flaring, ask for a break, cool off, and regroup. This isn’t easy when you’re angry, because your fight-or-flight response urges you to escalate, not pull back. Resist that urge and give the anger time to dissipate. In heated negotiations, hitting the pause button can be the smartest play. Finally, you might consider reframing anger as sadness. Though reframing one negative emotion as another sounds illogical, shared feelings of sadness can lead to cooperative concession making, whereas oppositional anger often leads to an impasse. Handling Disappointment and Regret It can be tempting to see negotiations in binary terms— you either win or lose. Of course, that is generally too simplistic: Most complex negotiations will end with each side having achieved some of its goals and not others— a mix of wins and losses. Still, as a negotiation winds down, it’s natural to look at the nascent agreement and feel, on balance, more positive or negative about it. Disappointment can be a powerful force when it’s expressed to the other party near the end of the negotiation. There’s a relationship between anger and disappointment— both typically arise when an individual feels wronged—and it’s useful to understand how one can be used more constructively than the other. (Think back to how you reacted as a child if your parents said “I’m very disappointed in you” instead of “I’m very angry with you.”) Although expressing anger may create defensiveness or increase the odds of a standoff, expressing disappointment can serve a more tactical purpose by encouraging the other party to look critically at her own actions and consider whether she wants to change her position to reduce the negative feelings she’s caused you. Research shows that one cause of disappointment in a negotiation is the speed of the process. When a negotiation unfolds or concludes too quickly, participants tend to feel dissatisfied. They wonder if they could or should have done more or pushed harder. Negotiation teachers see this in class exercises: Often the first students to finish up are the most disappointed by the outcome. The obvious way to lessen the likelihood of disappointment is to proceed slowly and deliberately. Regret is slightly different from disappointment. While the latter tends to involve sadness about an outcome, someone feeling regret is looking a little more upstream, at the course of actions that led to this unhappy outcome, and thinking about the missteps or mistakes that created the disappointment. Studies show that people are most likely to regret actions they didn’t take—the missed opportunities and errors of omission, rather than errors of commission. That can be a powerful insight for negotiators, whose primary actions should be asking questions, listening, proposing solutions, and brainstorming new alternatives if the parties can’t agree. Ironically, people often don’t ask questions while negotiating: They may forget to raise important matters or feel reluctant to probe too deeply, deeming it invasive or rude. Those fears are often misplaced. In fact, people who ask a lot of questions tend to be better liked, and they learn more things. In negotiations, information is king and learning should be a central goal. One way to reduce the potential for regret is to ask questions without hesitation. Aim to come away from the negotiation with the sense that every avenue was explored. Skilled negotiators use another technique to minimize the odds of regret: the post-settlement settlement. This strategy recognizes that tension often dissipates when there’s a deal on the table that makes everyone happy, and sometimes the best negotiating happens after that tension is released. So instead of shaking hands and ending the deal making, one party might say, “We’re good. We have terms we can all live with. But now that we know we’ve reached an agreement, let’s spend a few more minutes chatting to see if we can find anything that sweetens it for both sides.” Done ineptly, this might seem as if one party is trying to renege or renegotiate. However, when handled deftly, a post-settlement settlement can open a pathway for both sides to become even more satisfied with the outcome and stave off regrets. Tempering Happiness and Excitement There isn’t much research on how happiness and excitement affect negotiations, but intuition and experience suggest that expressing these emotions can have significant consequences. The National Football League prohibits and penalizes “excessive celebrations” after a touchdown or big play because such conduct can generate ill will. For the same reason, the “winner” in a deal should not gloat as the negotiations wrap up. Nonetheless, this happens all the time. In workshops, I routinely see students unabashedly boast and brag (sometimes to the entire class) about how they really stuck it to their opponents in a negotiation exercise. Not only do these students risk looking like jerks, but in a real-world setting, they might suffer more dire consequences: the other party might invoke a right of rescission, seek to renegotiate, or take punitive action the next time the parties need to strike a deal. Although it’s unpleasant to feel disappointed after a negotiation, it can be even worse to make your counterparts feel that way. And in certain situations, showing happiness or excitement triggers disappointment in others. The best negotiators achieve great deals for themselves but leave their opponents believing that they, too, did fabulously, even if the truth is different. In deals that involve a significant degree of future collaboration—say, when two companies agree to merge, or when an actor signs a contract with a producer to star in an upcoming movie—it can be appropriate to show excitement, but it’s important to focus on the opportunities ahead rather than the favorable terms one party just gained. Another danger of excitement is that it may increase your commitment to strategies or courses of action that you’d be better off abandoning. In my negotiation class, we do an exercise in which students must decide whether or not to send a race car driver into an important race with a faulty engine. Despite the risks, most students opt to go ahead with the race because they are excited and want to maximize their winnings. The exercise has parallels to a real-life example: the launch of the Challenger space shuttle. Though the engineers who designed the Challenger’s faulty O-ring had qualms about it, NASA managers were overly excited and determined to proceed with the launch. Their decision ultimately led to the craft’s explosion and the loss of its seven