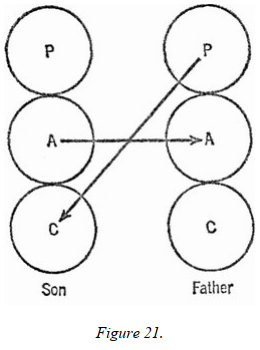

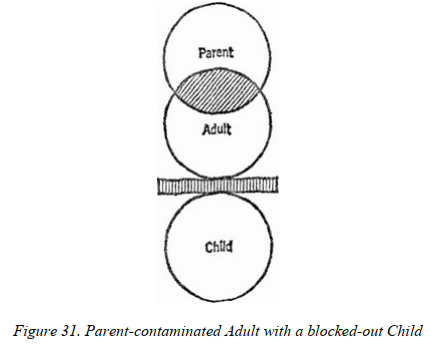

CHAPTER 1: Freud, Penfield, and Berne 1. The brain functions as a high-fidelity tape recorder. 2. The feelings which were associated with past experiences also are recorded and are inextricably locked to those experiences. 3. Persons can exist in two states at the same time. The patient knew he was on the operating table talking with Penfield; he equally knew he was seeing the 'Seven-Up Bottling Company... and Harrison Bakery'. He was dual in that he was at the same time in the experience and outside of it, observing it. 4. These recorded experiences and feelings associated with them are available for replay today in as vivid a form as when they happened and provide much of the data which determines the nature of today's transactions. These experiences not only can be recalled but also relived. I not only remember how I felt. I feel the same way now. ... The unit of social intercourse is called a transaction. If two or more people encounter each other... sooner or later one of them will speak, or give some other indication of acknowledging the presence of the others. This is called the transactional stimulus. Another person will then say or do something which is in some way related to the stimulus. and that is called the transactional response. CHAPTER 2: Parent, Adult, and Child The Parent The Parent is a huge collection of recordings in the brain of unquestioned or imposed external events perceived by a person in his early years, a period which we have designated roughly as the first five years of life. This is the period before the social birth of the individual, before he leaves home in response to the demands of society and enters school. (See Figure 2.) The name Parent is most descriptive of this data inasmuch as the most significant 'tapes' are those provided by the example and pronouncements of his own real parents or parent substitutes. Everything the child saw his parents do and everything he heard them say is recorded in the Parent. Everyone has a Parent in that everyone experienced external stimuli in the first five years of life. Parent is specific for every person, being the recording of that set of early experiences unique to him. ... Another characteristic of the Parent is the fidelity of the recordings of inconsistency. Parents say one thing and do another. Parents say, 'Don't lie,' but tell lies. They tell children that smoking is bad for their health but smoke themselves. They proclaim adherence to a religious ethic but do not live by it. It is not safe for the little child to question this inconsistency, and so he is confused. Because this data causes confusion and fear, he defends himself by turning off the recording. We think of the Parent predominantly as the recordings of the transactions between the child's two parents. It may be helpful to consider the recordings of Parent data as somewhat like the recording of stereophonic sound. There are two sound tracks that, if harmonious, produce a beautiful effect when played together. If they are not harmonious, the effect is unpleasant and the recording is put aside and played very little, if at all. This is what happens when the Parent contains discordant material. The Parent is repressed or, in the extreme, blocked out altogether. Mother may have been a 'good' mother and father may have been 'bad', or vice versa. There is much useful data which is stored as a result of the transmission of good material from one parent; but since the Parent does contain material from the other parent that is contradictory and productive of anxiety, the Parent as a whole is weakened or fragmented. Parent data that is discordant is not allowed to be a strong positive influence in the person's life. Another way to describe this phenomenon is to compare it with the algebraic equation: a plus times a minus equals a minus. It does not matter how big the plus was, or how little the minus was. The result is always a minus - a weakened, disintegrated Parent. The effect in later life may be ambivalence, discord, and despair - for the person, that is, who is not free to examine the Parent. ... Whether Parent data is a burden or a boon depends on how appropriate it is to the present, on whether or not it has been updated by the Adult, the function of which we shall discuss in this chapter. The Child While external events are being recorded as that body of data we call the Parent, there is another recording being made simultaneously. This is the recording of internal events, the responses of the little person to what he sees and hears. It is this 'seeing and hearing and feeling and understanding' body of data which we define as the Child. Since the little person has no vocabulary during the most critical of his early experiences, most of his reactions are feelings. We must keep in mind his situation in these early years. He is small, he is dependent, he is inept, he is clumsy, he has no words with which to construct meanings. Emerson said we 'must know how to estimate a sour look'. The child does not know how to do this. A sour look turned in his direction can only produce feelings that add to his reservoir of negative data about himself. It's my fault. Again. Always is. Ever will be. World without end. During this time of helplessness there are an infinite number of total and uncompromising demands on the child. On the one hand, he has the urges (genetic recordings) to empty his bowels ad lib., to explore, to know, to crush and to bang, to express feelings, and to experience all of the pleasant sensations associated with movement and discovery. On the other hand, there is the constant demand from the environment, essentially the parents, that he give up these basic satisfactions for the reward of parental approval. This approval, which can disappear as fast as it appears, is an unfathomable mystery to the child, who has not yet made any certain connexion between cause and effect. The predominant by-product of the frustrating, civilizing process is negative feelings. On the basis of these feelings the little person early concludes, I'm not OK.' We call this comprehensive self-estimate the not ok, or the not ok Child. This conclusion and the continual experiencing of the unhappy feelings which led to it and confirm it are recorded permanently in the brain and cannot be erased. This permanent recording is the residue of having been a child. Any child. Even the child of kind, loving, well-meaning parents. It is the situation of child-hood and not the intention of the parents which produces the problem. As in the case of the Parent, the Child is a state into which a person may be transferred at almost any time in his current transactions. There are many things that can happen to us today which recreate the situation of childhood and bring on the same feelings we felt then. Frequently we may find ourselves in situations where we are faced with impossible alternatives, where we find ourselves in a corner, either actually, or in the way we see it. These 'hook the Child', as we say, and cause a replay of the original feelings of frustration, rejection, or abandonment, and we relive a latter-day version of the small child's primary depression. Therefore, when a person is in the grip of feelings, we say his Child has taken over. When his anger dominates his reason, we say his Child is in command. The Adult At about ten months of age a remarkable thing begins to happen to the child. Until that time his life has consisted mainly of helpless or unthinking responses to the demands and stimulations by those around him. He has had a Parent and a Child. What he has not had is the ability either to choose his responses or to manipulate his surroundings. He has had no self-direction, no ability to move out to meet life. He has simply taken what has come his way. At ten months, however, he begins to experience the power of locomotion. He can manipulate objects and begins to move out, freeing himself from the prison of immobility. It is true that earlier, as at eight months, the infant may frequently cry and need help in getting out of some awkward position, but he is unable to get out of it by himself. At ten months he concentrates on inspection and exploitation of toys. The ten-month-old has found he is able to do something which grows from his own awareness and original thought. This self-actualization is the beginning of the Adult. Adult data accumulates as a result of the child's ability to find out for himself what is different about life from the 'taught concept' of life in his Parent and the 'felt concept' of life in his Child. The Adult develops a 'thought concept' of life based on data gathering and data processing. The motility which gives birth to the Adult becomes reassuring in later life when a person is in distress. He goes for a walk to 'clear his mind'. Pacing is seen similarly as a relief from anxiety. There is a recording that movement is good, that it has a separating quality, that it helps him see more clearly what his problem is. The Adult, during these early years, is fragile and tentative. It is easily 'knocked out' by commands from the Parent and fear in the Child. Mother says about the crystal goblet, 'No, no! Don't touch that!' The child may pull back and cry, but at the first opportunity he will touch it anyway to see what it is all about. In most persons the Adult, despite all the obstacles thrown in its way, survives and continues to function more and more effectively as the maturation process goes on. The Adult is 'principally concerned with transforming stimuli into pieces of information, and processing and filing that information on the basis of previous experience'. It is different from the Parent, which is 'judgemental in an imitative way and seeks to enforce sets of borrowed standards, and front the Child, which tends to react more abruptly on the basis of prelogical thinking and poorly differentiated or distorted perceptions'. Through the Adult the little person can begin to tell the difference between life as it was taught and demonstrated to him (Parent), life as he felt it or wished it or fantasized it (Child), and life as he figures it out by himself (Adult). The Adult is a data-processing computer, which grinds out decisions after computing the information from three sources: the Parent, the Child, and the data which the Adult has gathered and is gathering. One of the important functions of the Adult is to examine the data in the Parent, to see whether or not it is true and still applicable today, and then to accept it or reject it; and to examine the Child to see whether or not the feelings there are appropriate to the present or are archaic and in response to archaic Parent data. The goal is not to do away with the Parent and Child but to be free to examine these bodies of data. The Adult, in the words of Emerson, 'must not be hinderedby the name of goodness, but must examine if it be goodness'; or badness, for that matter, as in the early decision, 'I'm not ok'. The Adult testing of Parent data may begin at an early age. A secure youngster is one who finds that most Parent data is reliable: They told me the truth!' 'It really is true that cars in the street are dangerous,' concludes the little boy who has seen his pet dog hurt by a car in the street. 'It really is true that things go better when I share my toys with Bobby,' thinks the little boy who has been given a prized possession by Bobby. 'It really does feel better when my pants aren't wet,' concludes the little girl who has learned to go to the bathroom by herself. If parental directives are grounded in reality, the child, through his own Adult, will come to realize integrity, or sense of wholeness. What he tests holds up under testing. The data which he collects in his experimentation and examination begins to constitute some 'constants' that he can trust. His findings are supported by what he was taught in the first place. It is important to emphasize that the verification of Parent data does not erase the not ok recordings in the Child, which were produced by the early imposition of this data. Mother believes that the only way to keep three-year-old Johnny out of the street is to spank him. He does not understand the danger. His response is fear, anger, and frustration with no appreciation of the fact that his mother loves him and is protecting his life. The fear, anger, and frustration are recorded. These feelings are not erased by the later understanding that she was right to do what she did, but the understanding of how the original situation of childhood produced so many not ok recordings of this type can free us of their continual replay in the present. We cannot erase the recording, but we can choose to turn it off! Figure 5. The Adult gets data from three sources. In the same way that the Adult updates Parent data to determine what is valid and what is not, it updates Child data to determine which feelings may be expressed safely. In our society it is considered appropriate for a woman to cry at a wedding, but it is not considered appropriate for that woman to scream at her husband afterwards at the reception. Yet both crying and screaming are emotions in the Child. The Adult keeps emotional expression appropriate. (The evidence once told me space travel was only fantasy; now I know it is reality.) Another of the Adult's functions is probability estimating. This function is slow in developing in the small child and, apparently, for most of us, has a hard time catching up throughout