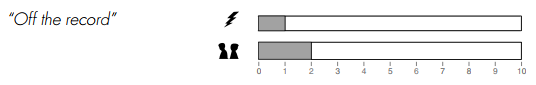

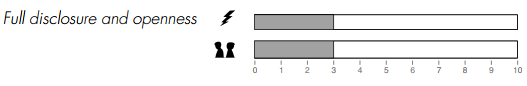

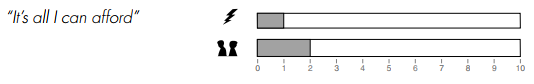

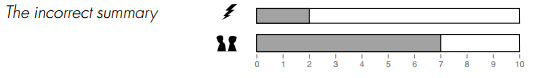

“Experience is not what happens to you; it’s what you do with what happens to you.” - Aldous Huxley The decisions you take and the way you behave during your negotiations will be influenced by how much power you think you have and by the way your own values or ethics influence your behavior. The tactics you employ will be limited by both how much power you have, whether you have a short- or long-term relationship to consider and this may influence how ethical you choose to be during your negotiations. The dilemma of where the value of fairness fits into negotiation has challenged many organizations. For instance, some organizations who hold strong views on being fair and reasonable may take exception when faced with a trading partner who behaves in a manipulative or irrational manner. On principle, they will not tolerate the behavior and will exit the relationship. RECOGNIZING THE PROCESS AND THE GAMESMANSHIP IN PLAY The way the balance of power is split, and how it shifts with time and circumstance, means you cannot expect agreements always to be, or appear to be, balanced and fair, or even consistent. You can, however, work towards getting the best possible deal given the circumstances you face. Some, faced with such situations, turn to tactics and some become victims of the tactics in play. The Complete Skilled Negotiator sees them for what they are and where necessary uses counter tactics to neutralize their effects. I am not implying here what is right or wrong. You will conduct business based on values that are probably different from those of others. This does not make yours right or wrong; it does not make the other party’s values right or wrong. It simply means that our interpretation, understanding, and use of tactics will differ from others as the implications of making use of them will differ based on your circumstances and our view of what acceptable behavior is made up of. As a general rule, negotiations that focus on short-term agreements with parties with whom we have no ongoing relationship, or prospect of one in the future, are more inclined to gravitate towards value distribution (1–6 o’clock) negotiations. Tactics tend to be more readily used in these styles of negotiations as the relationships involved tend not to be long term. A QUESTION OF CHOICES AND PERSONAL STYLE The concept of “fairness” is exploited by some negotiators through the use of tactics. Western democratic societies are designed to offer freedom and choice. This serves to remove the notion of being controlled, and, as long as we have choices, many perceive this as freedom and fairness. So choices are designed to signal fairness. However, if like governments you are controlling the options or choices, then you have the power to influence the outcome. However, if you are overtly unfair in the choices you provide others, trust will be difficult to build and, with no trust, it is difficult to negotiate collaboratively (7–12 o’clock on the clock face). Social laws, or the unwritten laws of society, influence our view of what is fair and reasonable under whatever circumstances. Business partnerships, where there is a need to maintain productive relationships and the need to jointly problem solve or develop incremental value by working together, require at least some level of trust. To be perceived to be fair in business, you need to offer choices: choices that are not so one-sided that they quickly become regarded transparent and unfair. Personal attributes Your personal values and how they influence your behavior will have a powerful bearing on where you and the other party gravitate to on the clock face. They can, if not managed, directly influence whether you build relationships or whether you enter into combat each time you seek to agree terms. Below are some of the personal attributes to consider and the influence they will exert during your negotiations. Trust in business has to be earned and is easily broken. It implies that you are good for your word. If you say something will happen, it happens, consistently. You approach the conversation from their perspective, sharing their concerns and working on the problems that you both identify, together. It does not mean that you have to pay by conceding on terms, by offering personal favors or by being more transparent with your interests. Respect comes from being firm, consistent and reliable. If you are too flexible or concede too easily, the other party will regard you as being weak. In negotiation, everything is possible, but difficult. The fact that it is difficult ensures that the work you put into the deal, engineering the terms, and moving reluctantly, attracts respect for you, your position and your credibility. Integrity comes from consistency. This can present issues for negotiators who are too focused on not being unpredictable. Maintaining confidentiality and being reliable, in that you follow through with your