crew members. There are two lessons for negotiators here. First, be considerate: Do not let your excitement make your counterparts feel that they lost. Second, be skeptical: Do not let your excitement lead to overconfidence or an escalation of commitment with insufficient data. Negotiating requires some of the same skills that playing poker does—a strategic focus, the imagination to see alternatives, and a knack for assessing odds, reading people, understanding others’ positions, and bluffing when necessary. However, whereas the parties in a negotiation must strive for agreement, poker players make decisions unilaterally. Poker also lacks win-win outcomes or pie-sharing strategies: Any given hand is generally a zero-sum game, with one player’s gains coming directly from the other players’ pots. Nonetheless, negotiators can learn a crucial lesson from the card table: the value of controlling the emotions we feel and especially those we reveal. In other words, good negotiators need to develop a poker face— not one that remains expressionless, always hiding true feelings, but one that displays the right emotions at the right times. And although all human beings experience emotions, the frequency and intensity with which we do so differs from person to person. To be a better deal maker, conduct a thorough assessment of which emotions you are particularly prone to feel before, during, and after negotiations, and use techniques to minimize (or maximize) the experience and suppress (or emphasize) the expression of emotions as needed. In one of my favorite scenes from the TV show 30 Rock, hard-driving CEO Jack Donaghy (Alec Baldwin), who fancies himself an expert negotiator, explains to a colleague why he struck a poor deal: “I lost because of emotion, which I always thought was a weakness, but now I have learned can also be a weapon.” Borrowing Jack’s insightful metaphor, I urge you to wield your emotions thoughtfully. Think carefully about when to draw these weapons, when to shoot, and when to keep them safely tucked away in a hidden holster. Try to avoid feeling anxious, be careful about expressing anger, ask questions to circumvent disappointment and regret, and remember that happiness and excitement can have adverse consequences. Just as you prepare your tactical and strategic moves before a negotiation, you should invest effort in preparing your emotional approach. It will be time well spent. MANAGING YOUR COUNTERPART’S EMOTIONS Negotiating is an interpersonal process. There will always be at least one other party (and often many more) involved. In the adjoining article, I discuss how to manage your own emotions during a negotiation. But what about the other people at the table? Can you manage their emotions as well? I suggest two strategies for doing so: 1. Be observant. Perceiving how other people are feeling is a critical component of emotional intelligence, and it’s particularly key in negotiations (as Adam Galinsky and his colleagues have found). So tune in to your counterpart’s body language, tone of voice, and choice of words. When her verbal and nonverbal cues don’t match up, ask questions. For example, “You are telling me you like this outcome, but you seem uneasy. Is something making you uncomfortable?” Or “You say you’re angry, but you seem somewhat pleased. Are you truly upset about something? Or are you trying to intimidate me?” Asking specific questions based on your perceptions of the other party’s emotional expressions will make it easier for you to understand her perspective (a task people are shockingly bad at, according to research by Nicholas Epley). It will also make it difficult for a counterpart to lie to you; evidence suggests that people prefer to tell lies of omission about facts rather than lies of commission about feelings. 2. Don’t be afraid to exert direct influence on your counterpart’s emotions. This may sound manipulative or even unscrupulous, but you can use this influence for good. For example, if your counterpart seems anxious or angry, injecting humor or empathetic reassurance can dramatically change the tone of the interaction. By the same token, if your counterpart seems overconfident or pushy, expressing well-placed anger can inspire a healthy dose of fear. In recent research with Elizabeth Baily Wolf, I have found that it’s possible to go even further in managing others’ emotions: You display an emotion, your counterpart sees it, and then you shape his interpretation of it. For example, imagine that you start crying at work. (Crying is a difficult-to-control and often embarrassing behavior.) Saying “I’m in tears because I’m passionate” rather than “I’m sorry I’m so emotional” can completely change the way others react and the way they view your self-control and competence.Ch 15. Working Across Cultures (BY ANDY MOLINSKY) It’s harder to read others across borders.

Given the differences and the importance of getting it right when communicating across cultures, what are thoughtful managers to do? A first tip is to treat emotions like another language. If you’re traveling or moving to France, you’re bound to learn French, or at least some key phrases. Treat emotions in the same way. Try your best to learn the language of emotions in whatever culture you’re working in. Observe whether people tend to express emotions readily or keep them to themselves, and if, as in the Japan example above, there are differences in when and where people freely express emotion. Diagnose any gaps between how you’d express emotions in your culture and how people you’ll be interacting with express emotion in theirs. In addition to learning the language of emotions, make sure you also learn how to respond constructively when you do encounter emotions different from your own. For example, if you’re expecting a smile from your boss after suggesting a new idea but instead get a blank stare, don’t necessarily assume she hates you or your idea. Instead, gather more information to fully understand her point of view. You might ask a follow-up question to get a better sense of her opinion: Ask if your proposal was clear or if she felt your idea addressed the concerns she had. Keep in mind that cultural norms differ in terms of how appropriate it might be to ask questions like these to your boss, but the general idea is to do what you can to collect data to help you decipher emotional expressions, rather than relying solely on your initial, knee-jerk reaction or presumption.SECTION FIVE: Dealing with Difficult People Ch 16. Make Your Enemies Your Allies (BY BRIAN UZZI AND SHANNON DUNLAP) Reverse a rivalry by building trust.