life. The little person is constantly confronted with unpleasant alternatives (either you eat your spinach or you go without ice cream), offering little incentive for examining probabilities. Unexamined probabilities can underlie many of our transactional failures, and unexpected danger signals can cause more Adult 'decay', or delay, than expected ones. There are similarities here to the stock ticker in investment concerns, which may run many hours behind on very active trading days. We sometimes refer to this delay as 'computer lag', a remedy for which is the old, familiar practice of 'counting to ten'.The capacity for probability estimating can be increased by conscious effort. Like a muscle in the body, the Adult grows and increases in efficiency through training and use. If the Adult is alert to the possibility of trouble, through probability estimating, it can also devise solutions to meet the trouble if and when it comes. Under sufficient stress, however, the Adult can be impaired to the point where emotions take over inappropriately. The boundaries between Parent, Adult, and Child are fragile, sometimes indistinct, and vulnerable to those incoming signals which tend to recreate situations we experienced in the helpless, dependent days of childhood. The Adult sometimes is flooded by signals of the 'bad news' variety so overwhelming that the Adult is reduced to an 'onlooker' in the transaction. An individual in this situation might say, 'I knew what I was doing was wrong, but I couldn't help myself.' Unrealistic, irrational, non-Adult responses are seen in a condition referred to as traumatic neurosis. The danger, or 'bad news' signal, hits the Parent and the Child at the same time it hits the Adult. The Child responds in the way it originally did, with a feeling of not ok. This may produce all kinds of regressive phenomena. The individual may again feel himself to be a tiny, helpless, dependent child. One of the most primitive of these phenomena is thought blocking. One place this can be seen is in psychiatric hospitals that have a locked-door policy. When the door is locked on a new patient, his retreat is rapid and pronounced. This is why I am opposed to treating patients in a setting where the emphasis is on parental care. Catering to the helpless Child in the individual delays the reconstructive process of restoring the Adult to the executive function. An ideal hospital would be a comfortable motel with 'play area' for the Child, surrounding a clinic building devoted to activities designed for achieving autonomy of the Adult. The nurses would not wear uniforms or serve as parents to the Patients. Instead, nurses in street clothing would apply their skills and training to help each individual learn the identity of his Parent, Adult, and Child. In our treatment groups we use certain colloquial catch phrases such as, 'Why don't you stay in your Adult?' when a member finds his feelings are taking over. Another of these is, 'What was the original transaction?' This is asked as means of 'turning on the Adult' to analyse the similarity between the present incoming signal producing the present distress and the original transaction, in which the small child experienced distress. The ongoing work of the Adult consists, then, of checking out old data, validating or invalidating it, and refiling it for future use. If this business goes on smoothly and there is a relative absence of conflict between what has been taught and what is real, the computer is free for important new business, creativity. Creativity is born from curiosity in the Child, as is the Adult. The Child provides the 'want to' and the Adult provides the 'how to'. The essential requirement for creativity is computer time. If the computer is cluttered with old business there is little time for new business. Once checked out, many Parent directives become automatic and thus free the computer for creativity. Many of our decisions in day-to-day transactions are automatic. For instance, when we see an arrow pointing down a one-way street, we automatically refrain from going the oppositeway. We do not involve our computer in lengthy data processing about highway engineering, the traffic death toll, or how signs are painted. Were we to start from scratch in every decision or operate entirely without the data that was supplied by our parents, our computer would rarely have time for the creative process. Some people contend that the undisciplined child, unhampered by limits, is more creative than the child whose parents set limits. I do not believe this is true. A youngster has more time to be creative - to explore, invent, take apart, and put together - if he is not wasting time in futile decision making for which he has inadequate data. A little boy has more time to build a snowman if he is not allowed to engage Mother in a long hassle about whether or not to wear overshoes. If a child is allowed to be creative by painting the front room walls with shoe polish, he is unprepared for the painful consequences when he does so at the neighbour's house. Painful outcomes do not produce ok feelings. There are other consequences that take time, such as mending in the hospital after a trial-and-error encounter with a car in the street. There is just so much computer time. Conflict uses a great deal. An extremely time-consuming conflict is produced when what parents say is true does not seem to be true to the Adult. The most creative individual is the one who discovers that a large part of the content of the Parent squares with reality. He can then file away this validated information in the Adult, trust it, forget about it, and gets on with other things - like how to make a kite fly, how to build a sand castle, or how to do differential calculus. However, many youngsters are preoccupied much of the time with the conflict between Parent data and what they see as reality. Their most troubling problem is that they do not understand why the Parent has such a hold on them. When Truth comes to knock at the Parent's door, the Parent says, 'Come, let us reason together'. The little child whose father is in jail and whose mother steals to support him may have a loud recording in his Parent, 'You never trust a cop!' So he meets a friendly one. His Adult computes all the data about this nice guy, how he gets the ball game started in the sand lot, how he treats the gang to popcorn, how he is friendly, and how he speaks in a quiet voice. For this youngster there is conflict. What he sees as reality is different from what he has been taught. The Parent tells him one thing and the Adult another. During the period of his actual dependency upon his parents for security, however tenuous this security may be, it is likely he will accept the parents' verdict that cops are bad. This is how prejudice is transmitted. For a little- child, it may be safer to believe a lie than to believe his own eyes and ears. The Parent so threatens the Child (in a continuing internal dialogue) that the Adult gives up and stops trying to inquire into areas of conflict. Therefore, 'cops are bad' comes through as truth. This is called contamination of the Adult and will be examined in Chapter 6. CHAPTER 3: The Four Life Positions Very early in life every child concludes, 'I'm not OK.' He makes a conclusion about his parents, also: 'You're OK'. This is the first thing he figures out in his life-long attempt to make sense of himself and the world in which he lives. This position, I'm not ok - you're ok, is the most deterministic decision of his life. It is permanently recorded and will influence everything he does. Because it is a decision it can be changed by a new decision. But not until it is understood. Transactional Analysis constructs the following classification of the four possible life positions held with respect to oneself and others: 1. I'm Not Ok - You're Ok 2. I'm Not Ok - You're Not Ok 3. I'm Ok - You're Not Ok 4. I'm Ok - You're Ok Before I elaborate each position I wish to state a few general observations about positions. I believe that by the end of the second year of life, or sometime during the third year, the child has decided on one of the first three positions. The I'm not ok - you're ok is the first tentative decision based on the experiences of the first year of life. By the end of the second year it is either confirmed and settled or it gives way to Position 2 or 3: I'm not ok-you're not ok or I'm ok-you're not ok. Once finalized, the child stays in his chosen position and it governs everything he does. It stays with him the rest of his life, unless he later consciously changes it to the fourth position. People do not shift back and forth. The decision as to the first three positions is based totally on stroking and non-stroking. The first three are nonverbal decisions. They are conclusions, not explanations. Yet they are more than conditioned responses. They are what Piaget calls intellectual elaborations in the construction of causality. In other words, they are a product of Adult data processing in the very little person. 1. I'm Not OK-You're OK This is the universal position of early childhood, being the infant's logical conclusion from the situation of birth and infancy. There is OK-ness in this position, because stroking is present. Every child is stroked in the first year of life simply by the fact that he has to be picked up to be cared for. Without at least minimal handling the infant would not survive. There is also NOT-OK-ness. That is the conclusion about himself. I believe the evidence points to the overwhelming accumulation of not ok feelings in the child, making logical (on the basis of the evidence he- has) his not ok conclusion about himself. In explaining Transactional Analysis to patients and nonpatients I have found a generally that's it! response to the explanation of the origin and existence of the not ok Child. I believe that acknowledging the not ok Child in each of us is the only sympathetic, thus curative, way games can be analysed. Considering the universality of games, the universality of the I'm not ok is a reasonable deduction. Adler's break with Freud was over this point: sex was not at the basis of man's struggle in life, but rather feelings of inferiority, or not ok, which were apparent universally. He claimed that the child, by virtue of his small size and helplessness, inevitably considered himself inferior to the adult figures in his environment. Harry Stack Sullivan was greatly influenced by Adler, and I was greatly influenced by Sullivan, with whom I studied for the five years preceding his death. Sullivan, whose central contribution to psychoanalytic thought was the concept of 'interpersonal relationships', or transactions, claimed that the child built hisself-estimate totally on the appraisal of others, what he called 'reflected appraisals'. He said: The child lacks the equipment and experience necessary to form an accurate picture of himself, so his only guide is the reactions of others to him. There is very little cause for him to question these appraisals, and in any case he is far too helpless to challenge them or to rebel against them. He passively accepts the judgements, which are communicated empathetically at first, and by words, gestures, and deeds in this period... thus the selfattitudes learned early in life are carried forever by the individual, with some allowance for the influence of extraordinary environmental circumstances and modification through later experiences. 2. I'm NOT OK - You're Not OK If all children who survive infancy initially conclude I'm not ok-you're ok, what happens to produce the second position, I'm not ok and neither are you? What happened to the you're ok? What happened to the source of stroking? By the end of the first year something significant has happened to the child. He is walking. He no longer has to be picked up. If his mother is cold and nonstroking, if she only put up with him during the first year because she had to, then his learning to walk means that his 'babying' days are over. The stroking ceases entirely. In addition punishments come harder and more often as he is able to climb out of his crib, as he gets into everything, and won't stay put. Even self-inflicted hurts come more frequently as his mobility sends him tripping over. obstacles and tumbling down stairs. Life, which in the first year had some comforts, now has none. The stroking has disappeared. If this state of abandonment and difficulty continues without relief through the second year of life, the child concludes I'm not ok - you're not ok. In this position the Adult stops developing since one of its primary functions - getting strokes - is thwarted in that there is no source of stroking. A person in this position gives up. There is no hope. He simply gets through life and ultimately may end up in a mental institution in a state of extreme withdrawal, with regressive behaviour which reflects a vague, archaic longing to get back to life as it was in the first year during which he received the only stroking he ever knew - as an infant who was held and fed. 3. I'm OK - You're Not OK A child who is brutalized long enough by the parents he initially felt were ok will switch positions to the third, or criminal, position: I'm ok - you're not ok. There is OK-ness here, but where does it come from? Where is the source of stroking if you're not ok? This is a difficult question considering that the position is decided in the second or third year of life. If a two-year-old concludes I'm ok, does this mean his ok is the product of 'self-stroking', and, if so, how does a small child stroke himself? I believe this self-stroking does in fact occur during the time that a little person is healing from major, painful injuries such as are inflicted on a youngster who has come to be known as 'the battered child'. This is the child who has been beaten so severely that bones and skin are broken. Anyone who has had a broken bone or massive bruises knows the pain. Common in battered children are extremely painful injuries such as broken ribs, smashed kidneys, and fractured skulls. How does the every-breath agony of broken ribs or the excruciating headache from blood in the spinal fluid feel to a toddler? Every hour five infants in this country receive injuries of this kind at the hands of their parents. I believe that it is while this little individual is healing, in a sense 'lying there licking his wounds', that he experiences a sense of comfort alone and by himself, if for no other reason than that his improvement is in such contrast to the gross pain he has just experienced. It is as if he senses, I'll be all right if you leave me alone. I'm ok by myself. As the brutal parents reappear, he may shrink in horror that it will happen again. You hurt me! You are not ok. I'm ok - you're not ok. The early history of many criminal psychopaths, who occupy this position, reveal this kind of gross physical abuse. The person in the I'm ok - you're not ok position suffers from stroking deprivation. A stroke is only as good as the stroker. And there are no ok people. Therefore there are no ok strokes. Such a person may develop a retinue of 'yes men' who praise and stroke him heavily. Yet he knows they are not authentic strokes because he has had to set them up himself, in the same way he had to produce his own stroking in the first place. The more they praise him the more despicable they become, until he finally rejects them all in favour of a new group of yes men. 