commitments, also help promote integrity, which in some relationships or even industries is critical if business is to take place at all. Honesty. You never need to lie in negotiation. You don’t need to tell them what you won’t do. Focus on what you will do. Think “how” or “on what basis could we, or could they?” By telling them what you are prepared to do you are at least maintaining honesty. By telling them you are prepared to pay $100 when you know that you could pay $150 is not lying. Don’t confuse the process of negotiation with lying and telling the truth. If you lie in negotiation, you could be taking unnecessary risks, and in some cases completely compromising relationships, however, don’t expect everyone to adhere to this discipline. Consideration of the needs of the other party. If you don’t understand these you are not ready to negotiate. Your planning, preparation, research, and exploration meetings are all there to help you to establish their position, motives, priorities, and interests. To place a value on these you have to understand the deal the way they do business from inside their head. Considering the facts will allow you to remain sensitive to the issues and respectful where necessary. Empathy is about understanding and appreciating the challenges from their perspective, but never compromising because of such understandings. Responsibility. It is you who will conduct your negotiations and you who will make the decisions with the authority limits you have been given. The more trust that genuinely exists within your relationships, the more scope you have to open up the agenda and work together creatively. This will only come about if you cultivate the necessary climate and discussions. Risky attributes Openness. This can be dangerous in negotiation. Information is power and the more you share with the other party, the more you will expose yourself. Be open but stay within the parameters that you set yourself. If you don’t understand this from the outset you will place yourself in a very vulnerable position. Compassion. In the tough world of business your job is to maximize opportunity. You will do this with those you can work with and rely on, and who remain highly competitive. This is a capitalist market we operate in. Compassion, like generosity, has to take a back seat once a negotiation commences unless of course you have a longer-term plan in mind. WHAT ARE TACTICS? When do tactics usually come into play? Tactics tend to be used more frequently when one party has more power than the other and tries to take advantage of it. Tactics are also more frequently used where the nature of the negotiation is based on value distribution and the focus is on taking as much value off the table as possible. Dealing with tactics and when to use them There are dozens of books written on negotiation that present tactics as the basis of negotiation. They are given names that serve to explain the approach: “The Russian front,” “The Trojan horse,” and so on. The most important thing about tactics is to recognize them for what they are. • They are neither clever nor sophisticated. • They are designed to apply pressure and usually by those who can because they have enough power, or think they have enough power, to do so, or those who think they are clever enough to do so without any consequences. However, they are used with such regularity that one has to recognize and understand them, adapt to them, and, where necessary and appropriate, even use them. To help with this I have categorized a range of tactics using a simple scale of 1–10 (1 is low and 10 is high) against two factors: • Power required: the amount of power you will need to have or be perceived to have relative to the other party for this tactic to work. • Relationship erosion: the degree to which your relationship or any trust that may exist within it will be eroded, if the tactic once used becomes obvious or transparent to the other party. For the purpose of outlining some of the more widely used tactics, I have placed them into one of seven categories. These are: 1. Information - “The hypothetical question” - “Off the record” - Full disclosure and openness - Why? 2. Time and momentum - Deadlines - “And just one more thing” - Denied access - Time constraint - The auction - Time out 3. Fear or guilt - Physically disturbing them - Good guy, bad guy - The Russian front - Personal favor - Guilty party - The social smell - Silence 4. Anchoring - Sow the seed early - The power statement - The mock shock - The professional flinch - The broken record 5. Empowerment - Higher authority - Defense in depth - Use of official authority - “It’s all I can afford” - Onus transfer - Off-limits - New faces 6. Moving the costs around - The building block technique - Wipe the proposal off the table without saying no - Linking the issues - Side issue or red herring - The slice 7. Deceit - Trojan horse - The incorrect summary - Deliberate misunderstanding - The dumb foreigner - The loss leader 1. Information Information is power. The more information you have about the