'Come close so I can let you have it' is an old recording. That's the way it was in the beginning. 4. I'm OK - You're Ok There is a fourth position, wherein lies our hope. It is the I'm ok - you're ok position. There is a qualitative difference between the first three positions and the fourth position. The first three are unconscious, having been made early in life. I'm not ok - you're ok came first and persists for most people throughout life. For certain extremely unfortunate children this position was changed to positions two and three. By the third year of life one of these positions is fixed in every person. The decision as to position is perhaps one of the first functions of the infant's Adult in the attempt to make sense out of life, so that a measure of predictability may be applied to the confusion of stimuli and feelings. These positions are arrived at on the basis of data from the Parent and Child. They are based on emotion or impressions without the benefit of external, modifying data. The fourth position, I'm ok-you're ok, because it is a conscious and verbal decision, can include not only an infinitely greater amount of information about the individual and others, but also the incorporation of not-yet-experienced possibilities which exist in the abstractions of philosophy and religion. The first three positions are based on feelings. The fourth is based on thought, faith, and the wager of action. The first three have to do with why. The fourth has to do with why not} Our understanding of ok is not bound to our own personal experiences, because we can transcend them into an abstraction of ultimate purpose for all men. We do not drift into a new position. It is a decision we make. In this respect it is like a conversion experience. We cannot decide on the fourth position without a great deal more information than most persons have available to them about the circumstances surrounding the original positions decided on so early in life. Fortunate are the children who are helped early in life to find they are ok by repeated exposure to situations in which they can prove, to themselves, their own worth and the worth of others. Unfortunately, the most common position, shared by 'successful' and 'unsuccessful' persons alike, is the I'm not ok - you're ok position. Finally, it is essential to understand that I'm ok-you're ok is a position and not a feeling. The not ok recordings in the Child are not erased by a decision in the present. The task at hand is how to start a collection of recordings which play ok outcomes to transactions, successes in terms of correct probability estimating, successes in terms of integrated actions which make sense, which are programmed by the Adult, and not by the Parent or Child, successes based on an ethic which can be supported rationally. A man who has lived for many years by the decisions of an emancipated Adult has a great collection of such past experiences and can say with assurance, 'I know this works'. The reason "I'm ok - you're ok" works is that instant joy or tranquility is not expected. Personal or social storms are not going to subside immediately when we assume a new position. The Child wants immediate results - like instant coffee, and immediate relief from acid indigestion. The Adult can comprehend that patience and faith are required. We cannot guarantee instant ok feelings by the assuming of the I'm-ok-you're-ok position. We have to be sensitive to the presence of the old recordings; but we can choose to turn them off when they replay in a way that undermines the faith we have in a new way to live, which, in time, will bring forth new results and new happiness in our living. The Adult also can recognize the Child responses in others and can choose not to respond in kind. CHAPTER 4: We Can Change All men plume themselves on the improvement of society, and no man improves. - Ralph Waldo Emerson The Emancipated Adult The goal of Transactional Analysis is to enable a person to have freedom of choice, the freedom to change at will, to change the responses to recurring and new stimuli. Much of this freedom is lost in early childhood, marking the onset, according to Kubie, of the 'neurotic process'. This process is one which is continually involved in solving archaic problems to the exclusion of dealing effectively with today's reality. Restoration of the freedom to change is the goal of treatment. This freedom grows from knowing the truth about what is in the Parent and what is in the Child and how this data feeds into present-day transactions. It also requires the truth, or the evidence, about the world in which he lives. Such freedom requires the knowledge that everyone with whom one deals has a Parent, an Adult, and a Child. It requires persistent exploration not only into 'knowable' areas but also into indeterminate areas, which can best be understood in terms of another function of the Adult, that of probability estimating. One of the realities of the human predicament is that we frequently have to make decisions before all the facts are in. This is true of any commitment. It is true of marriage. It is true of voting. It is true of signing a petition. It is true of the establishment of priorities. It is true of those values we embrace independently - that is, with the Adult. The Child in us demands certainty. The Child wants to know the sun will come up every morning, that Mother will be there, that the 'bad guy' will always get it in the end; but the Adult can accept the fact that there is not always certainty. Philosopher Elton Trueblood states: The fact that we do not have absolute certainty in regard to any human conclusions does not mean that the task of inquiry is fruitless. We must, it is true, always proceed on the basis of probability, but to have probability is to have something. What we seek in any realm of human thought is not absolute certainty, for that is denied us as men, but rather the more modest path of those who find dependable ways of discerning different degrees of probability. --- A note on contamination and prejudice: CHAPTER 5: Analysing the Transaction Now that we have developed a language, we come to the central technique: using that language to analyse a transaction. The transaction consists of a stimulus by one person and a response by another, which response in turn becomes a new stimulus for the other person to respond to. The purpose of the analysis is to discover which part of each person - Parent, Adult, or Child - is originating each stimulus and response. There are many clues to help identify stimulus and response as Parent, Adult, or Child. These include not only the words used but also the tone of voice, body gestures, and facial expressions. The more skilful we become in picking up these clues, the more data we acquire in Transactional Analysis. We do not have to dig deep into anecdotal material in the past to discover what is recorded in Parent, Adult, and Child. We reveal these aspects in ourselves every day. The following is a list of physical and verbal clues for each state. Parent Clues - Physical: Furrowed brow, pursed lips, the pointing index finger, headwagging, the 'horrified look', foot-tapping, hands on hips, arms folded across chest, wringing hands, tongue-clicking, sighing, patting another on the head. These are typical Parent gestures. However, there may be other Parent gestures peculiar to one's own Parent. For instance, if your father had a habit of clearing his throat and looking skyward each time he was to make a pronouncement about your bad behaviour, this mannerism undoubtedly would be apparent as your own prelude to a Parent statement, even though this might not be generally seen as Parent in most people. Also, there are cultural differences. For instance, in the United States people exhale as they sigh, whereas in Sweden they inhale as they sigh. Parent Clues - Verbal: I am going to put a stop to this once and for all; I can't for the life of me...; Now always remember... ('always' and 'never' are almost always Parent words, which reveal underlying limitations of an archaic system closed to new data); How many times have I told you? If I were you... Many evaluative words, whether critical or supportive, may identify the Parent inasmuch as they make a judgement about another, based not on Adult evaluation but on automatic, archaic responses. Examples of these kinds of words are: stupid, naughty, ridiculous, disgusting, shocking, asinine, lazy, nonsense, absurd, poor thing, poor dear, no! no!, sonny, honey (as from a solicitous saleslady), How dare you?, cute, there there, Now what?, Not again! It is important to keep in mind that these words are clues, and are not conclusive. The Adult may decide after serious deliberation that, on the basis of an Adult ethical system, certain things are stupid, ridiculous, disgusting, and shocking. Two words, 'should' and 'ought', frequently are giveaways to the Parent state, but as I contend in Chapter 12, 'should' and 'ought' can also be Adult words. It is the automatic, archaic, unthinking use of these words which signals the activation of the Parent. The use of these words, together with body gestures and the context of the transaction, help us identify the Parent. Child Clues - Physical: Since the Child's earliest responses to the external world were nonverbal, the most readily apparent Child clues are seen in physical expressions. Any of the following signal the involvement of the Child in a transaction: tears; the quivering lip; pouting; temper tantrums; the high-pitched, whining voice; rolling eyes; shrugging shoulders; downcast eyes; teasing; delight; laughter; hand-raising for permission to speak; nail-biting; nose-thumbing; squirming; and giggling. Child Clues - Verbal: Many words, in addition to baby talk, identify the Child: I wish, I want, I dunno, I gonna, I don't care, I guess, when I grow up, bigger, biggest, better, best (many superlatives originate in the Child as 'playing pieces' in the 'Mine Is Better' game). In the same spirit as 'Look, Ma, no hands', they are stated to impress the Parent and to overcome the not ok. There is another grouping of words which are spoken continually by little children. However, these words are not clues to the Child, but rather to the Adult operating in the little person. These words are why, what, where, who, when, and how. Adult Clues - Physical: What does the Adult look like? If we turn off the video on the Parent and Child tapes, what will come through on the face? Will it be blank? Benign? Dull? Insipid? Ernst {1} contends that the blank face does not mean an Adult face. He observes that listening with the Adult is identified by continual movement - of the face, the eyes, the body-with an eye blink every three to five seconds. Non-movement signifies non-listening. The Adult face is straight-forward, says Ernst. If the head is tilted, the person is listening with an angle in mind. The Adult also allows the curious, excited Child to show its face. Adult Clues - Verbal: As stated before, the basic vocabulary of the Adult consists of why, what, where, when, who, and how. Other words are: how much, in what way, comparative, true, false, probable, possible, unknown, objective, I think, I see, it is my opinion, etc. These words all indicate Adult data processing. In the phrase 'it is my opinion', the opinion may be derived from the Parent, but the statement is Adult in that it is identified as an opinion and not as fact. 'It is my opinion that high school students should have the vote' is not the same as the statement 'High school students should have the vote'. This chapter then goes onto telling about the various possible ways a transaction might go on: 1. Parent-Parent transaction 2. Adult-adult transaction 3. Child-child transaction 4. Child-parent transation (Such as between sick husband (little boy) and nurturing wife (good mamma)). 5. Parent-child transaction 6. Child-adult transaction 7. Adult-parent transaction Uncomplementary, or Crossed, Transactions Additional Illustrations of Crossed Transactions Patient (A): I would like to work in a hospital like this. Nurse (P): You can't cope with your own problems. (Figure 18) Mother (P): Go clear up your room. Daughter (P): You can't tell me what to do. You're not the boss around here. Dad's the boss! (Figure 19) Therapist (A): What is your principal hang-up in life? Patient (C): Red tape, red tape (pounding table), damn it, red tape! (Figure 20) Son (A): I have to finish a report tonight that's due tomorrow. Father (P): Why do you always leave things to the last minute? (Figure 21) Man (A), standing with friend: We were trying to get this cap unlocked and dropped the key behind the bumper. Could you help us get it out? Service Station Attendant (P): Who did it? (Figure 22) Little Girl (A): Dirty shirts are warm. Mother (P): Go take a bath. (Figure 23) Adolescent Girl (P): Well, frankly, my Father likes Palm Springs best. Friend (P): Our family tries to avoid the tourist places. (Figure 24) Little Girl (C): I hate soup. I'm not going to eat it. You cook icky. Mother (C): I'm just going to leave and then you can cook your own icky food. (Figure 25) Little Boy (C): My Daddy has a million dollars. Little Girl (C): That's nothing. My Daddy has 'finnegan' dollars. ('Finnegan' was this fouryear-old's way of saying 'infinity'.) (Figure 26) Duplex Transactions Husband says to wife, 'Where did you hide the can opener?' The main stimulus is Adult in that it seeks objective information. But there is a secondary communication in the word hide. (Your house-keeping is a mystery to me. We'd go broke if I were as disorganized as you. If I could once, just once, find something where it belongs!) This is Parent. It is a thinly veiled criticism. This stimulates a duplex transaction (Figure 28). The progress of this transaction depends on which stimulus the wife wishes to respond to. If she wants to keep things amiable and feels ok enough not to have been threatened she may respond, 'I hid it next to the tablespoons, darling'. This is complementary in that she gives him the information he desires and also acknowledges good-naturedly his 'aside' about her housekeeping. If her Adult computes that it is important to her marriage to do something about her husband's gentle suggestion, she may take the hint and become more organized. With her Adult handling the transaction, she can. However, if her not ok Child is hooked, her primary response will be to the word hide, and she may respond along the lines of, 'So what's the matter with you - you blind or something?' And there endeth the quest for the can opener while they wrangle over each other's merits and demerits in the area of organization, blindness, stupidity, etc. His beer is still unopened, and a game of 'Uproar' is well along. Some transactions of this nature can involve stimulus and response at all levels: A man comes home and writes 'I love you' in the dust on the coffee table. The Adult is in command of the situation, although both his Parent and Child are involved (Figure 29). The Parent says, 'Why don't you ever clean this place up?' The Child says, 'Please don't get mad at me if I criticize you'. The Adult takes charge, however, on the basis that to be loving is important to my marriage, so I won't let my Parent or my Child be activated. If I tell her I love her she won't get mad at me, but perhaps she'll get the idea that it is important, after all, for a man in my position to have a home that looks nice. This can turn into a complementary transaction if the wife is ok enough to take a little constructive criticism. The outcome would be happy if she shined up the house, met her husband at the door with a tall, cool drink, and told him what a sweet, sentimental, imaginative husband he is: Other husbands just moan and groan - but look what a jewel I've got! This approach is bound to succeed. However, if she can't do this, her Parent will probably retort, 'When was the last time you cleaned the garage' or her Child will send her out on the town to run up the charge accounts. This transaction illustrates that even though the Parent and Child are involved, the outcome can be amiable and advance a good marriage if the Adult is in charge. The Adult has a choice as to how it will respond to a stimulus in a complementary way that will protect both the relationship and the individuals in the relationship. This sometimes takes some very rapid (intuitive) computing. The person who always comes out 'smelling like a rose' does not do so accidentally. He has a high-speed Adult. As handy as this is in social situations, as above, it is not as critical there as in the home. You can walk away from a cocktail party. Walking away from home is something else. The question arises: How can the Adult work better and faster? When someone knocks on the front door of life, who is going to get there first - the Parent, the Adult, or the Child? How to Stay in the Adult In summary, a strong Adult is built in the following ways: 1. Learn to recognize your Child, its vulnerabilities, its fears, its principal methods of expressing these feelings. 2. Learn to recognize your Parent, its admonitions, injunctions, fixed positions, and principal ways of expressing these admonitions, injunctions, and positions. 3. Be sensitive to the Child in others, talk to that Child, stroke that Child, protect that Child, and appreciate its need for creative expression as well as the not ok burden it carries about. 4. Count to ten, if necessary, in order to give the Adult time to process the data coming into the computer, to sort out Parent and Child from reality. 5. When in doubt, leave it out. You can't be attacked for what you didn't say. 6. Work out a system of values. You can't make decisions without an ethical framework. How the Adult works out a value system is examined in detail in Chapter 12, 'P-A-C and Moral Values'. CHAPTER 6: How We Differ All people are structurally alike in that they all have a Parent, an Adult, and a Child. They differ in two ways: in the content of Parent, Adult, and Child, which is unique to each person, being recordings of those experiences unique to each; and in the working arrangement, or the functioning, of Parent, Adult, and Child.This chapter is devoted to an examination of these functional differences. There are two kinds of functional problems: contamination and exclusion. Contamination At the end of an initial hour in which I had explained P-A-C to a sixteen-year-old girl who was withdrawn, uncommunicative, culturally deprived, a school dropout, and referred by the Welfare Department, I asked, 'Can you tell me what P-A-C means to you now?' After a long silence she said, 'It means that we are all made up of three parts and we'd better keep them separated or we're in trouble'. The trouble when they are not separated is called contamination of the Adult. Ideally (Figure 30) the P-A-C circles are separate. In many people, however, the circles overlap. The (a) overlap in the figure is contamination of the Adult by dated, unexamined Parent data which is externalized as true. This is called prejudice. Thus, beliefs such as 'white skins are better than black skins', 'right-handedness is better than left-handedness', and 'cops are bad' are externalized in transactions on the basis of prejudgement, before reality data (Adult) is applied to them. Prejudice develops in early childhood when the door of inquiry is shut on certain subjects by the security-giving parents. The little person dares not open it for fear of parental rebuke. We all know how difficult it is to reason with a prejudiced person. With some people one can present a logical and evidential case regarding racial issues or left-handedness or any other subject that the person holds a prejudice about; yet, the Parent in these people steadfastly dominates a portion of the Adult, and they will surround their prejudicial cases with all kinds of irrelevant arguments to support their position. As illogical as their position may seem, the rigidity of their position is in its safety. As illustrated in Chapter 2, it is safer for a little child to believe a lie than to believe his own eyes and ears. Therefore, one cannot eliminate prejudice by an Adult discourse on the subject of the prejudice. The only ways to eliminate prejudice are to uncover the fact that it is no longer dangerous to disagree with one's parents and to update the Parent with data from today's reality. Thus, treatment can be seen as separating Parent and Adult and restoring the boundary between them. The (b) overlap in Figure 30 is contamination of the Adult by the Child in the form of feelings or archaic experiences which are inappropriately externalized in the present. Two of the most common symptoms of this kind of contamination are delusions and hallucinations. A delusion is grounded in fear. A patient who said to me, 'The world is hideous', was describing how the world seemed to him as a small child. A little person who was in constant fear of brutality at the hands of angry, unpredictable parents can, as a grownup, under stress, be flooded by the same fear to the extent that he can fabricate 'logical' supporting data. He may believe that the door-to-door salesman coming down the street is really coming to kill him. If confronted with the fact that it is only a salesman, this person may support his fear by a statement such as 'I knew it the minute I saw him. It's him! He's wanted by the FBI. I saw his picture in the post office. That's why he's coming to get me'. As in the case of prejudice, this delusion cannot be eliminated by a simple statement of the truth that this is, in fact, a salesman. It can only be eliminated by uncovering the truth that the original threat to the Child no longer exists externally. Only as the Adult is decontaminated is it able to compute reality data. Hallucinations are another type of contamination of the Adult by the Child. An hallucination is a phenomenon produced by extreme stress, wherein what was once experienced externally - derogation, rejection, criticism - is again experienced externally, even though 'no one is there'. A recorded experience 'comes on for real' and the person 'hears' voices that existed in a past reality. If you ask him what the voices say, he characteristically will describe the content as words of criticism, threat, or violence. The more bizarre the hallucination the more bizarre was life for him as a child. Bizarre hallucinations are not hard to understand when we consider the actual types of abuse, verbal and physical, to which some children are subjected. Exclusion In addition to contamination there is another functional disorder that explains how we differ: exclusion. Exclusion is manifested by a stereotyped, predictable attitude which is steadfastly maintained as long as possible in the face of any threatening situation. The constant Parent, the constant Adult, and the constant Child all result primarily from defensive exclusion of the two complementary aspects in each case. {2} This is a situation in which an Excluding Parent can 'block out' the Child or an Excluding Child can 'block out' the Parent. The Person Who Cannot Play The Person Without a Conscience The Decommissioned Adult CHAPTER 7: How We Use Time One of the most dramatic scientific adventures of this century is the exploration of space. We are not content to understand that it is infinite. We want landmarks, so to speak, platforms for our satellites, or mathematical slots into which we can aim our space vehicles. We want to comprehend space; to define it; in a sense, to use it. The other great cosmic reality is time. We may speculate about either end of our earthly existence. We may trust in immortality in the face of incomprehensible death; but, as in our efforts to define space, we must in our definition of time start where we are. All we can know is that man's average ration of time is three score and ten years. What we do with our known allotment is what concerns us. Of most immediate concern is what we do with the smaller blocks of time within our grasp: the next week, the next day, the next hour, this very hour. We all share with Disraeli a common concern that 'life is too short to be little'. Yet our greatest frustration is that so much of life is just that. Perhaps more significant and dramatic than space exploration is an investigation of our use of time. 'What folly,' said John Howe, 'to dread the thought of throwing away life at once, and yet have no regard to throwing it away by parcels and piecemeal.' As with space, we are not content to comprehend time only as infinite. For many people the pressing question is 'How am I going to get through the next hour?' The more structured time is, the less difficult is this problem. Very busy people with many external demands do not have time on their hands. The 'next hour' is very well programmed. This programming, or structuring, is what people try to achieve, and when they are unable to do it themselves, they look to others to structure time for them. 'Tell me what to do.' 'What shall I do next?' 