options, circumstances, and priorities of the other party, the more powerful you become. The Hypothetical Question “What if...” and “Suppose that...” questions used during the exploratory and closing stages can help you to work out the degree of flexibility the other party is prepared to offer, or the relative value of the issues being discussed. For example: “What if we were to ‘hypothetically’ increase the order after 3 months, how might that change the fee structure?” There may be no intention of doing so, but the idea is to test assumptions, gain insights and untimately trade more effectively later on during your negotiation. It can be used to explore possibilities, especially where deadlock is looming. Off the record This is where one party asks the other for a view, a comment, or to simply share an insight, in the name of helping both parties make progress. Their intentions may be genuine, but the information is sought for one reason only: to get inside your head. You may choose to use it yourself for the same reason. However, when asked for an “off the record” meeting, always remember the real risks you carry. Any indications, signals, comments, or even attitudes you imply will be read into. There is no such thing as an “off the record” meeting. Anything you tell them or their business will quickly make its way to the decision maker and is likely to influence the outcome. By all means make use of “off the record,” but do not get used by it. Full disclosure and openness When a request for full disclosure is made before or during a meeting, there needs to be a reasonable degree of trust or mutual dependency before parties tend to agree. Even then it usually comes with conditions or limits: “We will share our data with you on the current site, but feel that extending this to our overall operation to be unnecessary,” is the type of response you will get. Some will say: “I’m going to be really open with you,” which usually means they are not. This is also the case when people use such words as “really,” “actually,” “genuinely,” “seriously,” “sincerely,” and, most common of all, “honestly.” Whenever I have heard these words in negotiation where people are under pressure, I have concluded that the truth has not been in play. Listen out for them and remain mindful of the longer-term implications of full disclosure. In reality, you can assume that something will usually be held back. The process of due diligence is used for very good reasons: to ensure the integrity of information provided is true and complete. "WHY?" This simple question can be used to challenge everything from interests, priorities, agenda items or even new proposals. It has been used as an effective way of establishing the thinking and importance of any issue or statement. Anyone can ask “why?”, which is why curious children ask it time after time in their quest for knowledge. The information you receive will always provide an insight, even if it’s something like: “We are not prepared to go into detail on that issue.” During exploration discussions, it’s worth asking why the other party is asking the very question that they are; and what insight this gives you into their thinking. 2. Time and momentum Time is the most powerful lever available to any negotiator. Time and circumstances affect the value of just about every product or service bought and sold around the world. If I was going to provide you with a full advertising plan to support your June election campaign, but could not actually start until June, my services would be deemed useless and without value. However, if the service could commence in during March, and run for 3 months peaking with tailored activity throughout June, the service could attract a premium. It’s the same service with a different time slot, which makes all the difference. So, understanding the time pressures of the other party is vital to you being able to optimize the leverage during your negotiations. How you communicate your own time pressures or use the other party’s time pressures to gain movement or agreement can be directly influenced by the tactics you use. "DEADLINES" “If you do not agree by Friday we will not be able to start the project in the timescales you have stipulated.” “We are closing the book on this one so we will need to know by this afternoon if you want to take part.” “If we can agree in principle today, I will ensure you get the business, subject to us ‘ironing out’ the terms.” The pressure that deadlines can exert means that some may not only use this tactic as a closing device, but also to provide you with the feeling of having “won.” Deadlines are used in many other ways, for example: “Because of changes in our business, after today’s deadline, any agreement will have to be signed off by my boss.” On some occasions, once the other party has established your deadlines they will employ this need as a trading variable. They will imply that the timing issue is not so critical to them. Be careful when providing total transparency relating to the implications of deadlines; it can be a highly effective and