'What we need is leadership.' Structure hunger is an outgrowth of recognition hunger, which grew from the initial stroking hunger. The small child has not the necessary comprehension of time to structure it but simply sets about doing things which feel good, moment to moment. As he gets a little older he learns to postpone gratifications for greater rewards: 'I can go outside and make mudpies with Susie now, but if I wait twenty more minutes and keep my nice dress on, I can go to the shopping centre with Daddy.' This is basically a problem in structuring time. Which alternative will be more fun? Which will bring a greater reward? As we grow older we have more and more choices. However, the not ok position keeps us from exercising these choices as freely as we might think we do. In our observation of transactions between people, we have been able to establish six types of experience, which are inclusive of all transactions. They are withdrawal, rituals, activities, pastimes, games, and intimacy. Withdrawal, although it is not a transaction with another person, can take place, nonetheless, in a social setting. A man, having lunch with a group of boring associates more concerned about their own stroking than his, may withdraw into the fantasy of the night before, when the stroking was good. His body is still at the lunch table, but 'he' isn't. Schoolrooms on a nice spring day are filled with bodies whose 'occupants' are down at the swimming hole, shooting into space on a blazing rocket, or recalling how nice it was kissing under the wisteria. Whenever people withdraw in such fashion it is always certain that the withdrawal keeps them apart from those they are with bodily. This is fairly harmless unless it happens all the time, or unless your wife is talking to you. A ritual is a socially programmed use of time where everybody agrees to do the same thing. It is safe, there is no commitment to or involvement with another person, the outcome is predictable, and it can be pleasant in so far as you are 'in step' or doing the right thing. There are worship rituals, greeting rituals, cocktail party rituals, bedroom rituals. The ritual is designed to get a group of people through the hour without having to get close to anyone. They may, but they don't have to. It is more comfortable to go to a High Church Mass than to attend a revival service where one may be asked, 'Are you saved, brother?' Sexual relations are less awkward in the dark for people for whom physical intimacy has no involvement at the level of personality. There is less chance for involvement in throwing a cocktail party than in having a dinner for six. There is little commitment, therefore little fulfilment. Rituals, like withdrawal, can keep us apart. An activity, according to Berne, is a 'common, convenient, comfortable and utilitarian method of structuring time by a project designed to deal with the material of external reality'. {1} Common activities are keeping business appointments, doing the dishes, building a house, writing a book, shovelling snow, and studying for exams. These activities, in that they are productive or creative, may be highly satisfying in and of themselves, or they may lead to satisfactions in the future in the nature of stroking for a job well done. But during the time of the activity, there is no need for intimate involvement with another person. There may be, but there does not have to be. Some people use their work to avoid intimacy, working nights at the office instead of coming home, devoting their lives to making a million instead of making friends. Activities, like withdrawal and rituals, can keep us apart. Pastimes are a way of passing time. Berne defines a pastime as ... an engagement in which the transactions are straightforward ... With happy or well organized people whose capacity for enjoyment is unimpaired, a social pastime may be indulged in for its own sake and bring its own satisfactions. With others, particularly neurotics, it is just what the name implies, a way of passing (i.e., structuring) the time: until one gets to know people better, until this hour has been sweated out, and on a larger scale, until bed-time, until vacation time, until school starts, until the cure is forthcoming, until some form of charism, rescue, or death arrives. Existentially a pastime is a way of warding off guilt, despair, or intimacy, a device provided by nature or culture to ease the quiet desperation. More optimistically, at best it is something enjoyed for its own sake and at least it serves as a means of getting acquainted in the hope of achieving the longed-for crasis with another human being. In any case, each participant uses it in an opportunistic way to get whatever primary and secondary gains he can from it. People who cannot engage in pastimes at will are not socially facile. Pastimes can be thought of as being a type of social probing where one seeks information about new acquaintances in an unthreatening, noncommittal way. Berne's observation is that 'pastimes form the basis for the selection of acquaintances and may lead to friendship' and further that they have as an advantage the 'confirmation of role and the stabilizing of position'. Berne has given some delightful and disarming names to certain of these pastimes, which can be recognized at cocktail parties, women's luncheons, family reunions, and the Kiwanis Club as: variations of 'Small Talk', such as 'General Motors' (comparing cars) and "Who Won' (both 'man talk'); 'Grocery', 'Kitchen', and 'Wardrobe' (all 'lady talk'); 'How To' (go about doing something); 'How Much' (does it cost?); 'Ever Been' (to some nostalgic place); 'Do You Know' (So-and-So); 'What Became Of (Good Old Joe); 'Morning After' (what a hang-over!); and 'Martini' (I know a better way). {3} Pastimes may be played by the Parent, Adult, or Child. A parent-Parent pastime was initiated by the following transaction: Maude: You mean you do upholstery? Bess: Only when necessary. This led to a discussion of the high price of having it done, how shoddy work is these days, and the sale at Macy's. One Child-Child pastime is the sharing of impossible alternatives symbolic of the damned-if-you-do and damned-if-you-don't situation of the little child. Anxiety may be relieved by this pastime, not because the problem is solved, but because it is handed to someone else - 'Here, you struggle with this for a while!' The following questions were overheard in an exchange between two five-year-olds: Would you rather eat a hill full of ants or drink a pail of boiling medicine? Would you rather be chased by a wild bull or wear your shoes on the wrong feet all day? Would you rather sit on a hot stove or go through the washing machine fifty times? Would you rather be stung by a thousand wasps or sleep in the pigpen? Answer one or the other! You have to answer one or the other. Grown-up versions may be more sophisticated, as, Are you a Democrat or a Republican? The Adult may play pastimes about such subjects as the weather in order to keep a relationship going until something interesting or stroke-producing appears: Mr A: Looks like a storm coming up. Mr B: Those clouds really look black. Mr A: Reminds me of the time I was flying my plane and ran into a squall over San Francisco Bay. Mr B: Oh, you fly? As useful as pastimes may be in certain social situations, it is evident that relationships that do not progress beyond them die or, at best, exist in quiet desperation and growing boredom. Pastimes, like withdrawal, rituals, and activities, can keep people apart. Games are such significant transactional phenomena that Berne has devoted a whole book to them, his best-selling Games People Play. Most games cause trouble. They are the relationship wreckers and the misery producers, and in understanding them lies the answer to 'why does this always happen to me?' The word 'game' should not be misleading, explains Berne. It does not necessarily imply fun or even enjoyment. For a full understanding of games, his book is recommended. However, the following is a brief definition, which will serve the purposes of this guide to Transactional Analysis. A game is an ongoing series of complementary ulterior transactions progressing to a well-defined,, predictable outcome, Descriptively it is a recurring set of transactions, often repetitious, superficially plausible, with a concealed motivation; or, more colloquially, a series of moves with a snare, or 'gimmick'. Games are clearly differentiated from procedures, rituals, and pastimes by two chief characteristics: (1) their ulterior quality and (2) the payoff, Procedures may be successful, rituals effective, and pastimes profitable, but all of them are by definition candid; they may involve contest, but not conflict and the ending may be sensational, but it is not dramatic. Every game, on the other hand, is basically dishonest, and the outcome has a dramatic, as distinct from merely exciting, quality. As pointed out in Chapter 3, all games have their origin in the simple childhood game of 'Mine Is Better Than Yours', easily observable in any group of four-year-olds. It was then, as it is now, designed to bring a little momentary relief from the burden of the not ok position. As in the more sophisticated grown-up versions, it is ulterior in that it does not express what is really felt. When the little person says, 'Mine is better than yours', he is really feeling, I'm not as good as you'. It is an offensive defence. It is protective in that it seeks to maintain homeostasis. It also has a pay-off, as do games grownups play. When 'Mine Is Better Than Yours' is pushed far enough, the game ends with a hard shove, a slapped face, or devastating evidence of some sort that 'It is not: mine's better.' This then puts the little person back in his place, it has been proved again that I'm not ok, and in the maintenance of this fixed position there is a certain miserable security. This is the essence of all games. Games are a way of using time for people who cannot bear the stroking starvation of withdrawal and yet whose not ok position makes the ultimate form of relatedness, intimacy, impossible. Though there is misery, there is something. As the comedian said, 'It's better to have halitosis than no breath at all.' It is better to be roughed up playing games than to have no relationship at all. 'The developing [child] is more likely to survive in the warmth of wrath and to suffer blight in the chill of indifference,' wrote Dr Richard Galdston, of abused children. Thus, games provide benefits to all the players. They protect the integrity of the position without the threat of uncovering the position. To further clarify the nature of games we shall report the moves in one game, 'Why Don't You, Yes But'. The players are Jane, a young career woman, and her friend. (This game frequently is played in the helping situation, the clergyman's study, the psychiatrist's office, or the kitchen of a longsuffering coffee mate.): Jane: I am so plain and dull that I never have any dates. Friend: Why don't you go to a good beauty salon and get a different hairdo? Jane: Yes, but that costs too much money. Friend: Well, how about buying a magazine with some suggestions for different ways of setting it yourself? Jane: Yes, but I tried that - and my hair is too fine. It doesn't hold a set. If I wear it in a bun, it at least looks neat. Friend: How about using makeup to dramatize your features, then. Jane: Yes, but my skin is allergic to makeup. I tried it once and my skin got rough and broke out. Friend: They have lots of good new nonallergenic makeups out now. Why don't you go see a dermatologist? Jane: Yes, but I know what he'll say. He'll say I don't eat right. I know I eat too much junk and don't have well-balanced meals. That's the way it is when you live by yourself. Oh, well, beauty is only skin deep. Friend: Well, that's true. Maybe it would help if you took some Adult Education courses, like in art or current events. It helps make you a good conversationalist, you know. Jane: Yes, but they're all at night. And after work I'm so exhausted. Friend: Well, take some correspondence courses, then. Jane: Yes, but I don't even have time to write letters to my folks. How could I ever find time for correspondence courses? Friend: You could find time if it were important enough. Jane: Yes, but that's easy for you to say. You have so much energy. I'm always dead.Friend: Why don't you go to bed at night? No wonder you're tired when you sit up and watch The Late Show' every night. Jane: Yes, but I've got to do something fun. That's all there is to do when you're like me! Here the discussion has gone full circle. Jane has systematically knocked down every one of her friend's suggestions. She begins with the complaint that she is plain and dull, then ends up begging the question with the final reason: she is plain and dull because 'that is the way I am'. Her friend finally gives up in defeat and perhaps finally stops coming over, further underlining Jane's not ok. This 'proves' to Jane that there indeed is no hope for her - she can't even keep the friends she has, and this justifies her indulging in still another game, 'Ain't It Awful'. The benefit to Jane is that she doesn't have to do anything about herself because she has repeated proof that nothing can be done. 'Why Don't You, Yes But' can be played by any number, according to Berne: One player who is 'it', presents a problem. The others start to present solutions, each beginning with 'Why Don't You'. To each of these the one who is 'it' objects with a 'Yes But'. A good player can stand off the rest of the group indefinitely, until they all give up, whereupon 'it' wins. Since all the solutions, with rare exception, are rejected, it is apparent that this game must serve some ulterior purpose. The 'gimmick' in 'Why Don't You, Yes But' is that it is not played for its ostensible purpose (an Adult quest for information or solutions) but to reassure and gratify the Child. A bare transcript may sound Adult, but in living tissue it can he observed that the one who is 'it' presents herself as a Child inadequate to meet the situation; whereupon the others become transformed into sage Parents anxious to dispense their wisdom for the benefit of the helpless one. This is exactly what 'it' wants, since her object is to confound these Parents one after another. (This is a latter-day version of 'Mine's Better Than Yours', which denies the real conviction, You Are Better Than I.) As the game ends, all those who offered advice are dejected, having failed in helping 'it', and 'it' has proved the point that her problem really is insoluble, which makes it possible for her to indulge her Child in a new game of 'Ain't It Awful'. That's the way it is and that's the way I am (and therefore I don't have to do anything about it, for, as we have just seen, nothing can be done). Berne describes about three dozen games in Games People Play. His games titles are colloquial, and most of them, with semantic precision, put the finger on the central characteristic of the game, as: 'Ain't It Awful'; 'If It Weren't for You, I Could'; 'Let's You and Him Fight'; and 'Now I've Got You, You Son of a Bitch'. Because the titles are colloquial, they frequently bring a laugh. The fact is games are not funny. They are defences to protect individuals from greater or lesser degrees of pain growing from the not ok position. The popularity of Berne's game book has given rise in many sophisticated circles to a new pastime of game calling. The concept of games can be a useful therapeutic tool when used in combination with a prior applied understanding of P-A-C; but in the absence of such insight the game concept, particularly game calling, can simply be another way to be hostile. People with an understanding of P-A-C can use an academic discussion of games by applying it to themselves; but to be 'called' on a game by another person, in the absence of insight or true concern, most often produces anger. It is my firm belief from long observation of this phenomenon that game analysis must always be secondary to Structural and Transactional Analysis. Knowing what game you are playing does not, ipso facto, make it possible for you to change. There is danger in stripping away a defence without first helping a person to understand the position - and the situation in childhood in which it was established - which has made this defence necessary. Another way of stating this is that if only one hour were available to help someone, the method of choice would be a concise teaching of the meaning of P-A-C and the phenomenon of the transaction. This procedure, I believe, holds more promise for change in short-term treatment than game analysis. Summarily, we see games as time-structuring devices which, like withdrawal, rituals, activities, and pastimes, keep people apart. What then can we do with time in a way which does not keep us apart? George Sarton observed: 'I believe one can divide men into two principal categories: those who suffer the tormenting desire for unity and those who do not. Between these two kinds an abyss - the "unitary" is the troubled; the other is the peaceful.' For many thousands of years man's existence has been structured preponderantly by withdrawal, ritual, pastimes, activities, and games. Scepticism about this assertion could perhaps best be met by a reminder of the persistent recurrence throughout history of war, the grimmest game of all. The majority of men have helplessly accepted these patterns as human nature, the inevitable course of events, the symptoms of history repeating itself. There has been a certain peace in a resignation of this sort. But, as Sarton suggests, the truly troubled people of history have been those who have refused to resign themselves to the inevitability of apartness and who have been driven on by a tormenting desire for unity. The central dynamic of philosophy has been the impulse to connect. The hope has always been there, but it has not overcome the intrinsic fear of being close, of losing oneself in another, of partaking in the last of our structuring options, intimacy. A relationship of intimacy between two people may be thought of as existing independent of the first five ways of time structuring: withdrawal, pastimes, activities, rituals, and games. It is based on the acceptance by both people of the I'm ok - you're ok position. It rests, literally, in an accepting love where defensive time structuring is made unnecessary. Giving and sharing are spontaneous expressions of joy rather than responses to socially programmed rituals. Intimacy is a game-free relationship, since goals are not ulterior. Intimacy is made possible in a situation where the absence of fear makes possible thefullness of perception, where beauty can be seen apart from utility, where possessiveness is made unnecessary by the reality of possession. It is a relationship in which the Adult in both persons is in charge and allows for the emergence of the Natural Child. In this regard the Child may be thought of as having two natures: the Natural Child (creative, spontaneous, curious, aware, free of fear) and the Adaptive Child (adapted to the original civilizing demands of the Parent). The emancipation of the Adult can enable the Natural Child to emerge once more. The Adult can identify the demands of the Parent for what they are -archaic - and give permission to the Natural Child to emerge again, unafraid of the early civilizing process, which turned off not only his aggressive antisocial behaviour but his joy and creativity as well. This is the truth that makes him free - free to be aware again and free to hear and feel and see in his own way. This is a part of the phenomenon of intimacy. Thus the gift of a handful of primroses may more readily be a spontaneous expression of love and joy than the expensive perfume from I. Magnin on the socially important anniversary date. The forgotten anniversary date is not a catastrophe for the intimate husband and wife, but it very often is for those whose relationship exists by virtue of ritual. The question is frequently asked: Are withdrawal, pastimes, rituals, activities, and games always bad in a relationship? It is safe to say that games nearly always are destructive, inasmuch as their dynamic is ulterior, and the ulterior quality is the antithesis of intimacy. The first four are not necessarily destructive unless they become a predominant form of time structuring. Withdrawal can be a relaxed, restorative form of solitary contemplation. Pastimes can be a pleasant way of idling the social motor. Rituals can be fun - birthday parties, holiday tradition, running to meet Dad when he's home from work - in that they repeat again and again joyous moments which can be anticipated, counted on, and remembered. Activities, which include work, not only are necessities of life but are rewarding in and of themselves, as they allow for mastery, excellence, and craftsmanship and the expression of a great variety of skills and talents. However, if there is discomfort in a relationship between two people when these modes of time structuring cease, it is safe to say there is little intimacy. Some couples programme their entire time together with frantic activity. The activity itself is not destructive unless the compulsion to keep busy is one and the same as the compulsion to keep apart. The question now arises: If we strip ourselves of the first five ways of time structuring, do we automatically have intimacy? Or do we have nothing? There seems to be no simple way to define intimacy, yet it is possible to point to those conditions which are most favourable for its appearance: the absence of games, the emancipation of the Adult, and the commitment to the position I'm ok-you're ok. It is through the emancipated Adult that we can reach out to the vast areas of knowledge about our universe and about each other, explore the depths of philosophy and religion, perceive what is new, unrefracted by the old, and perhaps find answers, one at a time, to the great perplexity, 'What's the good of it all?' An elaboration of this idea will follow in Chapter 12. CHAPTER 8: P-A-C and Marriage A friend of mine tells the following story about something that happened when he was a little boy. At the end of a meal his mother announced to the brothers and sisters, who numbered five, that dessert would be the remainder of a batch of her special home-made oatmeal cookies, whereupon she procured the cookie jar and set it on the table. There followed a noisy scramble by the children to get into the jar, with the littlest brother, age four, last, as usual. When he got to the jar he found only one cookie left, and it had a piece missing, whereupon he grabbed it and tearfully threw it to the floor in a rage of despair, crying, 'My cookie is all broke!' It is the nature of the Child to mistake disappointment for disaster, to destroy the whole cookie because a piece is missing or because it isn't as big, as perfect, or as tasty as someone else's cookie. In his family the anecdote lived as a standard retort to further complaints, 'What's the matter, your cookie broke?' This is what happens when marriages break. The Child takes over in one or both partners, and the whole marriage is shattered when imperfections begin to appear. It has long been recognized that the best marriages grow when both partners have similar backgrounds and similar reality interests. One of the most helpful ways to examine similarities and dissimilarities is the use of Transactional Analysis in premarital counselling to construct a personality diagram of the couple contemplating marriage. The aim is to expose not just the obvious similarities or dissimilarities but to undertake a more thorough inquiry of what is in the Parent, Adult, and Child of each partner. A couple who enters into such an inquiry might be said to have already a lot in their favour, inasmuch as they take marriage seriously enough to take a long look before they leap. However, one of the partners, having serious doubt about the soundness of the alliance, may undertake such an inquiry on his own. First we compare the Parent of each. We then undertook an inquiry into the strength of the Adult in each and an assessment of their reality interests. We then turned to an examination of the Child in each. The Establishment of Goals A ship with no destination drifts and is carried along by the prevailing tides, now up, now down, groaning and creaking in the high seas, tranquil and lovely in the calm. It does exactly as the sea does. Many marriages are like this. They stay afloat but they have no direction. The priority input in their decision making is, What are other people doing? They conform to their social circle in attire, housing, raising children, values, andthinking. 'As long as others are doing it, it must be OK,' is their standard of what to do. If 'everyone' is buying a certain kind of luxury automobile, they also will buy one, even if their hire-purchase commitments already constitute a library of monthly bad news. They have not built their own set of independent values concerned with their own particular realities and therefore frequently end up disillusioned and in debt. Only the Adult can say 'no' to the Child's clamouring for something bigger, better, and more in order to feel more ok. Only the Adult can ask the question, If four pairs of shoes make you happy, will ten pairs make you happier? The rule is that each increment of material possessions brings less joy than the one that immediately preceded it. If one could quantify joy, it is likely that a new pair of shoes brings more happiness to a child than a new car brings to a grown man. Also, the first car brings more joy than the second, and the second more than the third. H.L. Mencken said, 'A man always remembers his first love. After that he begins to bunch them.' The Child in us needs bunches - as on Christmas morning: surrounded with gifts the child cries, 'Is that all?' A little boy was asked on a children's television programme what he got for Christmas. 