manipulative tool. "AND JUST ONE MORE THING" This is often used at the end of the negotiation when the deal is regarded as all but done. One party turns to the other just as you are about to shake hands and says: “Just one more thing, you will of course be including the flexible payment scheduling we discussed earlier?” They pause and wait with their hand held out. You think, I’m there, deal done, finished, closed. Do I now open up the discussion again, or worse still, compromise the agreement by saying “no, but I didn’t think that flexible payment scheduling was ever part of the terms we had agreed.” As you can see, this tactic has a higher relationship erosion factor. If the other party has either power or enough nerve, they will and should challenge the assumption by attaching a condition to the flexible payment scheduling in the same way they would have if it had been raised earlier during the formal discussions. "DENIED ACCESS" When you need to move discussions on, perhaps due to time pressure or the implications of deadlines, some will use denied access as a tactic. They simply ensure they are not available. They tell their colleagues and assistants to pass on the message they are in back-to-back meetings, out of town, away, or anything that ensures that you, the other party, cannot make progress until they are ready. One way of dealing with this situation when you are confident that denied access is in play is to leave a message for the other party, bringing your deadline artificially forward, adding that if the deadline passes without agreement, the deal is off or the terms on offer are time limited. Although risky, this buys you a window of opportunity between the deadline they think you are working to and the one actually in play. Another is to introduce a credible option, perhaps another party or option that you plan to take up and you need to let them know within certain timescales. If you don’t hear back you will place the order, reluctantly, elsewhere. Of course these options carry risks but often work as a way of unlocking the denied access tactic. "TIME CONSTRAINT" This is used where the other party introduces artificial time lines or deadlines, stating that their offer expires on a certain date. Further demands are then introduced as a consequence of the deadline not being met as “compensation” against the implications. Time constraints are also used where one party is near agreement on most of the terms, but the other decides to hold out for a better fee rate. They say: “We will give you one last chance to increase your offer. Please advise us by 5.30 pm on Friday of what this is, and we'll let you know if we are prepared to progress.” During the time that passes, which is aimed at fuelling uncertainty and doubt, the other party is often pressured into improving their final offer. "THE AUCTION" The bidding process is designed to create competition. The process is engineered and controlled by the organizers. As the bids increase, rational judgment is tested and for those with high egos, winning has been known to take over as the predominant driver of behavior. Time and momentum work against those willing to continue bidding, so a clear and absolute break point must feature as part of your planning if you are to enter such a process. "TIME OUT" When in doubt, for whatever reason, adjourn the meeting and take a time out to regroup. You need to understand the implications, risks, or fi nances if you are to maintain clarity and be able to work out how you are going to move forward. It is often used when new information comes to the fore, or if deadlock is looming and a need for a “fresh look” at the deal is needed. It’s also used when time is running out and one party chooses to put the other under pressure by removing themselves from the room until time pressures become critical. 3. Fear or guilt This next category raises the stakes in the relationship and heightens the risk. With high levels of power, threats are used in subtle ways to create movement. It is the fear of these threats or the fear of losing the deal that is played upon by those seeking to manipulate the power they have. "PHYSICALLY DISTURBING THEM" This is made up of a variety of non-violent but yet physical gestures which are introduced to unsettle and distract you. This can include leaning across the table to invade your personal space, sitting very close to you, or changing the seating pattern, so they are sat next to you. Seating positioned to face the sunlight or groups crammed into very small rooms are all part of the environment used to intimidate. Always remember that you are in charge and that includes your environment, so if it does not feel right, challenge it, question it and change it. You’ll attract respect for doing so and set the scene for equal respect in the meeting. "GOOD GUY, BAD GUY" This is typically used in team negotiations where one member of the team makes very high or irrational demands, and the other offers a more reasonable approach; or one is challenging and dismissive whilst their colleague presents themselves