'I don't know,' he said, distressed, 'there was too many.' An Adult examination of a family's realities can weigh whether or not the acquisition of a certain possession will be worth (in terms of joy) the mortgage, the department store bill, or the diversion of the money from something else. The Adult can also give in to the Child's need to collect bunches of possessions by taking up a hobby such as collecting stamps, coins, rare books, model railroad equipment, bottles, or rocks. The Adult can determine whether the expenditure for these collections is realistic. When it is, the 'bunching' is fun and harmless. If it is bankrupting the family, however (eg, collecting villas, sports cars, and original Picassos), the Adult may have to say 'no' to the Child's fun. Decisions regarding hobbies, possessions, where to live, and what to buy must be made according to a set of values and realistic considerations unique to the marriage. Agreement about these decisions is extremely difficult if goals for the marriage have not been established. A couple in treatment may learn to see the difference between Parent, Adult, and Child, but they are still on the same social sea, and if they do not chart a course, they will, despite all their insights, continue to follow the old ups and downs and fun and games. It takes more than knowing something to muster the power to cut through the social currents. It takes the establishment of and embarking upon a new course in the direction of goals arrived at by the Adult. Persons either set a new course or they fall back into the same patterns of drift. It does not matter how many charts they have. This is where the considerations of moral values, of ethics and religion, become important to the course of a marriage. A man and wife must undertake some fundamental inquiries about what they consider important in order to chart their course. Will Durant views the fundamental problem of ethics in the form of the question, 'Is it better to be good or to be strong?' {6} This question can be asked in many ways in the context of the marriage. Is it better to be kind or to be rich? Is it better to spend time with the family or to spend time in civic activities? Is it better to encourage your children to 'take it on the chin' or to 'hit back'? Is it better to live big today or hoard every penny in the bank for tomorrow? Is it better to be known as a thoughtful neighbour or to be known as a civic leader? These are questions which can lead to hopeless forensic entanglements unless they are asked by the Adult, for they are difficult even then. It is not enough to know what opinions the Parent in each partner contains in answer to these questions. It is not enough to know the Child needs the feelings of each. If the Parent or Child data is in disagreement, there must be some ethical standard accepted by both, which can give direction to the course of the marriage and value to all decisions that must be made. It has been said that 'love is not a gazing at each other, but a looking outward together, in the same direction'. The Parent and Child in each partner may lead backward to great divergence. Only through the Adult is convergence possible. Yet the goal 'out there' cannot be established without moral and ethical considerations. One of my frequent questions to a couple in an impasse over 'what to do now' is: 'What is the loving thing to do?' This is the reaching beyond scientific evaluation to the possibility of the evolution of something better than what has been before. What is 'being loving'? What is love? What kinds of words are 'should' and 'ought'? These questions are considered in depth in Chapter 12, 'P-A-C and Moral Values'. CHAPTER 9: P-A-C and Children The best way to help children is to help parents. If parents do not like what their children do, it is not the children alone who must change. If Johnnie is a problem, he is not going to improve by being taken from expert to expert, unless something is done about the situation at home. This chapter is written to help parents help children. 'Experts' cannot do the job parents can. This chapter has following subtopics that you can refer for more information on parenting and child rearing. - Where to Start - The School-Age Child - Preadolescents in Treatment - The Adopted Child - The Battered Child - Teaching P-A-C to the Retarded Summarily, we may say that the solution to the problems of all children, regardless of their situation, is the same solution that applies to the problems of grownups. We must begin with the realization that we cannot change the past. We must start where we are. We can only separate the past from the present by using the Adult, which can learn to identify the recordings of the Child with its archaic fears and the recordings of the Parent with its disturbing replay of a past reality. Parents who have learned to do this through their understanding and application of P-A-C will find themselves able to help their children differentiate between life as they observed it or were taught it (Parent), life as they felt it (Child), and life as it really is and life as it can be (Adult). They will find that this same procedure will be of the greatest value in the period of change that lies ahead, the years of adolescence, which we examine in the next chapter. CHAPTER 10: P-A-C and Adolescents One day a sixteen-year-old member of one of my adolescent groups reported the following incident: 'I was standing on the street corner and the light was red. My Parent said, "Don't cross", my Child said, "Go ahead anyway", and while I was debating what to do the light turned green.' The years of adolescence are like this. Teenagers are confronted with big and little decisions. Yet, often they seem to have to wait for circumstances to make their decisions for them, because they are not really free to decide for themselves. Their brain is nearing its prime development. Their body is mature. But legally and economically they are dependent, and their attempts at emancipated action are frequently undercut by the realization that they can't really make their own decisions anyway, so what's the use of making good decisions. They feel they may as well drift along through adolescence and wait for the light to turn green. The Adult does not develop under these circumstances. Suddenly when they are legally emancipated they feel adrift, they don't know what they want to do, and many of them pass time hoping something will happen, someone will come along, somehow something will turn them on. Yet, at this point, one-fourth of their life has passed. Because of external and internal pressures the transactions of the teenager frequently fall back into the old Child-Parent patterns. In adolescence the feelings of the Child replay in greatly amplified form as the hormones turn on and as the adolescent turns away from his parents as the principal source of stroking to his own age group for stroking of a new kind. The not ok tapes come on with increasing frequency, but the coping techniques learned in childhood to minimize the not ok now can be dangerous. The seductive cuteness of the little girl must now be brought under control to guard against new developments, both external and internal. The 'mine is better' boisterousness of the little boy must be modified in the name of manners as the adolescent learns the painful process of self-control. Communication has to be relearned and revised. The adolescent is pushed out on the stage with a new manuscript in his hands, which he has never read, and the lines don't come off too well at first. He is like a plane shooting ahead at full speed, between converging cloud layers. Below, and rising fast, are the boiling clouds of sexual urges and the rebellious struggling for independence; above are the hovering and lowering clouds of parental anxiety and disapproval. He feels things are closing in, and he desperately looks for an opening. The central difficulty is that he and his parents often are still working under the terms of the old Parent-Child contract. As much as he sees himself as a grownup, he still feels like a child. Parents may suggest what they believe to be a perfectly reasonable course of action and are frustrated, baffled, and hurt over his angry rebuttal, hooking their Child. Often the problem is that he mistakes his external parents for his internal Parent. He cannot hear the mother and father of his teenage years because the old tapes play back the mother and father of the three-year-old, with all the hand slapping, horrified looks, and thunderous 'no's' of those early years. The external stimulus hits the Parent, Adult, and Child of the teenager simultaneously. The question is, Which one will handle the transaction? Throughout childhood the Child is continually activated, even though there are, depending on the individual, a vast number of Adult transactions. The Child is extremely vulnerable, or 'hookable', in this emotionally charged time of life. Whereas the Child responses of the little person could quickly be rationalized as 'childish', those same responses now become threatening and disintegrating to the parents. The door slamming of the five-year-old can be rather terrifying if the slammer is a six-foot-tall fifteen-yearold. The sulk of the little girl is seen as ugly and infuriating in the teenager. What may have been seen in the little boy as a habit of 'making up stories' appears in the adolescent under the heading of 'lies'. The early recordings are the same. Many of the coping techniques of the Child continue in the adolescent years. Bertrand Russell writes of this: So many things were forbidden me that I acquired the habit of deceit, in which I persisted up to the age of twenty-one. It became second nature to me to think that whatever I was doing had better be kept to myself, and I have never quite overcome the impulse to hide what I am reading when anybody comes into the room. It is only by a certain effort of the will that I can overcome this impulse. This 'effort of the will' is the Adult. The Adult can identify the old recordings. It can also recognize the inappropriateness and ineffectiveness of their replay in adolescence. The central need, then, is to keep the Adult in control of this adult-size body so that the realities in the present can gain priority over the realities of the past. What constitutes the central work of treatment is the freeing up of the Adult in both the teenager and his parents in order that an Adult-Adult contract may be drawn. Without an emancipated Adult, life is an unbearable double bind for both. The problem of the adolescent is that inside he has a strong troublemaking Parent, and he is forced to live in the setting in which that Parent developed, where the Parent within is reinforced by the parents without. As parents become threatened and fearful, they find themselves turning more and more frequently to their own Parent for Grandparent solutions, which can be as inadequate as trying to make a jet plane run with hay. Both the parents and the teenager are so threatened that the Adult is decommissioned in both. The teenager acts out Child feelings and the parents, fearful of letting their feelings take over, most often turn the transaction over to the Parent (grandmother and grandfather). No common reality exists without an Adult-Adult contract, and communication ceases. ... Chapter ends with the para: Through the troubling years of adolescence, when young people sometimes seem to turn a deaf ear to the words of their anxious parents, there nevertheless is a hunger to hear and experience reassurances of Mum and Dad's love and concern. The longing for this reassurance was stated in a compelling way recently by my five-year-old daughter, Gretchen. When Mother arrived on the scene, Gretchen was maintaining a precarious balance as she walked along the narrow edge of a brick flower enclosure. Mother said, 'You be careful or you'll fall down into those flowers.' Gretchen said, 'Do you care about the flowers or about me?' The 'five-year-old' in the adolescent asks the same question, only he does not state it in so many words. Parents who are sensitive to this unstated plea and who, through acts of love, concern, restraint, and respect, demonstrate repeatedly It Is You We Care About will find the years of adolescence can produce rewards and surprises far beyond their expectations. CHAPTER 11: When Is Treatment Necessary? If a person sprains an ankle he can hobble along and eventually the ankle will get well. He still has some use of it while he hobbles. If he breaks a leg he needs support for. it while the bone is healing. One problem is an impairment. The other is crippling. Medical attention would have been helpful in the first case; it was imperative in the second. We can view the need for treatment of emotional problems in somewhat the same way. A person's Adult may be impaired by old recordings from the past, but he may manage to get over difficulties or through problems without treatment. Treatment could make it easier. But he manages. For some people, however, the Adult is impaired to the point where they cannot function. They are crippled by repetitious failure or immobilized by guilt. Frequently there are physical symptoms. Mothers cannot function as mothers, workers cannot do their job, children give up at school, or some persons' behaviour becomes inappropriate to the point where they break the law. For these people treatment is required; yet everyone could benefit from it. All persons can become Transactional Analysts. Treatment simply speeds the process. Treatment with Transactional Analysis is essentially a learning experience through which an individual discovers how to sort out the data that goes into his decisions. There is no magic applied by an omnipotent expert. The therapist uses words to convey what he knows and uses in his own transactions to the person who comes into treatment, so he can know and use the same technique. One of my psychiatrist friends said, 'One of the best Transactional Analysts I know is a truck driver.' The goal is to make every person in treatment an expert in analysing his own transactions. Many forms of psychiatric treatment are quite different. The public image is assuredly different. For this reason the decision to go to a psychiatrist generally is not made without a great deal of internal debate. Many patients experience unpleasant feelings over the thought of exposing themselves to someone, even though that someone is an 'expert' or professional helper, such as a psychiatrist. As the patient opens the door to the office for the first time, he frequently feels alone, fearful, and ashamed over the implication of failure. Even if the Adult in the individual gets him to the psychiatrist's office, the Child soon takes over and a Parent-Child situation develops. The patient's Child expresses feelings and anticipates a relationship with the psychiatrist's Parent in the transactions of the first hour. The psychoanalysts refer to this as transference - that is, the situation provokes a transfer of feelings and related behaviour from the past, when the patient was a child, into the present, in which the Child in the patient responds as it once did to the authority of the parent. This unique transaction is fairly common in life, and there are elements of it present in any contact with authority, as, for instance, when one is stopped by a highway patrolman. Psychoanalysts maintain that the patient has improved when he has succeeded in avoiding this kind of transfer of feelings from childhood. At this point in analysis, the patient does not have to pick and choose what he is going to reveal about himself to his analyst. In other words, the patient no longer must be afraid of the analyst's Parent. This is referred to in traditional psychoanalysis as overcoming resistance. In Transactional Analysis we bypass much of the retarding effects of transference and resistance by the mutually participant format and content of P-A-C. The patient soon finds he is relating on equal terms to another human being to whom he has come for help, a human being interested in advancing the patient's knowledge of himself at once so that, as quickly as possible, he can become his own analyst. If the patient is hampered by transference and resistance feelings, these are handled directly with him in the initial hour after he has become acquainted with Parent, Adult, and Child. This chapter has following subtopics that you can refer for more specific information. - Diagnosis - Why Group Treatment? CHAPTER 12: P-A-C and Moral Values % You tell your six-year-old son to go back out there and punch that kid in the nose the 'way he punched you!' Why? % You march in a demonstration protesting the Vietnam war. Why? % You give one-tenth of your income to your church. Why? Every day most people make decisions of this kind. They are all moral decisions, or decisions of right and wrong. Where does the data which goes into these decisions come from? From the Parent, Adult, and Child. After you have examined all of your own Parent data, kept some and rejected some, what do you do if you do not feel you have the necessary guides for decision making? Abdicate? Once you have an emancipated Adult, what do you do with it? On moral questions, can you figure things out for yourself - or do you have to go ask an 'authority'? Can we all be moralists? Or is that for very smart and wise people? If we don't seem to be doing very well, where can we go for new data? Where are we deficient? What kinds of reality can the Adult examine?Reality is our most important treatment tool. Reality, understood through the study of history and the observation of man, is also the tool by which we construct a valid ethical system. We are not reasonable, however, if we assume that the only reality about man is that within our own personal experience or comprehension. Reality, for some people, is broader than it is for others, because they have looked more, lived more, read more, experienced more, and thought more. Or their reality simply is different from someone else's reality. Our need for direction in the journey through life is similar to the navigational problem of an airplane pilot. Pilots in the early days of aviation flew 'by the seat of their pants' and relied on their vision, comparing what they saw below them - rivers, inlets, railroad tracks, and towns - with the maps they had spread before them. This, of course, was unreliable when vision was obstructed, even for a short time. Therefore, navigational aids were devised to 'take a fix' on two points. (The two points are special radio stations. Each emits a signal informing him of the compass radial his plane is on in relation to the station.) He draws the two radials as lines on his map, and where the two lines cross is where he is. If he took a fix in only one direction he could not find his location. He might discover he was on the equator. But where on the equator? He would have to 'look' in another direction for the data to answer that question. I feel that many psychiatrists and psychologists have been guilty of 'one fix' treatment in that they have devoted all their time to looking at only one reality, the past history of the patient - what he did - and largely ignored an examination of the types of reality that might help him understand what he should do. We are hopelessly impoverished if we believe that the only realities that concern our mental health have to do with a state of affairs wherein 'I am So and So because when I was three years old Mother hit Father with my potty seat on Christmas Eve in Cincinnati.' Archaeology of this kind reminds me of H. Allen Smith's story about the little girl who wrote a thankyou note to her. grandmother for giving her a book about penguins for Christmas: 'Dear Grandmother, Thank you very much for the nice book you sent me for Christmas. This book gives me more information about penguins than I care to have.' We can spend a lifetime digging through the bones of past experience, as if this were the only place reality existed, and completely ignore other compelling realities. One such reality is the need for and existence of a system of moral values. The chapter has following subtopics that you can refer to for specifics: - What Is a Rational Code of Morality? - Is Agreement on Moral Values Possible? - The Worth of Persons - 'I Am Important, You Are Important' - 'It Won't Work!' - The Original Game Is the Original Sin - P-A-C and Religion - What Is a Religious Experience? - How Does a Religious Experience Feel? - People in Perspective - What Is Reality Therapy? The subtopic "People in Perspective" has these interesting lines: In a sermon I heard some time ago the following statistics were presented: If the 3 billion people of the world could be represented in a community of one hundred: Six would be United States citizens; ninety-four would be citizens of other countries. Six would own one-half of the money in the world; ninety-four would share the other half; of the ninety-four, twenty would own virtually all of the remaining half. Six would have 15 times more material possessions than the other ninety-four put together. Six have 72 per cent more than the average daily food requirement; two-thirds of the ninety-four would have below-minimum food standards, and many of them would be on a starvation diet. The life span of six would be seventy years. The life span of ninety-four would be thirtynine years. Of the ninety-four, thirty-three would come from countries where the Christian faith is taught. Of the thirty-three, twenty-four would be Catholic and nine would be Protestant. Less than one-half of the ninety-four would have heard the name of Christ, but the majority of the ninety-four would know of Lenin. Among the ninety-four there would be three communist documents which outsell the Bible. By the year 2000 one out of every two persons will be Chinese. We are deluded if we continue to make sweeping statements about God and about man without continually keeping before us the facts of life: the long history of the development of man, and the present-day diversity of human thought. This may be frightening data to some people. 'Hopeless!' they may cry. I rather like Teilhard's view. When asked once what made him happy, he said: I'm happy because the world is round.' The borders, corners, or angles are not physical, but psychological. If we remove the psychological fences erected to protect the not ok Child existent in every person, there are no barriers to prevent our living together in peace. ... The chapter ends with the lines: In Transactional Analysis we have these words. The patient begins by activating his Child, and viewing the therapist as Parent. In the initial hour, Parent, Adult, and Child are defined, and these words are then used to define the contract, or mutual expectations from treatment. The therapist is there to teach and the patient is there to learn. The contract is Adult-Adult. If the patient is asked, 'What happened?" he can tell what happened. He has learned to identify his own Parent, Adult, and Child. He has learned to analyse his transactions. He has acquired a tool to free up and strengthen his Adult, and only this Adult can be responsible. I agree wholeheartedly with Glasser's central focus of responsibility, just as I agree with the ideal of the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule. The reality that concerns me, however, is why these admonitions do not routinely produce responsible persons. To simply restate them in new ways is not going to do the job. We cannot produce responsible persons until we help them uncover the I'm not ok - you're ok position which underlies the complicated and destructive games they play. Once we understand positions and games, freedom of response begins to emerge as a real possibility. As long as people are bound by the past, they are not free to respond to the needs and aspirations of others in the present; and 'to say that we are free', says Will Durant, 'is merely to mean that we know what we are doing'. CHAPTER 13: Social Implications of P-A-C The chapter has following subtopics that one can refer to for specifics: - How Irrational Are We Capable of Being? - Is This Younger Generation Different? - Analysing International Transactions - Winners and Losers From the subtopic: How Irrational Are We Capable of Being? Stanley Milgram's research at Yale begins to put a scientific foundation beneath Cook's deductions around obedience. Milgram carried out a series of psychological experiments in obedience. He took a sample cross-section of the adult (aged twenty to fifty) male population of Bridgeport, Connecticut, from blue-collar workers through professionals. The experiment was to determine how much punishment one person would inflict on another when so ordered, but it was deceptively presented as a scientific study by 'Bridgeport Research Associates' on learning techniques. The subjects were selected at random, paid four and a half dollars for their time. A learner was strapped into an 'electric chair' after the subject (a teacher) had experienced a sample shock of 45 volts to convince him of the authenticity of the instrument. Then from an adjoining rthe subject (teacher) delivered a shock of increasing intensity for each wrong answer. Actually the learner was not shocked but his responses were a standardized tape recording of murmurs, gasps, pleas, and shrieks matched to the ascending voltage. The answers were prearranged by the experimenter, so the only limiting factor preventing the teacher from delivering the maximum intensity of the shock machine was his compassion for a human being in pain. The conflict for the teacher (Mr Everyman) was obedience to the authoritative system versus his belief that he should not hurt another person. What percentage of the so-called teachers went the full route and gave the maximum shock? But before you guess, listen to the voice of Mr Everyman at the switch: 150 volts delivered: 'You want me to keep going?' (command) 165 volts delivered: That guy is hollering in there. There's a lot of them here. He's liable to have a heart condition. You want me to go on?' (command) 180 volts delivered: "He can't stand it I'm not going to kill that man in there! You hear him hollering? He's hollering. He can't stand it. What if something happened to him? You know what I mean? I mean, I refuse to take the responsibility.' (the experimenter Accepts The Responsibility) 'All right.' 195 volts, 210, 225, 240, and so on. The subject (teacher) unfailingly obeyed the experimenter. What percentage of the almost one thousand teachers went the whole route? Estimate before you let your eyes stray ahead. A group of forty psychiatrists who studied the project predicted one-tenth of one per cent. In the actual experiment, sixty-two per cent obeyed the experimenter's commands fully. What did you guess? Milgram concluded: 'With numbing regularity good people were seen to knuckle under the demands of authority and perform actions that were callous and severe. Men who in everyday life are responsible and decent were seduced by the trappings of authority, by the control of their perceptions, and by the uncritical acceptance of the experimenter's definition of the situation into performing harsh acts. The results, as seen and felt in the laboratory, are to this author disturbing. They raise the possibility that human nature, or more specifically, the kind of character produced in American democratic society, cannot be counted on to insulate its citizens from brutality and inhumane treatment when at the direction of a malevolent authority.' The implications of this experiment are indeed frightening if we view the results as having only to do with something irredeemable in human nature. However, with Transactional Analysis we can talk about the experiment in a different way. We can say that 62 percent of the subjects did not have a freed-up Adult with which to examine the authority in the Parent of the experimenters. Undoubtedly one unexamined assumption was: Whatever experiments are necessary for research are good. This is perhaps the same assumption that helped 'reputable' scientists participate in the laboratory atrocities in Nazi Germany.