as far more understanding. The approach is designed to make the “good guys” appear reasonable, rational, and understanding, and therefore all the more agreeable. Essentially it’s using the law of relativity to attract cooperation. It’s transparent enough and certainly erodes any potential for trust, so ensure next time you are exposed to it that you see it for what it is. "THE RUSSIAN FRONT" As described by Gavin Kennedy in his book Everything is Negotiable,this tactic is taken from the Second World War where a Russian lieutenant was told by his colonel that he would be sent to the Russian front unless he did as asked. The colonel had the power, the lieutenant believed it was for real, and the result was predictable. He would do whatever was asked willingly, rather than being sent to the Russian front. In negotiation, it is referred to when providing two options. This is based on getting the other party to accept the better of two evils. One you know will prove challenging and the other an outright disaster. If the whole concept is not rejected, the chances are you will be seduced into agreeing to the challenging one. "PERSONAL FAVOR" This tactic attempts to make the position or request “personal” and works most effectively in familiar relationships: “You can do this for old times’ sake,” or “If you do this for me I will ensure your proposal is accepted,” or “You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.” It leans on a sense of obligation to the point where it’s aimed at leaving you feeling embarrassed if you do not yield. You must remain firm, point out the compromising position this would leave you in and explain that it’s not personal, just business. "GUILTY PARTY" This involves suggesting that the other party is breaking some code or agreement, or that they are going against the industry norm, or that a commitment has not been met or a performance not as it should be. This tactic is used to full effect where one party is negotiating compensation to include inconvenience, loss of face, indirect loss of earnings, even future risk; this results in a demand way beyond the normal fi nancial obligations. "THE SOCIAL SMELL" The social smell is used to imply that you are the odd one out. It’s designed to make you question your own judgment: “If everyone else is behaving in a certain way (agreeing), why am I not?” It comes in the form of a statement about what “others are doing” and importantly what you are not. It implies that you are out of sync, the odd one out, and that you are missing out or even being irrational. “Everyone else has committed … you’ll be the only one not included so you are likely to miss out whilst your competitors have all agreed.” The idea is that it helps apply pressure to conform, highlights isolation, and promotes self-doubt. "SILENCE" As a powerful tactic, silence is used to unnerve the other party. It can result in a waiting game because the first to talk is likely to be the first to concede. For many, the discomfort alone of continued silence can result in a concession or offer of further flexibility. And yet for the experienced negotiator it may be that they simply need time to think through their next move. Silence is best used directly after you have stated your proposal or after they have stated theirs. Just wait. Even if they respond, wait further. The pressure builds and often leads to more concessions. 4. Anchoring This is where one party sets out to form an anchor (an opening position taken up by one party from which they will move but such movement will come at a price). The aim of anchoring is to adjust the expectations of the other party providing an extreme and yet realistic opening position. Movement becomes relative to the anchor. If you open with your position first and are able to get the other party talking about it, even if this means them rejecting it, it is your position that becomes anchored in their mind. Unless they make a counter-offer. Often they become so preoccupied with attacking your position, they forget all about their own position. "SOW THE SEED EARLY" This can take the form of the advance telephone call, which is designed to introduce an idea or a position, allowing for any emotional reaction to take place prior to the meeting. Or ideas that are introduced and parked in earlier meetings in the knowledge that they will need to be addressed in subsequent meetings. Sowing the seed early is based on getting inside their heads and adjusting their expectations. "THE POWER STATEMENT" Opening statements are designed to manage the aspirations of the other party. They are usually used as a statement in the form of an assumed fact. The idea is to test an assumed position of power by effectively telling them that, whilst you are in a position of “indifference,” they are under pressure to conclude the deal with you: “I understand that you need an agreement in place by the end of the day,” or “I want to make it clear that today’s discussions are to ensure that we have given you every opportunity to win the business.” The language is that used by a “critical parent” by implying assumed authority designed to get the other party talking and thinking about how they are going to move towards you. "THE MOCK SHOCK" This is an extension to the power statement where you start the meeting by implying that all is lost: “We have decided that given your current performance levels and clearly no desire to offer compensation, terminating the contract is the only option for us.” Or, “This may only be a small order, but failure to agree could affect all of your business with us.” The devastating consequences of non-cooperation can shock the other party into reconsidering their position or backtracking from the outset, where saving the relationship becomes their primary objective. "THE PROFESSIONAL FLINCH" This is a shock reaction to their opening position. Both physically whether by extreme facial reaction and/or verbally, you are demonstrating your shock and surprise at their position. Used regardless of their opening offer and designed to lower their aspirations, the professional flinch has the effect of undermining their confidence in their position and expectations. "THE BROKEN RECORD" One party repeats their position. The more they repeat it, the more credible it becomes. The more their position is discussed, the more likely the discussion will revolve around their position. They start to sound like a broken record but the message gets through. Of course this can be interpreted as intransigence and can result in you losing patience and concluding the meeting. They will require a moderate amount of power of around 4/10 to be able to carry it off. 5. Empowerment This involves the degree to which you are authorized to trade and the extent to which others need to be involved in the decision-making process. "HIGHER AUTHORITY" The use of the boss or a mysterious and distant overseeing body required to sign off anything beyond those limits that you are allowed to trade. The idea is to convince the other party to agree within the level you are authorized to go to, so that they can complete the deal today, rather than risk the deal being jeopardized, or so as not to allow your boss to see the other concessions that you have already offered. It’s also used to disassociate yourself from not being able to accept a proposal: "That’s out of my control and I will need to come back to you on that one." "DEFENSE IN DEPTH" This is where several layers of decision-making authority allow for further conditions to be applied each time the agreement is referred. Typically it’s where your supplier or customer states that they will take the deal for sign-off to their boss. A day later, the call comes that, subject to one final concession, the deal will be agreed. You reluctantly agree. A day later, they call and state that their boss has signed it off and it’s now been sent for approval to the board and that if you could just agree to the 30-day payment terms it will gain agreement. Reluctantly you agree and ask if they will let you know when it has been approved. The next day they calls to again advise you that the board have now signed it off and they have now handed it over to Health and Safety for final approval and then advise you of yet another small concession that will be necessary if “final” sign-off is to be achieved. You should always understand the decision-making levels and process, otherwise you leave yourself exposed to defense in depth. "USE OF OFFICIAL AUTHORITY" This is used where one party disempowers themselves, saying that they cannot or are not allowed to change the terms. They refer to their own company policy, legal requirements, association requirements, or even historical precedents and, although sometimes true, it’s often a tactic in play used to legitimize their position. “Our company policy is 60 days payment on all transactions and there is nothing we can do about that.” It’s frequently used to provide rationale in an attempt to bolster the credibility of their proposal. Ensure you insist that such constraints are their problem and that you welcome suggestions on how they plan to work around them in order to avoid you having to escalate the issue. "IT'S ALL I CAN AFFORD" This is used to suggest that budgets are finite, the specification is fixed, and that it’s all that is available: “I have no other funds available so take it or leave it.” It’s designed to place the onus of obligation on the other party, implying that they need to work within that which you can afford. In contrast, when faced with such tactics the receiving party can change the specification, the volume, the timing, or any variable that helps to naturalize the implications of the fixed fee. "ONUS TRANSFER" Transferring the obligation for solutions or ideas onto the other party, to make it their problem. “We have a problem in making our payment on time this month. We can make the transfer but it is going to be 5 days late, how do you want to deal with this?” Once they have been advised, the problem becomes a shared one. The implications may still sit squarely with you but you have transferred the onus onto the other party. "OFF-LIMITS" This is where issues are positioned as off-limits (non-negotiable or “off the agenda” for the purpose of these discussions). They are often described as “things I can’t agree, so let’s focus on the terms we can agree today.” Remember, nothing is agreed until everything is agreed. Their motive is to protect some of the more critical issues from negotiation. This can also result in a negotiation over what is negotiable before the real negotiation even begins. This tactic is commonly used in political negotiations but regularly features in all types of commercial settlement negotiations too. "NEW FACES" When a new person takes over the relationship or a new account manager is introduced, both past precedents and history carry far less relevance. New faces need not be tied to or constrained by what has happened in the past. They can sometimes offer a solution to deadlock where personalities stand in the way of progress. They can provide for a fresh examination of affairs or can even be used to intimidate the other party where the seniority of the new negotiator carries certain gravitas. Retailers are renowned for changing their buyers systematically and periodically so that new faces remove the familiarity of an existing trading relationship. This keeps the focus on terms fresh and removes any scope for complacency. 6. Moving the costs around This category comes from reconfiguring the package or specification, or manipulating the terms in order to provide a different complexion to the deal. The relationship between specification and price is used by many tactical negotiators as a means of manipulating the cost of supply, whilst attracting the best possible price. "THE BUILDING BLOCK TECHNIQUE" This is where one party requests a price but only for part of their actual requirements. You then request prices for various quantity arrangements, ranging up to and including your actual needs. The idea is to manage expectations in the fi rst instance and understand the relative cost/price differences and implications across the different arrangements. This can reveal much about their cost base and margin structure. You then negotiate for a 1-year agreement, for example, in the knowledge that you can raise this to a 3-year agreement. You then seek incentives from the other party in the event that you could extend the agreement to 2 years, and then negotiate incremental terms for this “doubling” of the contract. Finally, you broaden the discussion to a 3-year partnership. Of course, to agree to such a deal, you will require more preferential terms. The building block technique involves planning out your stages, which can apply to any variable and provides time for the other party to adjust to concessions that would otherwise be difficult to extract. "WIPE THEIR PROPOSAL OFF THE TABLE WITHOUT SAYING NO" Each time they make a proposal, you say “yes, subject to our terms.” Your terms turn out to be either equally as outrageous, or are financially designed to offset the implications of agreeing to them. One party says: “Your discount levels based on last year’s performance are being adjusted from 10% to 7.5% for the year ahead.” And the other party responds: “Subject to you improving your promotional funding from $100,000 to $250,000 for the year, we will accept the reduction in discount.” The response from the fi rst party will inevitably be: “We can’t do that” to which you suggest: “and that’s why we are not in a position to accept your position.” You rarely need say no in a negotiation. Just fi nd a way, a basis, a set of conditions upon which the consequences, be they fi nancial, risk, or third-party implications, are neutralized by the terms you attach to it. "LINKING THE ISSUES" Everything is conditional and therefore linked to other conditions. Linking the relative values and importance of issues is key to ensuring that linked issues gain the attention you require. This is sometimes used to protect certain terms. For example, if the contract length was very important to one party and they knew that a high-value variable to the other party was attracting a 10,000-volume order, the two would be linked to ensure that the contract length issues could not be easily dismissed. "SIDE ISSUE OR RED HERRING" This is where some issues are introduced onto the agenda that have been positioned to lose or trade off against. Later during the negotiation, value is traded as each of the red herrings is conceded, having played their part in attracting improved terms elsewhere. For example, you need to attract shorter lead times and improved discounts. Both items are on the agenda as is a new termination clause, allowing you to terminate the contract with very short notice and lower volume discount thresholds. The last two are effectively red herrings, which you expect to concede on. However, in doing so you are able to trade for better terms on lead times and discounts. "THE SLICE" This is where you believe that the issue is of high value to the other party and trade against the issue in “slices.” For example, you know that volume is critical to them. You are currently at 50,000 units and know that your requirement is for an order of 150,000 units. Rather than trade up to 150,000 units, you trade to 80,000 in return for a concession. Later you trade to 100,000 for a further concession, then to 115,000, and so on. Each move is conditional on a concession, ensuring that the value of your total move is maximized. 7. Deceit There is no other way to describe this fi nal category: deceit. If reputation or relationships hold any value to you or your business, think twice before using the following. More importantly, be wary of those who carry a different view and choose to use deceit – they may choose to use it on you even after the contract has been signed. "TROJAN HORSE" This is named after a tactic used during the ancient war on Troy, which led to the saying: “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.” The Greeks left a gift in the form of a wooden horse outside Troy. The Trojans accepted the gift and brought it inside the city only to find that thehorse was full of soldiers ready to invade. Beware if the deal appears too good to be true. This relates to the hidden small print, and the conditions and issues that can literallycome out of the woodwork after the deal has been completed. The Trojan horse represents a package created to entice you. Once accepted, it has some surprises in store because much of the downside was hidden at the time of agreement. "THE INCORRECT SUMMARY" This is where one party summarizes from their perspective, leaving out or even adjusting some of the terms discussed earlier. The idea is that you won’t notice or won’t challenge through fear of jeopardizing progress. Try to ensure that you summarize progress throughout the meeting and that you do so from your perspective. Also, ensure that you summarize in writing after the meeting. If you don’t agree on what you believe you have agreed, then you’re unlikely to have an agreement that is going to stand the test of time. "DELIBERATE MISUNDERSTANDING" So as to open up areas that have already been regarded as concluded, one party introduces a condition that they know to be unacceptable. After you have responded with confusion or start to demand clarity they adopt an “innocent misunderstanding” stance. Their motives could be varied, but it is usually related to stalling progress or allowing them to try and renegotiate terms that have otherwise been regarded as closed. "THE DUMB FOREIGNER" They choose not to understand you at a given time during the negotiation due to language difficulty. This is especially used once the subject of price is introduced. As they seek to take up a firm position, they appear increasingly confused by what you have to say as you attempt to explain your position. When faced with such behavior, patience, restating your position, and maybe even a “time out” is needed to dampen their confidence. "THE LOSS LEADER" This involves one party convincing the other to agree to a deal at highly preferential rates, which will lead to benefits in the future. These “benefits” are often not contractual, conditional, or delivered on. In fact they are often used as a precedent: “You were able to offer that price last time we worked with you so we know you can do it again.” If you are to enter into such agreements always ensure that it is in writing and the conditions are clearly stated in the contract. KEY TAKEAWAYS Influential tactics in negotiation have been used for thousands of years as a means of gaining leverage and advantage. They can be as subtle as providing misleading information or as blatant as an outright lie. As you never need to lie in negotiation, many tactics are regarded as a fast route to destroying trust. • Recognize tactics being used and qualify them by challenging their consequences. • The type of the tactics you use should be limited to how much trust and dependency you require in the relationship once the deal is done. • The risk/benefit of employing tactics is something you must judge based on your own circumstances, objectives, motivation, and values. • More than one tactic at a time will often be combined to increase pressure as others will seek to manipulate your actions. • Performing as a conscious competent negotiator will help increase your awareness of the tactics in play and will help you recognize, qualify, challenge, and navigate through the gamesmanship.

Pages

- Index of Lessons in Technology

- Index of Book Summaries

- Index of Book Lists And Downloads

- Index For Job Interviews Preparation

- Index of "Algorithms: Design and Analysis"

- Python Course (Index)

- Data Analytics Course (Index)

- Index of Machine Learning

- Postings Index

- Index of BITS WILP Exam Papers and Content

- Lessons in Investing

- Index of Math Lessons

- Index of Management Lessons

- Book Requests

- Index of English Lessons

- Index of Medicines

- Index of Quizzes (Educational)

Thursday, March 5, 2020

Tactics and Values in Negotiation (The Negotiation Book by Steve Gates)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment